Human Monkeypox infection: what we know so far

Abstract

Human monkeypox infection is a zoonotic disease caused by a double-stranded DNA virus and endemic in Africa. Cases outside of Africa were uncommon and usually associated with travel to west Africa. Recently, outbreaks have been reported in non-endemic countries without an identifiable epidemiological link. This had led to global concern and WHO declared human monkeypox infection as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in July 2022. It usually presents with fever and a rash similar to chickenpox or syphilis. Currently, there are two vaccines effective against monkeypox, namely, JYNNEOS and ACAM2000. Though it is self-limiting and not very transmissible, contact tracing, early detection of cases and isolation/quarantine to prevent further spread is essential to control the outbreaks.

Keywords: monkeypox; human monkeypox; orthopoxvirus.

Introduction

Moneypox is a zoonotic disease caused by a virus that belongs to Orthopoxvirus genus, Chordopoxvirinae subfamily of the Poxviridae family, which is closely related to variola virus (smallpox). It was first discovered in monkeys in a Danish laboratory in 19581. However, it was in 1970 when the first case of human monkeypox infection was reported in a 9-month-old boy of the democratic republic of Congo in Central Africa2. Since then, it has spread to other countries but mainly confined to central and Western Africa. Based on their geographic distribution, two genetic types of monkeypox virus were identified: the central African or Congo type and the West African type3. Both cause a similar clinical syndrome; however, Central African variant is reported to be more transmissible and have three times higher mortality4.

The first reported monkeypox case outside of Africa was in 2003 in a 3-year-old girl in Texas, USA. Monkeypox-infected rodents from Ghana arrived through shipment to USA, which were kept near the prairie dogs. The dogs in turn contracted the virus and the girl was bitten by her pet prairie dog. Several other Americans were subsequently diagnosed with monkeypox infection with a total of 47 confirmed or probable cases during this outbreak5.

Since early May 2022, outbreak of monkeypox has been reported in non-endemic countries, with the first cases documented in the United Kingdom, followed by other countries of Western Europe, North and South America, the Middle East, North Africa, and Australia. As of 22 September 2022, there are a total of 64,916 confirmed cases in more than 70 countries with 64,336 (99%) cases in locations that have not historically reported monkeypox6. Due to the emerging cases in non-endemic countries, on July 23, 2022, World Health Organization (WHO) declared the current monkeypox outbreak as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC)7. Europe is the epicentre of recent escalating outbreak, with 25 countries reporting more than 1,500 cases, or 85% of the total worldwide. Monkeypox is classified as a High Consequence Infectious Disease (HCID) in the UK8.

Pathogenesis

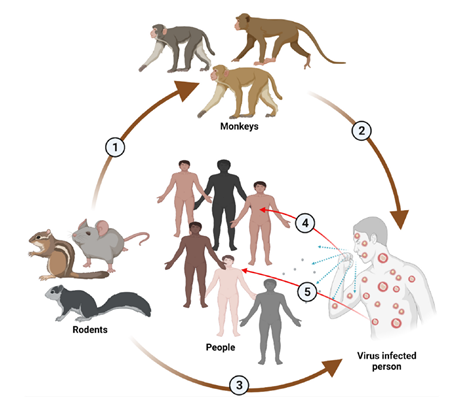

The specific animal host reservoir and mode of transmission of monkeypox remain unknown. Rodents are the largest animal reservoirs of the virus though it is detected in diverse animal species such as squirrels (rope and tree), striped mice, rats, dormice, and monkeys9.

MPV transmission10

1. From rodents to monkeys. 2. From monkeys to human. 3. From rodents to humans.4. From infected person to healthy people through cough droplets. 5. From infected person to healthy people through direct skin contact

Recent outbreaks were reported primarily among men who have sex with men (MSM) which suggests transmission through close and intimate physical contact. Human to human transmission is through contact with infected skin, respiratory droplets, oral secretions, body fluids or fomites. Presence of virus in the seminal fluid is suggestive of sexual transmission and recent cases were mainly reported among MSM. It can also be transmitted from infected mother to foetus leading to congenital infection11.

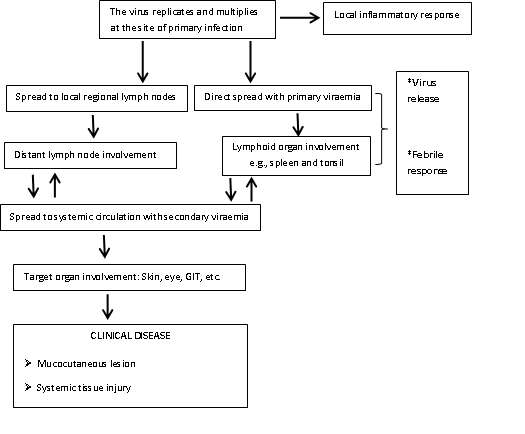

The virus then rapidly replicates at the inoculation site and later spreads to adjacent lymph nodes. Replication occurs within the cytoplasm of infected cells rather than in the nucleus, unlike many DNA viruses, as they can produce the proteins required for both transcription and replication.

Fig 1: Pathogenesis of monkeypox virus infection in humans

Clinical manifestations

People living in forested areas, male sex, children younger than 15 years, and absence of smallpox vaccination are at increased risk of monkeypox. It was reported to be 5.2 times lower in those vaccinated against smallpox than unvaccinated individuals (0.78 versus 4.05 per 10,000)12.

Being a viral illness, monkeypox is usually self-limiting with symptoms lasting from 2 to 4 weeks. However, severe cases can occur with reported case fatality ratio of around 3–6%13. It has an incubation period of 7 to 17 days, followed by initial febrile prodromal period of 1 to 4 days, and a rash period of 14‐28 days14.

Monkeypox infection presents with an initial prodromal phase of fever, chills, headache, backache, muscle aches, fatigue and lymphadenopathy which is followed by the appearance of generalised well‐circumscribed skin rashes typically in a centrifugal pattern. Lesions often start on the face then spreads to other parts of the body, including palms and soles. Skin lesions will go through different stages such as macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, umbilicated pustules, and finally form a scab that eventually falls off. These lesions also involve the genital area in cases among MSM15.

Stages of monkeypox skin rash

1. Macules/papules

2. Vesicles

3. Pustules

4. Umbilicated pustules

Pustular stage is often associated with second febrile period and deterioration of patient. A more severe disease is likely to occur in vulnerable populations such as children, elderly, pregnant mothers, and immunocompromised individuals. High viraemia and death can result in severe disease following direct human-to-human transmission even without sustained infection7.

Complications

Documented complications of monkeypox include encephalitis, pneumonitis, secondary bacterial infection, septicaemia, shock secondary to diarrhoea or vomiting, sight-threatening keratitis, corneal scarring resulting in permanent blindness, and pitted scarring of the skin. Since smallpox vaccination was approximately 85% protective against monkeypox, severe complications are observed among the unvaccinated (74%) than the vaccinated (39.5%)16.

Differential diagnoses

The main differential diagnosis is chickenpox, however, the lesions in chickenpox are more superficial and evolve in different stages whereas in monkeypox the lesions evolve uniformly to become vesicles. Moreover, chickenpox has denser lesions on the trunk than on the face and extremities. Enlarged lymph nodes, especially submandibular, submental, cervical, and inguinal nodes differentiate monkeypox from chickenpox or smallpox17.

Other differential diagnoses include molluscum contagiosum, rickettsial infections, measles, bacterial skin infections (Staphylococcus aureus), scabies, syphilis, anthrax, drug reactions, and other non-infectious causes of skin rash9.

Investigations

The diagnosis of human monkeypox is mainly clinical, with high index of suspicion and typical skin rashes. For definitive diagnosis immunohistochemistry for viral antigen detection, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay for antibodies detection (IgG and IgM), viral isolation and culture, and specific viral DNA detection using polymerase chain reaction are required14. Viral DNA can be detected by PCR in the skin lesions, upper respiratory tract swabs, blood, or urine8. Two-stage testing is usually performed with initial pan-orthopox polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by a specific monkeypox PCR test18.

Treatment

At present, there are no licensed treatments for human monkeypox. Symptomatic management, supportive care, and treatment of secondary bacterial infections remain the main options. Two oral medications, brincidofovir and tecovirimat, that have been approved for smallpox infection also demonstrated efficacy against monkeypox inanimals19,20. Brincidofovir inhibits the viral DNA polymerase21 whereas Tecovirimat inhibits the viral envelope protein VP37, which blocks the final stages in maturation and release of virus from the infected cell, thus inhibiting the spread22. However, none of these drugs has been studied in human efficacy trials.

In an observational study of seven confirmed cases of human monkeypox infection in the UK, three received oral Brincidofovir 200 mg doses, one was given oral Tecovirimat 600 mg twice daily for 2 weeks and the other three were treated with supportive care only. Transient reduction in viral DNA was seen with brincidofovir, however, it was not consistent between patients. Moreover, all three patients developed deranged liver enzymes. Similarly, clinical and virological responses were reported to be more rapid in the one and only tecovirimat-treated patient than others. Nonetheless, the very small sample size limits the confidence in drawing a conclusion for the relation between Brincidofovir or Tecovirimat treatment and superior clinical outcomes or disease course8.

Majority of monkeypox cases are mild and self-limiting even without specific therapy, however, the prognosis of the disease depends on prior smallpox vaccination status, comorbidities, or concomitant illnesses23.

Prevention

Measures to prevent the spread of infection in endemic regions include limiting direct exposure to blood and inadequately cooked meat as well as avoiding contact with rodents and primates. Health education on proper handling of animal reservoir species is vital. Infection control measures including standard, contact, and droplet precautions are important to prevent human-to-human transmission. Suspected cases should be placed in a negative air pressure isolation room, or a private room if there are no such facilities.

Smallpox vaccine is shown to be protective against monkeypox, thus, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends smallpox vaccination within two weeks following unprotected exposure to a confirmed human case or a diseased animal. According to 2018 CDC recommendations, pre exposure smallpox vaccination is given to contacts of monkeypox patients, health care workers caring for patients and their contacts, veterinarians, field investigators, animal control personnel and researchers24.

On August 9, 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an emergency use authorization (EUA) for JYNNEOS vaccine for prevention of smallpox and monkeypox. It is given as an intradermal or subcutaneous injection to individuals 18 years of age and older who are at high risk for monkeypox infection. It is the primary vaccine used during the current outbreak in the United States which is given in two doses four weeks (28 days) apart25.

An alternative is ACAM2000 vaccine which has been approved by FDA since August 2007 for protection against smallpox. It is now made available for use against monkeypox under an Expanded Access Investigational New Drug (EA-IND) protocol. It is administered subcutaneously as a single dose using a special stainless steel bifurcated needle to those aged one year and above. Contraindications of this vaccine include pregnancy, breastfeeding, immunocompromised conditions, severe allergic reaction after a previous dose or components of the vaccine, and infants less than one year old. Individuals are considered vaccinated against monkeypox 28 days after getting the single vaccine dose26.

Future directions

There are unanswered questions such as (1) why the resurgence now (2) how this new outbreak chain started in Europe (3) why it is more commonly seen in MSM (4) why the clinical presentation is milder. Therefore, it is difficult to predict the future of current monkey pox outbreaks. However, as this virus is not very prone to mutations and less transmissible, along with the availability of effective vaccines, the current outbreak is likely to be controlled18. Nevertheless, there remains the risk of recurrence. Thus, active participation and co-operation of all parties is of utmost importance. In addition, prolonged upper respiratory tract viral shedding even after resolution of skin lesions is a significant challenge in prevention and control measures8. Therefore, education and awareness amongst healthcare professionals and communities as well as development of monkeypox vaccination guidelines is crucial.

References

- Magnus P, Andersen EK, Petersen KB, Birch-Andersen A.(1959).‘A pox-like disease in cynomolgus monkeys’,ActaPathologica et MicrobiologicaScandinavica, 46(2), pp. 156-176.

- Ladnyj ID, Ziegler P, Kima E. (1972). ‘A human infection caused by monkeypox virus in Basankusu Territory, Democratic Republic of the Congo’,Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 46(5), pp.593‐597.

- Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, Lienert F, Weidenthaler H, Baer LR, et al. (2022).‘The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox-A potential threat? A systematic review’,PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 16(2), e0010141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141

- Chen N, Li G, Liszewski MK, Atkinson JP, Jahrling PB, Feng Z, et al. (2005).‘Virulence differences between monkeypox virus isolates from West Africa and the Congo basin’,Virology, 340(1), pp.46-63.

- Burki, T.(2022). ‘Investigating monkeypox’,The Lancet, 399(10343), pp.2254 – 2255.

- CDC 2022 Monkeypox Outbreak Global Map https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html(Accessed on 23.9.2022)

- Nuzzo JB, Borio LL, Gostin LO. (2022). ‘The WHO Declaration of Monkeypox as a Global Public Health Emergency’,JAMA, 328(7), pp.615–617.

- Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, Snell LB, Wong W, Houlihan CF, et al. (2022). ‘Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK’,The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 22(8), pp.1153-1162.

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, Asogun D, Yinka-Ogunleye A, Ihekweazu C, et al. (2019). ‘Human Monkeypox: Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics, Diagnosis, and Prevention’,Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 33(4), pp.1027-1043.

- Kumar N, Acharya A, Gendelman HE, Byrareddy SN. (2022). ‘The 2022 outbreak and the pathobiology of the monkeypox virus’,Journal of Autoimmunity, 131,102855.

- Kannan S, Shaik SAP, Sheeza A. (2022). ‘Monkeypox: epidemiology, mode of transmission, clinical features, genetic clades and molecular properties’, European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 26(16), pp.5983-5990.

- Rimoin AW, Kisalu N, Kebela-Ilunga B. (2007). ‘Endemic human monkeypox, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2001-2004’,Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13, pp.934–937.

- Monkeypox. WHO key facts.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/monkeypox (Accessed on 24.9.2022) - Kabuga AI, El Zowalaty ME. (2019). ‘A review of the monkeypox virus and a recent outbreak of skin rash disease in Nigeria’,Journal of Medical Virology, 91(4), pp.533-540.

- Mahase E. (2022). ‘Monkeypox: What do we know about the outbreaks in Europe and North America?’,BMJ, 377,o1274.

- Fine PE, Jezek Z, Grab B, Dixon H. (1988). ‘The transmission potential of monkeypox virus in human populations’,International Journal of Epidemiology, 17(3), pp.643–650.

- Osadebe L, Hughes CM, ShongoLushima R. (2017). ‘Enhancing case definitions for surveillance of human monkeypox in the Democratic Republic of Congo’,PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 11:e0005857.

- P. Simoes, S. Bhagani. (2022). ‘A viewpoint: The 2022 monkeypox outbreak 2022’, Journal of Virus Eradication, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jve.2022.100078.

- Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA. (2018). ‘Oral tecovirimat for the treatment of smallpox’,The New England Journal of Medicine, 379, pp.44–53.

- Chittick G, Morrison M, Brundage T, Nichols WG. (2017). ‘Short-term clinical safety profile of brincidofovir: a favorable benefit-risk proposition in the treatment of smallpox’,Antiviral Research, 143, pp.269–277.

- Lanier R, Trost L, Tippin T. (2010). ‘Development of CMX001 for the treatment of poxvirus infections. Viruses’, https://doi. org/10.3390/v2122740.

- Russo AT, Grosenbach DW, Chinsangaram J. (2021). ‘An overview of tecovirimat for smallpox treatment and expanded anti-orthopoxvirus applications’,Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy, https:// doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2020.1819791.

- Rizk JG, Lippi G, Henry BM, Forthal DN, Rizk Y. (2022). ‘Prevention and Treatment of Monkeypox’,Drugs, 82(9), pp.957-963.

- CDC. (2018). ‘Monkeypox’,MMWR Morbidityand Mortality Weekly Report, 67, pp.306–310.

- Monkeypox Update: FDA Authorizes Emergency Use of JYNNEOS Vaccine to Increase Vaccine Supply. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/monkeypox-update-fda-authorizes-emergency-use-jynneos-vaccine-increase-vaccine-supply

- ACAM2000Vaccine.https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/vaccines/acam2000.html

Author Information

Han Ni1

1. Associate Professor (Clinical)

Newcastle University Medicine Malaysia