Mystery of Cushing

A 28 year-old monk from Bago, previously healthy, was referred to the Endocrinology Department, Yangon General Hospital for puffiness of face, oedema of lower limbs and acneiform eruption on face, chest and back for 2 month’s duration. There was also increased facial hair growth, fatigue, tiredness and inability to walk for some distance due to weakness of lower limbs. The patient and family members also noticed high blood pressure (BP) and changes in appearance. He denied taking any medications. The patient had no history of other diseases. Family history was uneventful.

On physical examination, the patient had Cushingoid face (moon face and hirsutism) with acneiform eruption on face, chest and back with thin skin and purple striae on the lower abdomen and inner aspect of thigh. High BP of 160/110 mmHg with pulse rate of 88 per minute was also noted. There were no other abnormalities examined.

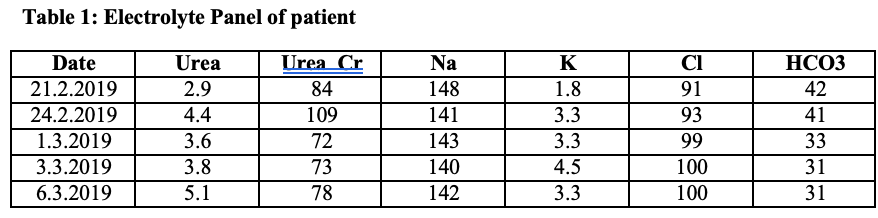

On investigation workup, persistent hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis was found as shown in the following table. The 24-hour urinary potassium was 95 mmol/day that was within normal range (25-125 mmol/day).

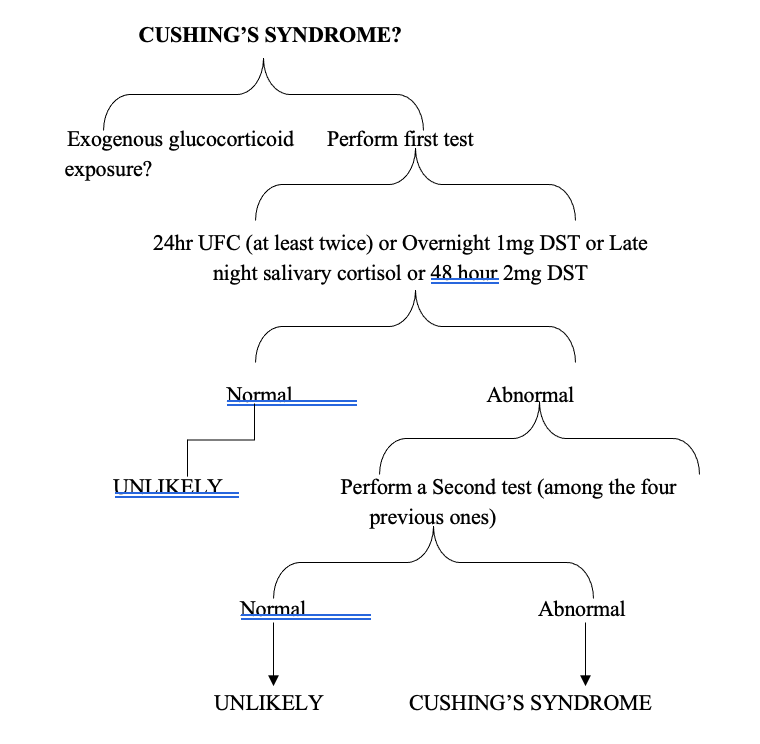

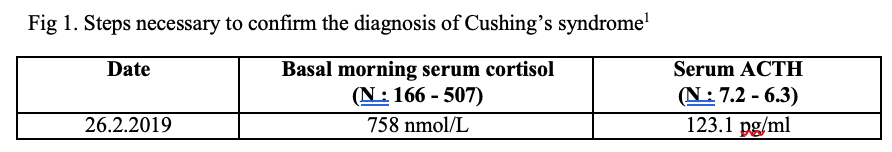

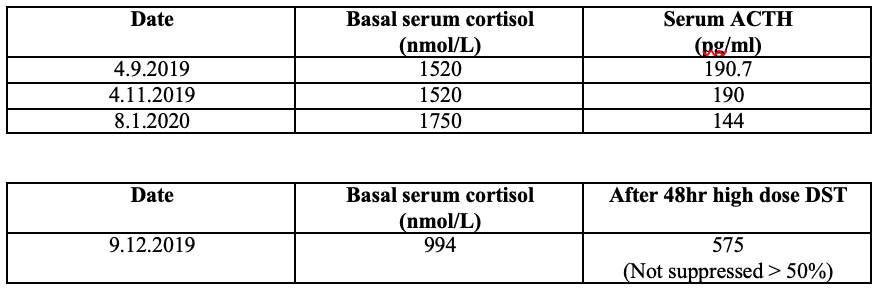

Although this case had given the impression of secondary hypertension due to either Conn’s syndrome or Cushing’s syndrome, the attending endocrinologists decided to skip screening test for Conn’s syndrome because of obvious Cushingoid features. To proceed for workup of the Cushing’s syndrome as the flow diagram (Figure 1), the patient was assessed for early morning basal serum cortisol and ACTH to exclude exogenous source of glucocorticoids.

The results excluded exogenous source of glucocorticoids and pointed to endogenous hypercortisolism. To confirm endogenous hypercortisolism, the screening tests including 24-hour urinary cortisol and 1mg overnight dexamethasome suppression test (OVDST) were performed. The results of non-suppressed serum cortisol in OVDST in the expense of normal 24 hours urinary cortisol indicated Cushing’s syndrome. (Limitation was that the locally available test was 24-hour urinary cortisol, not urinary free cortisol).

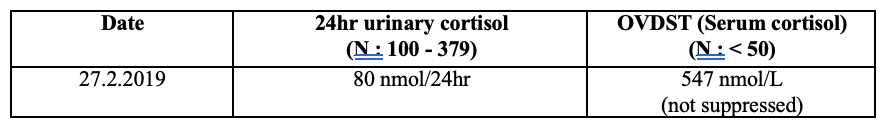

The next step was to determine the source of endogenous hypercortisolism. Since the basal ACTH was 123.1 pg/ml (>10 pg/ml), the source might be ACTH-dependent hypercortisolism. The steps for processing of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome were shown in the flow diagram (Figure 2).

Fig 2. Steps necessary for the etiological diagnosis of ACTH dependent Cushing’s syndrome1

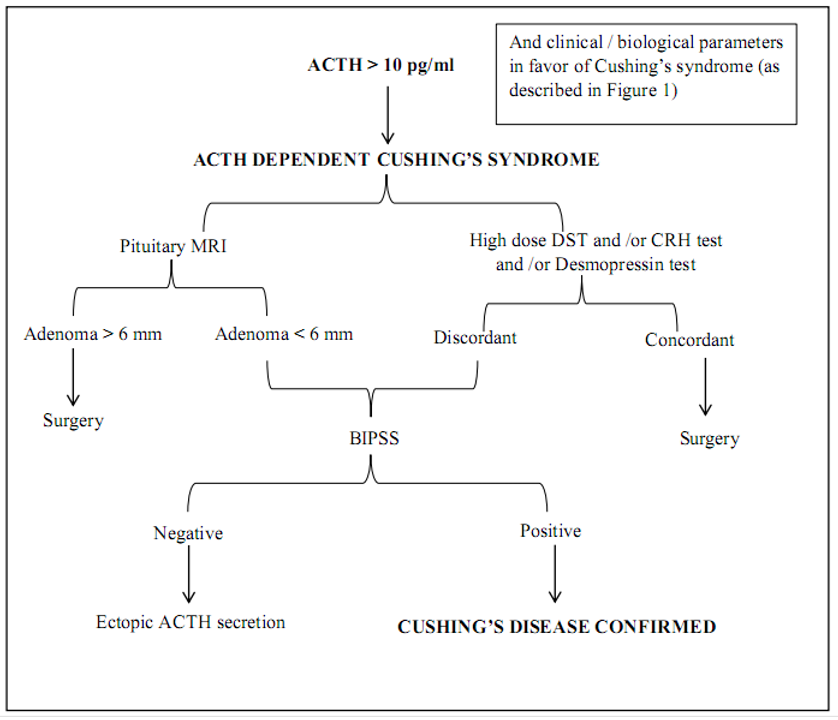

Since there was limitation to do CRH stimulation test and Desmopressin test, only HDDST was done and serum cortisol was not suppressed more than 50 % of basal serum cortisol.

In case of ACTH-dependent endogenous hypercortisolism, the pretest probability for pituitary origin is > 80% overall and hence, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary region is the next step. Although suppression is absent in patients with Cushing’ syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion or adrenal abnormalities, MRI (brain) was performed showing tiny signal changes (3.2 x 4.2 x 12mm) noted at right side of anterior part of pituitary fossa which showed delayed enhancement with no hemorrhage and no cavernous sinus invasion suggestive of pituitary microadenoma. This MRI result misled to discussion with neurosurgeons for possible surgery. The neurosurgeons declined the surgery since the tumor was a microadenoma with no compression.

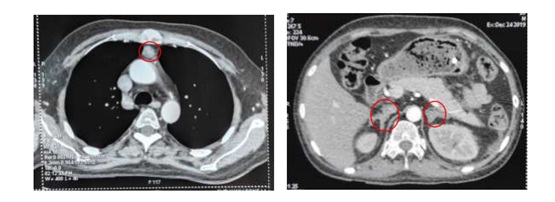

To locate ectopic source of ACTH, CECT (chest, abdomen and pelvis) was also done5 and the scans showed chest infection with bronchiectatic changes,? slight contrast enhancing lesion in thymus area and no adrenal glands enlargement.

Since there was no clear focus except thymus area in the scans, the patient was treated with Hebersser SR 100mg OD and Losar 50mg HS for high BP, Aldactone 25mg 2 OD and Slow K 2 BD for persistent hypokalemia and Ketoconazole 200mg TDS for hypercortisolism. In the meanwhile, the patient suffered alternating bowel habit off and on for 1month, together with lower abdominal pain, fever and loss of appetite but not bleeding per rectum. Therefore further investigations were done such as stool C&S, blood C&S, widal test, tumour markers and colonoscopy. Apart from mild colitis in colonoscopy, the results were normal.

Between September 2019 and January 2020, the patient had been still suffering progressive worsening of Cushingoid appearance, uncontrollable BP and persistent hypokalemia despite medical treatment and serial serum cortisol level was found to be progressively increased. To consider other possibilities, the endocrinologist team reviewed the case and was strongly suspicious of ectopic Cushing’s syndrome and then, consulted with senior radiologist with the first CT scan results. CECT (chest and abdomen) and HDDST were repeated. Serum cortisol was still failed to suppress in HDDST.

The second CECT stated features suggestive of thymoma (2.1 x 2.0 x 2.7 cm), most likely malignant thymoma (benign lesion is less likely), pulmonary nodule on posterobasal segment of left lower lobe (DDx: infective or metastatic nodule), left pleural effusion and bilateral diffuse adrenal enlargement suggestive of adrenal hyperplasia.

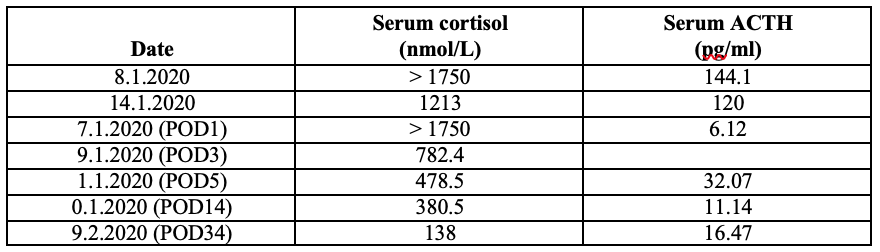

Finally, ectopic Cushing’s syndrome with thymoma was diagnosed and the patient was referred to Thoracic Surgical Unit, Yangon Specialty Hospital. Sternotomy & thymectomy was done on 16th January, 2020. Biopsy showed suggestive of neuroendocrine tumor (NET) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE), Synaptophysin and Chromogranin was returned back as positive.

After operation, serial serum cortisol and ACTH levels were become normal and serum potassium was also back to normal and stopped potassium replacement and Aldactone.

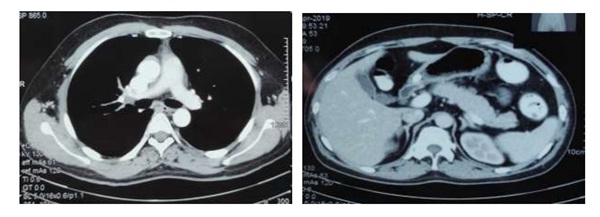

For thymus carcinoma (NET), oncologist suggested to give 6 cycles of chemotherapy with IV Dexamethasone, IV Etoposide and IV Cisplastin for 3 days per month. While he was taking chemotherapy, he felt normal. Cushingoid picture was disappeared 3 months after surgery and hypokalemia and hypertension were also resolved without medications. Recheck CECT (chest, abdomen and pelvis) after receiving 6 cycles of chemotherapy on 10th July, 2020 showed interval complete regression of primary tumor and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia.

The monk attended regular 6 months follow-up at Endocrine Clinic until 2022 and he was completely symptoms free and being well.

In this case, high clinical suspicion together with biochemical evidence of endogenous ACTH dependent hypercortisolism and complete resolution of Cushingoid features and normalization of biochemical evidence and radiological regression of primary thymus tumor and bilateral adrenal hyperplasia after thymectomy indicated that the final diagnosis was ectopic ACTH secreting Cushing’s syndrome due to NET of thymus gland.2,3,4

Conclusion: Conducting a series of tests for a typical Cushing’s syndrome case to prove endogenous hypercortisolism is not easy as described in literature in resource limited setting. Moreover, searching ectopic ACTH causes of Cushing’s syndrome is a mystery, and localizing an ectopic tumor source is an enormous task. At times, the source of ectopic Cushing’s syndrome remains occult and may reveal itself on follow-up. Hence, a stepwise approach for diagnosis is the golden rule and in case of doubt, a close follow-up of the case with a wait-and-watch policy is best.

From this case, important point to pick up is that the 50% non-suppressible serum cortisol in HDDST is more favor of ectopic Cushing’s syndrome despite the finding of a pituitary microadenoma which is a Red Herring. Suspicious mind should be kept until finding the culprit (eg; in this case, hypokalemia leads suspicious to search ectopic Cushing’s syndrome). Collaboration of clinical features, biochemical evidences and radiologist’s expert opinions achieve good outcome for this patient.

References

(1) Elamin, MB., Murad, MH., Mullan, R., Erickson, D., Harris, K. & Nadeem, S. (2008) Accuracy of diagnostic tests for Cushing’s syndrome a systematic review and metaanalyses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 93, 1553-62.

(2) Jennifer, L. Dixon., Sanket, P. Borgaonkar., Anupa, K. Patel., Scott, I. Reznik., W. Roy

Smythe. & Philip, A. Rascoe. (2013) Thymic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma Producing Ectopic Adrenocorticotropic Hormone and Cushing’s syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 96, E81-E83.

(3) Lawrence, L., Zhang, P. & Makin, V. (2019) A unique case of ectopic Cushing’s syndrome from a thymic neuroendocrine carcinoma. ID: 19-0002; DOI: 10.1530/EDM-19-0002.

(4) Neary, NM., Lopez-Chavez, A., Abel, BS., Boyce, AM., Schaub, N., Kwong, K., Stratakis, CA., Moran, CA., Giaccone, G. & Nieman, LK. (2012) Neuroendocrine ACTH-Producing Tumor of the Thymus-Experience with 12 Patients over 25 Years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 97, 2223-2230.

(5) Young, J., Haissaguerre, M., Viera-Pinto, O., Chabre, O., Baudin, E. & Tabarin, A. (2020) Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic ACTH secretion: an expert operational opinion. European Journal of Endocrinology. 182, R29-R58.

Author information

San Bo Bo1, Aung Moe Wint2, Chomar3

- Lecturer, Department of Endocrinology, University of Medicine 1, Yangon

- Professor and Head of Department of Endocrinology, University of Medicine 1, Yangon

- Associate Professor, Department of Endocrinology, University of Medicine 1, Yangon