Corrosive Injury Of Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

Introduction

Corrosive injury of upper GI tract still represents a major medical and surgical emergency worldwide. Eighty percent of corrosive injuries occur in children, where it is due to accidental ingestion. Adults usually ingest caustic agent with a suicidal intent. Occasionally, ingestion of caustic agents can be seen in psychiatric or alcoholic patients. Even in developed countries, most surgical unit will only encounter a small number of cases per year. The workup of these patients is poorly defined and no clear therapeutic guidelines are available. [1]

Case Presentation

A 62 year gentleman presented with gastric outlet obstruction for nearly one month. He has a history of ingestion of germ killing formula insecticide 150 ml ( HCl 15% W/W plus Ethoxylated Alcohol 2% W/W) one month ago with suicidal intent. First aid treatment was taken at a nearby clinic. Later, the patient consulted a renowned GI physician and took treatment.

1.Senior Consultant Surgeon, Department of General surgery, PunHlaing Siloam Hospitals

2. Senior Medical Officer, Department of General Surgery, PunHlaing Siloam Hospitals

3. Professor,Patron,Clinical Excellence, PunHlaing Siloam Hospitals

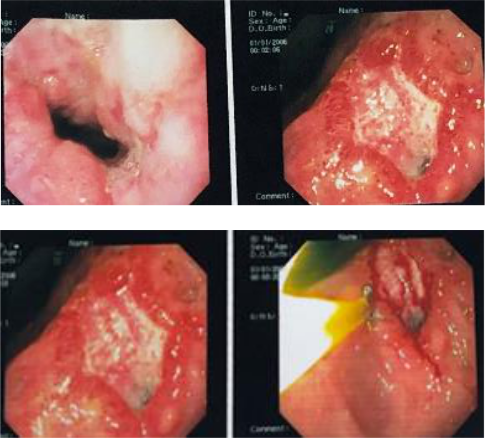

The first endoscopic examination was done by GI physician after two weeks of caustic ingestion. Endoscopy revealed food retention in the whole stomach with an ulcerative growth 3x 2cm noted at the pyloric antrum. Oesophagus showed no ulcer. Biopsy was taken from pyloric ulcer. Endoscopic diagnosis was CA pyloric antrum with gastric outlet obstruction. Reported biopsy was ulcerated poorly differentiated adeno carcinoma, pyloric antrum of stomach. Patient was then referred to surgeon.

Fig 1 . First time OGDS

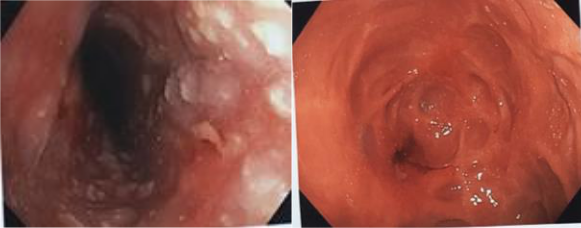

Fig 2. Second time oesophago gastro duodeno scopy (OGDS)

Second reassessment OGDS was done 5th week after event by surgeon and showed severe erosive oesophagitis of whole length. Fundus was normal but body of stomach revealed healed severe erosion with multiple dimpling. Pylorus was tightly stenosed with scar. Duodenum could not be assessed.

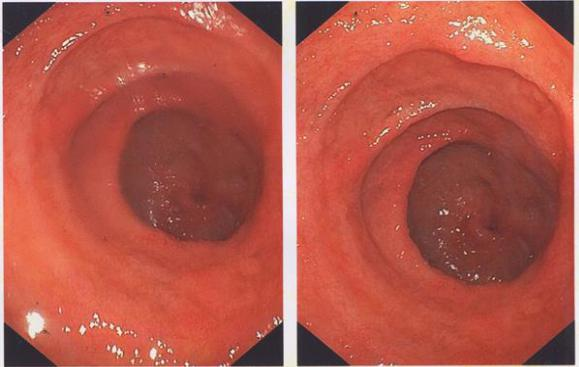

Fig.3. Intraoperative retrograde view of stenosed pylorus and duodenum

Patient was thin and emaciated. Baseline parameters were normal except for low total and differential protein. After correction of fluid and nutrition, surgery was planned. Intraoperative findings were marked scarring of pylorus without features of infiltration and dilated stomach. Simple gastro-jejunostomy was done. Postop period was uneventful and patient discharged on 7th post op day and soft diet advised.

On assessment at the regular post operative two weekly follow up, the patient has remarkable weight gain and could consume a normal diet. His mental status was normal and he was taking regular medication.

Literature Review

There are so many chemicals commonly available in modern households that can be ingested either inadvertently or intentionally. Failure to recognize the seriousness of the accident and to provide adequate therapy could result in serious morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate is between 10 to 20 % and rises to 78 % in case of suicidal attempt. The extent of injury depends on the type of agent, its concentration, quantity and physical state,duration of exposure and the present of food particles in the stomach.

Pathophysiology

The dichotomy of oesophageal versus gastric injury in cases of acid and alkali ingestion has long been recognized by surgeons and gastroenterologists. Whilst acid is said to “lick the oesophagus and bite the pyloric antrum”, alkali tends to cause a more uniformly severe mucosal injury to the oesophagus. Although acid injury is usually limited to the stomach, 6%-20% of patients have other associated oesophageal and small intestinal injuries. Acid injuries cause “coagulation necrosis” on tissue contact; the coagulum formed hinders any further tissue penetration. On the other hand, caustic injuries induce “liquefaction necrosis”, a process that leads to the dissolution of protein and collagen, saponification of fats, dehydration of tissues and thrombosis of blood vessels, resulting in deeper tissue injury. [2]

Zargar, et al noted that acute gastric injury was present in 85.4% of their patients who had ingested acid, involving mainly the distal half of the stomach with 44.4% having late complications in the form of pyloric or antral stenosis and linitis plastica-like deformity. The relative sparing of the duodenum is thought to be due to pyloric spasm induced by the irritant acid in the antrum and the alkaline pH of the duodenum.

Symptoms and Signs

Acute corrosive injuries lead to severe pain of the lips, mouth, and throat. Hoarseness, stridor, and respiratory distress indicate airway injury. Dysphagia, odynophagia, and drooling suggest oesophageal injury. Abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting are indicative of stomach injury. Varying degrees of hematemesis occur due to mucosal injury, but massive hematemesis is generally due to aortoesophageal fistula. Severe retrosternal and upper back pain suggests oesophageal perforation.[8,9] Severe abdominal pain with guarding and rigidity of the abdomen with rebound tenderness denotes gastric perforation.[10-12] The early signs and symptoms may not correlate with severity of tissue injury.

Investigations

Leukocytosis and raised C-reactive protein indicates a severe acute inflammatory response to caustic injury. Arterial blood gas analysis alteration occurs with airway involvement. Severe electrolyte imbalance seen due to large amount of fluid loss in the third space. Coagulation profile is important in bleeding patients. Altered renal and liver functions occur in response to hypotension and systemic infection.

Good chest X-ray helps in detection of pneumothorax, pneumo mediastinum, and pleural effusion. An X-ray abdomen erect and lateral view is helpful in diagnosing intraperitoneal air. If perforation is suspected on clinical grounds, water-soluble contrast such as hypaque or gastrografin are to be used to confirm perforation. If there is a high risk of suspicion for perforation and the X-rays are negative, computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck, chest, or abdomen with oral contrast should be considered.

On contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) scan of the thorax: grade 1 shows normal esophageal wall; grade 2 has oedematous wall; in grade 3, peri-esophageal soft-tissue infiltration is added to grade 2 with well-demarcated tissue interface; and grade 4 has grade 3 changes along with blurring of tissue interface. Miniprobe endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be used safely. When compared with conventional endoscopy, there was no difference in predicting the development of early complications. However, a study indicated that strictures were not formed if the muscle layer was seen intact in EUS. Radial EUS is indicated if the proper muscle layer is included, treatment response to balloon dilatation decreases, or subsequent repeated procedures are required.

Endoscopy is contraindicated in hemodynamically unstable patients with necrosis around the lip and oral cavity, severe laryngopharyngeal oedema, severe respiratory distress, and suspected perforation.

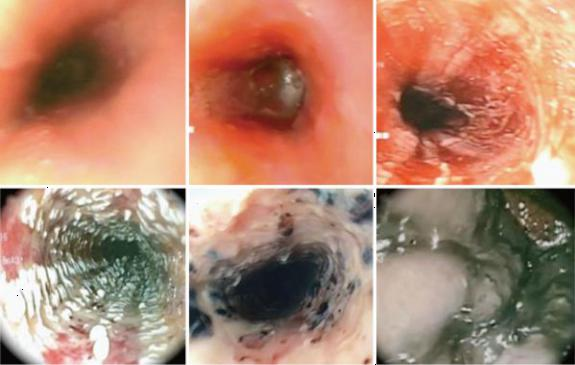

Endoscopy is usually recommended in the first 12–48 hours although it is safe up to 96 hours after caustic ingestion. Endoscopy should be performed with caution and gentle insufflation. Zargar’s modified endoscopic classification of corrosive ingestion is useful in grading endoscopic lesions: grade 0 is normal; grade 1 has mucosal edema and hyperemia; grade 2A shows superficial ulcers; grade 2B has deep focal and circumferential ulcers; grade 3A shows focal necrosis; grade 3B has extensive necrosis; and grade 4 shows perforation. [3]

Fig. 4: Endoscopic pictures of Zargar’s classification 0 to IIIB.(a) Zargar Grade 0: normal mucosa; (b) Zargar Grade I: oedema and erythema of the mucosa; (c) Zargar Grade IIA: hemorrhage, erosions, blisters, and superficial ulcers; (d) Zargar Grade IIB: circumferential bleeding ulcers. exudates;

(e) Zargar Grade IIIB: focal necrosis, deep gray, or brownish black ulcers; (f) Zargar Grade IIIB: extensive necrosis, deep gray, or brownish black ulcers

Treatment

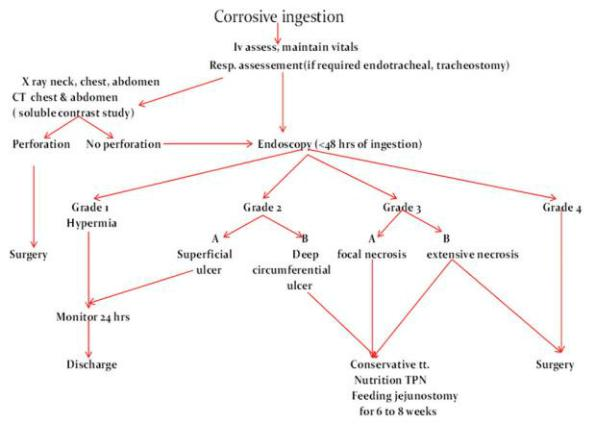

Initial management includes getting intravenous access and replacement of fluids. After stabilization, patients should be monitored for identifying acute complications and risk for development of long-term complications. Patients with stridor and respiratory distress require admission in the intensive care unit. Persistent respiratory distress mandates urgent endotracheal intubation. In patients with severe supraglottic edema, urgent cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy should be performed. Patients with clinical and imaging evidence of perforation require immediate laparotomy followed by oesophagectomy, cervical oesophagostomy, concomitant gastrectomy, and feeding jejunostomy. [Table 1]

Patients with injuries up to grade 2A have excellent prognosis and can be discharged after 24–48 hours of observation. Patients with grade 2B and 3A injury develop strictures in 70%–100% cases. All patients with grade 2B and 3A injuries can be managed conservatively; they require nutritional support for 6–8 weeks by total parenteral nutrition or feeding jejunostomy. The strictures usually develop within 8 weeks in 80% of patients but can develop as early as after 3 weeks or as late as 1 year after caustic ingestion. Patients with grade 3B and 4 have high early mortality rate up to 65%. Patients with grade 4 injury should be subjected to surgery. [3][4]

Table 1: Algorythm of acute and subacute corrosive injury management

Corticosteroids and nasogastric tube insertion are not recommended for stricture prevention. However, nasogastric tube can be placed endoscopically and has theoretical advantage of providing patent route for enteral feeding, maintain luminal integrity, and decrease stricture formation. Antibiotics do not affect scar formation. They are only indicated if there is evidence of infection or as an adjunct to the steroid therapy.

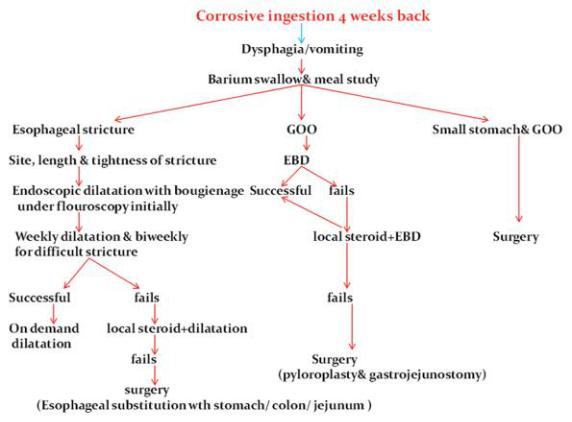

Endoscopic topical application of mitomycin-C can decrease the number of dilatations and cause relief of dysphagia.[5] Intraperitoneal 5-fluorouracil, antioxidants, and phosphatidylcholine inhibitor have been tried without success in preventing stricture formation. Intraluminal stents of silicone rubber and polytetrafluoroethylene are positioned by endoscopy or through laparotomy for 4–6 months; they have been found to be efficacious in 52%–72% but have a high migration rate (25%) and require high endoscopy skills for placement. All patients after 3–4 weeks of conservative treatment for grade 2B injury and above are subjected to barium studies for the esophagus and stomach to evaluate the length, number, degree of esophageal stricture length, shape of gastric outlet stricture, and evaluation of gastric body and fundus [Table 2]

Table 2: Algorithm of chronic corrosive injury management

Late Complications

Oesophageal stricture is the most prevalent late complication present with dysphagia. The diagnosis is based on barium swallow study. Treatment of choice is frequent wire-guided endoscopic dilatation.Reconstructive surgery is the last option when the dilatation fails. The incidence of oesophageal carcinoma is 1000-3000 fold higher after chronic caustic injury. [3]

Gastric outlet obstruction is less common than oesophageal stricture and it represents 5 % of the overall corrosive injury. Endoscopic balloon dilatation can achieve adequate diameter but surgery is the only modality of treatment for gastric complications. [3]

Conclusion

Corrosive injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract is a common problem with variable clinical presentations. In Western countries, alkaline agent injuries are more common, whereas acid injury is more common in developing countries due to easy accessibility of the agent. The depth of injury is the most important determinant of the outcome. Early endoscopy is helpful in assessing the extent of injury to plan future management of the patient. Nutritional support is given by total parenteral nutrition and feeding jejunostomy in subacute stage in grade 2B and 3A injuries. Nasogastric tube and antibiotics have no role in preventing stricture. The role of steroid remains still uncertain in the prevention of strictures. Surgery remains the last option for endoscopic failure and for patients who develop complications on endoscopic dilatation.

Take Home Message

- To get genuine history from patients or relatives plays an important role Management.

- GI endoscopy is pivotal role, but depends on local facility and expertise.

- Regular follow up with continuous assessment is paramount important because it’s chronic course of disease and can determine management plan.

Reference:

- Zagar SA et al . Ingestion of corrosive acids. Spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. Gastroenterology 1989;97:702-7

- Siew M.K,,, et al: Corrosive injury to upper gastrointestinal tract ; Still a major surgical dilemma. World J gastroenterol 2006; 12 ( 32 ) 5223-5228

- Babu, L.M. et al. Corrosive Injuries of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. J Dig Endosc 2017;8: 165-9

- Bonavina, et al. World journal of Emergency Surgery ( 2015 ) 10:44 : Foregut caustic injuries: results of the world society of emergency surgery consensus conference

- Asada,M. et al.. World J gastrointest Endosc 2018 Oct 16; 10 ( 10 ) : 274-282. Role of Endoscopy in caustic injury of the oesophagus

- Maull KI et al. Surgical implications of acid ingestion. Surg Gynaeco Obstet 1979;148:895-898