Introduction

Hyperthyroidism is a frequently diagnosed condition in both inpatient and outpatient settings. Medical treatment with anti-thyroid medication is usually the first line treatment unless contraindicated. In the UK, Carbimazole has been widely used 1 since it was licensed in 1953. One of the rare but serious side effects of carbimazole is agranulocytosis. It is well-documented in literature that the incidence is 0.3-0.6% and can occur within 3 months of initiation 2, 3 and has mortality as high as 21.5% 4.

The plausible underlying mechanisms for agranulocytosis was first explained by Sprikkelman et al. 5, 6. Four different immunological mechanisms were proposed. First, antibody production occurs when the drug attaches granulocytes, resulting in the destruction of granulocytes. Second, antibodies may target the drug metabolite complex on the neutrophil granulocyte in presence of plasma component. Third, the drug may trigger autoantibodies. Finally, the interaction between the granulocyte antigen and the drug may induce the production of antibodies 6.

Carbimazole-induced agranulocytosis can be successfully treated by GCSF (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor) 7. It enhances the recovery of the peripheral blood granulocyte lineage which results in the faster normalisation of peripheral granulocyte count as well as reduction in chances of fatal complications like bacterial infections 8.

Case report

A 37-year-old lady of South Asian origin was admitted acutely unwell to emergency department with a 48-hour history of high fever, rigor, sore throat, mouth ulcers and headache. There was no report of having neck pain, photophobia, rash, night sweats, cough, abdominal, joints, back or flank pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, dysuria, or lymphadenopathy. She lives with her husband and two children, 8 and 12 years of age, who were all well. She did not have any travel history outside of the UK in the last two years.

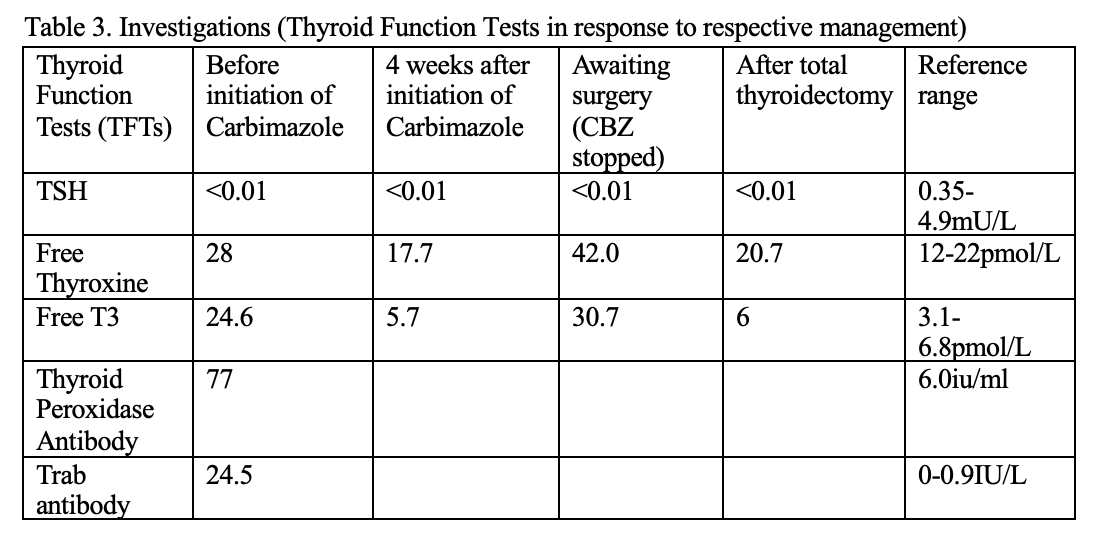

A month ago, she was diagnosed with autoimmune hyperthyroidism (AIH), when she presented with a significant weight loss of 2 stone, palpitation, tremor, restlessness, and insomnia of 6 weeks duration. There was no report of viral illness prior to development of these symptoms, neck swelling or tenderness. Biochemically, TSH (<0.01mU/L) was completely suppressed with raised T4 (28 pmol/L) and T3 (24.5 pmol/L). Thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO) and Trab antibodies were strongly positive (Table.3). Carbimazole 30 mg once daily was initiated along with propranolol for symptom control. Follow up in the endocrine clinic was arranged in 4 week-time with a plan of rechecking thyroid function test (TFT) a week beforehand.

On examination, she was pyrexial (39C), hypotensive (90/61mmHg) and tachycardiac (120/min). Oxygen saturation was 97% on air. Respiratory and cardiovascular examination were unremarkable. There was no murmur or peripheral stigmata of infective endocarditis. Abdomen was soft, not distended, non-tender without organomegaly or renal angle tenderness. Neither did she have signs of meningism, lymphadenopathy, joint swelling, tenderness or other obvious clinical signs of infection.

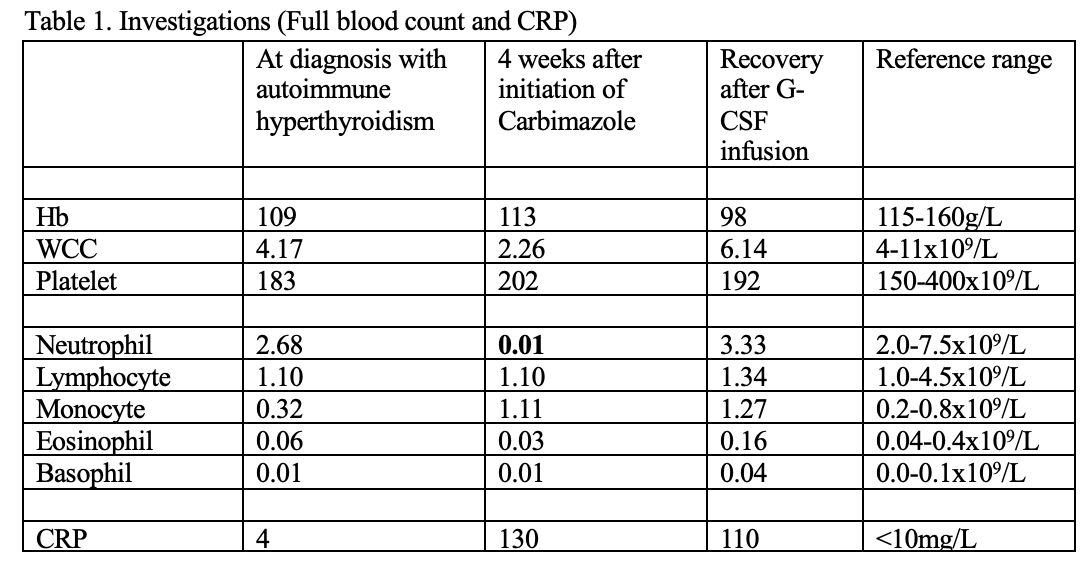

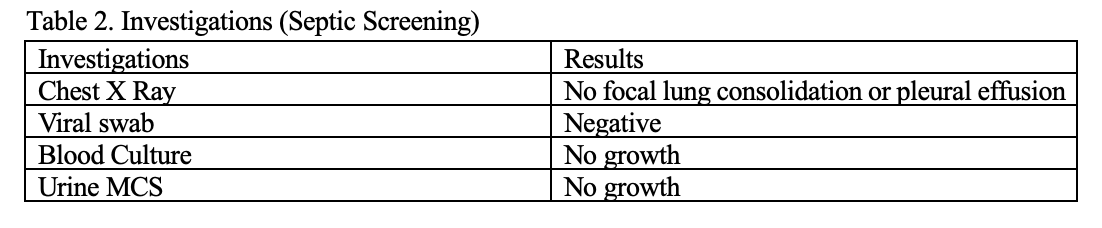

FBC showed an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 0.01×109/L with raised CRP of 130 (Table.1). Chest radiograph was unremarkable (Table.2). Septic screen including blood, urine culture and viral screen later returned negative. The peripheral blood film further confirmed severe neutropenia with reactive lymphocytes and monocytes.

She was immediately transferred to ITU for close monitoring and treated as neutropenic fever with intravenous Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin as per neutropenic fever antibiotics guideline. GCSF was also administered with close monitoring of FBC.

It was deemed that Carbimazole initiated 3 weeks ago, was the culprit of severe neutropenia and neutropenic fever and hence stopped immediately. TFT was also closely monitored. Fortunately, she made an uneventful recovery after 7 days of inpatient stay. ANC returned to normal after administration of three doses of GCSF before she was discharged home.

Endocrine team reviewed her during the inpatient stay and discussed long term management plan i.e., thyroid ablative procedures, radio-iodine therapy and thyroidectomy. She has two young children, and hence it is not possible for her to isolate after radio-iodine therapy. Therefore, thyroidectomy was the only option left. She had total thyroidectomy two weeks later without any complications.

Discussion

When the patient first presented with neutropenic fever, it was contemplated that Carbimazole was the immediate cause. However, other possible causes of neutropenia were also considered. First, Duffy-null associated neutrophil count, which is more common in individuals of African descent and ANC is typically >1.2×109/L. In this case, patient is of South Asian origin and her ANC was almost nil, hence unlikely to be of Duffy-null associated neutrophil phenotype. Second, she never has documented neutropenia in her background as well as in her family. Therefore, congenital, chronic idiopathic and familial neutropenia were less likely causes in her case. Moreover, neutropenia due to nutritional deficiencies is typically associated with other cytopenias. Although patient had anemia in previous admission, the degree of neutropenia was disproportionate and did not match with nutritional cause. In addition, she did not have history of rheumatological, autoimmune and hematological malignancies. Aplastic anemia is typically manifested as pancytopenia and the platelet count in this patient was normal. Infection as a cause of neutropenia was excluded when the septic screen including viral screen returned negative. Therefore, it was established that Carbimazole was the definite cause of agranulocytosis in her case.

Learning points

1. On reviewing clinical notes, it was noted that patient was warned of a rare but possible fatal side effect of Carbimazole, agranulocytosis, after initiation. She was educated on what symptoms to look out for if she develops the side-effect, which was well documented in her medical notes and also in clinic letter.

2. Patient recognises the nature and urgency of her illness and hence immediately sought medical attention and presented to emergency department, which saved her life.

This case clearly demonstrates the importance of patient’s education and safety netting, which is in accordance with the NICE 10 guide lines to help reduce incidence of fatal complications from idiosyncratic agranulocytosis.

Conclusion

Carbimazole induced agranulocytosis can be life-threatening if not recognised early and hence both patients and health care professionals need to be vigilant. It is of ultimate importance that patients are explained of the side-effects after initiation of medication, warned what symptoms to look out for and to seek medical attention urgently if unwell.

References

1. Abraham, P., Avenell, A., McGeoch, S.C., et al. , (2010). Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves’ hyperthyroidism (Cochrane Review). Issue 1. https://www. Cochrane library.com

2. Tajiri, J., Noguchi, S., Murakami, T., Murakami, N., (1990). Antithyroid drug-induced agranulocytosis. The usefulness of routine white blood cell count monitoring. Arch Intern Med, 1990; 150:621–4.

3. Juliá, A., Olona, M., Bueno, J., et al., (1991). Drug-induced agranulocytosis: Prognostic factors in a series of 168 episodes. Br J Haematol, 1991; 79:366–71.

4. Cooper, D.S., Goldminz, D., Levin, A.A., et al., (1983). Agranulocytosis associated with antithyroid drugs. Effects of patient age and drug dose. Ann Intern Med, 1983; 98:26–9.

5. Sprikkelman, A., de Wolf, J.T., Vellenga, E., (1994). The application of hematopoietic growth factors in drug-induced agranulocytosis: A review of 70 Cases. Leukemia, 1994;8:2031-6.

6. Mohan, A., Joseph, S., Sidharthan, N., Murali, D., (2015). Carbimazole-induced agranulocytosis. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2015;6(4):228-30.

7. Gerl, A., Gerhartz, H., Wilmanns, W., (1991). G CSF for agranulocytosis. J Intern Med .1991;230:90 1

8. Sheng, W.H., Hung, C.C., Chen, Y.C., et al., (1999). Antithyroid drug induced agranulocytosis complicated by life threatening infections. QJM. 1999;92:455 61.

9. Hyperthyroidism | Health topics A to Z | CKS | NICE

Authors

*Thinzar Myat Htwe1, *Myat Kyaw Hlaing2, **Zin Zin Htike3

Nottingham University Hospital NHS Trust, Nottingham, UK

1. Foundation Year doctor (Trust Grade, Medicine), MBBS

2. Registrar (Trust Grade, Care of the elderly medicine), MBBS, MRCP

3. Consultant Physician (Diabetes & Endocrinology) and Training Programme Director for Endocrinology (NHSE East-Midlands Deanery), MBBS, MRCP(Endocrinology), FRCP, PhD

*Joint first author

** Corresponding author