1. Introduction: Functions of the Kidneys

1.1. Overview

The kidneys are vital excretory organs playing a major role in maintaining the optimal volume and composition of the extracellular fluid (ECF) relatively constant (homeostatic function).

Through excretion in the urine, each kidney clears the blood plasma of metabolic breakdown products (including urea and creatinine from proteins, uric acid from nucleic acids), detoxification products, toxins and foreign substances like drugs and dyes. It participates in homeostasis of ECF volume (principally by handling sodium ions), tonicity or osmolality (principally by handling water), and pH (by secreting H+ ions and conserving bicarbonate ions)/

The kidneys also have endocrine functions, playing a role in the regulation of

erythropoiesis (by secreting erythropoietin),

blood volume and blood pressure (through renin angiotensin system), and

plasma calcium ion concentration (through 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol or calcitriol).

The most important and crucial function of the kidneys is disposal of metabolic wastes and other substances. No other organ can do this job for the kidneys.

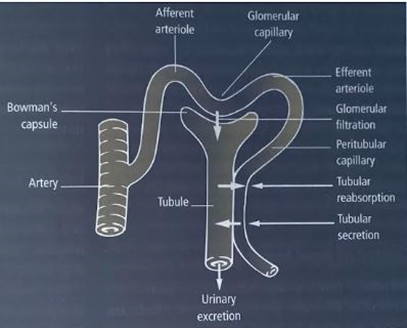

The structural and functional unit of the kidney is called a nephron. There are about 1.3 million nephrons in each kidney. The glomerulus of each nephron filters the plasma of the incoming blood and the resulting filtrate is modified along the tubule by either reabsorption (transported back into the blood) or secretion (transported from the blood into the tubular fluid) of a particular substance (see Figure 1 for diagrammatic presentation of a nephron and its associated blood vessels depicting the three basic processes involved in urine formation). The final fluid that emerges from the collecting ducts of the nephrons is the urine, which, in reality, is a waste resulting from the homeostatic activity of the kidney.

In clinical context, renal function tests are useful for identifying the presence of renal disease, monitoring the response of kidneys to treatment, and determining the progression of renal disease.

Despite the kidney performing a wide array of functions, the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is said to be the best overall indicator of renal function. This article focuses on the physiologic basis of GFR-based tests and other blood and urine tests commonly employed in clinical practice. Imaging and other specialized tests and investigations will not be dealt with in this review.

Fig 1. The three basic processes involved in urine formation: glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption and secretion. Diagrammatic presentation of a nephron and its associated blood vessels.

1.2. Glomerular Function and Renal Clearance

Filtration of plasma at the glomeruli is the crucial primary step in the excretory function of the kidneys. Without the incoming filtrate, the tubules’ modification of the filtrate, though highly homeostatic, would be redundant.

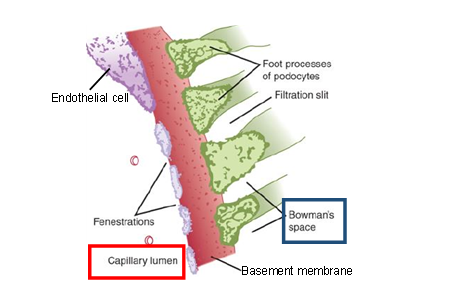

The glomerulus is formed by the invagination of a tuft of capillaries into the dilated, blind end of the tubule (Bowman’s capsule). Two cellular layers and a charged basement membrane in between separate the blood from the glomerular filtrate in Bowman’s capsule: the fenestrated capillary endothelium and the epithelium of the capsule with specialized cells (podocytes) whose numerous pseudopodia interdigitate to form filtration slits along the capillary wall. Of about 1.2 litres of blood passing through the kidneys each minute, one fifth is filtered at the glomerular membrane where not only are the particulate matter like the blood cells retained, but molecules in solution in the plasma are also selectively filtered. The ultrafiltrate entering the tubules has essentially the same composition as that of plasma, except that it is almost devoid of plasma proteins.

Fig 2. The three layers of the glomerular filtration barrier. Substances dissolved in the plasma in the glomerular capillary have to pass through (1) the fenestrations (pores) in the cytoplasm of the endothelial cell, (2) the charged basement membrane, and (3) the filtration slits (the spaces between the foot processes of the podocytes, the specialized epithelial cells of the visceral layer of Bowman’s capsule).

Glomerular filtration of a substance depends on its size as well as its electric charge. The glomerular capillary wall is permeable to molecules of less than 20,000 Daltons. Neutral substances with effective molecular diameters of less than 4 nm are freely filtered, and the filtration of neutral substances with diameters of more than 8 nm approaches zero. Since like charges repel one another, the presence of negatively charged sialoproteins in the glomerular capillary wall may explain why circulating albumin, a negatively charged protein with an effective molecular diameter of approximately 7 nm, normally has a glomerular concentration only 0.2% of its plasma concentration.

The rate at which the plasma is filtered by both kidneys, called the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is expressed as the plasma volume in millilitres filtered in one minute.

Since the volume of fluid filtered per unit time is directly proportional to the surface area of each glomerulus available for filtration, the GFR is determined by the number as well as the size of the nephrons. People with large body size would have large kidneys and hence a higher GFR while the converse is true for people with small body size. This variation is minimized by expressing the GFR per 1.73 m2 of the body surface area (generally read off from height and weight in the nomogram). A decline in the number of functioning nephrons in old age or due to disease process results in impairment of the renal excretory function with consequential rise in the plasma of metabolites such as urea and creatinine.

The normal GFR for an adult male is 90 to 120 mL/min. Some studies suggest a decrease of 7.5 mL/min/1.73m2 after 30 years due to aging processes. An otherwise healthy 70-year-old individual may have a GFR of 60 mL/min/1.73m2.

Renal clearance of any substance is defined as the volume of plasma cleared of that substance by the kidneys per minute. It is also referred to as plasma clearance, as it refers not the amount of the substance removed but to the volume of plasma from which that amount was removed (cleared) by the kidneys over an interval of time. Renal clearance is expressed as ml/min.

Clearance of a substance (say z ) is calculated using the following formula:

Cz = (Uz × V) / Pz

Where Cz = clearance of z , UCr =urinary concentration of z (mg/dL), V=urine flow rate (volume/time in mL/min), and Pz = plasma concentration of z (mg/dL).

If a particular substance in the plasma is freely filtered but neither reabsorbed nor secreted, not metabolized or stored in the kidneys, then the amount of that substance filtered per unit time can be presumed to be equal to the amount of that substance excreted in the urine per unit time.

The amount of the substance filtered per unit time is the product of the plasma concentration (mg/ml) of the substance (denoted by P) and the GFR (ml/min), i.e.

The amount of the substance filtered per unit time

= concentration of the substance in plasma (mg/ml) x GFR (ml/min).

= P x GFR

The amount of a substance excreted in the urine per unit time is the product of the concentration (mg/ml) of the substance in urine (denoted by U) and the urine flow rate (ml/min) (denoted by V).i.e.

The amount of a substance excreted in the urine per unit time

= concentration of the substance in urine (mg/ml) x urine flow rate (ml/min).

= U x V

Since all of the substance filtered appears in the urine without any modification (gain or loss) along the tubules,

amount of substance filtered per unit time = amount of substance excreted in the urine per unit time

P x GFR = U x V

Therefore GFR = (U x V) /P

But by definition,

clearance (C) of that substance = (U x V) /P

Hence the clearance of that substance is the same as GFR. In other words, GFR can be determined from the clearance of any substance that is endogenously produced by the body at a relatively fixed rate, freely filtered at the glomerulus, without being secreted or reabsorbed by the tubules, stored or metabolized in the kidneys or eliminated elsewhere in the body.

The clearance of a substance equals the GFR if there is no net tubular secretion or reabsorption, exceeds the GFR if there is net tubular secretion (since the numerator U will be greater) and is less than the GFR if there is net tubular reabsorption (since the numerator U will be lesser).

No endogenously produced substance meets all the above requirements of an ideal GFR marker. Hence exogenous markers such as inulin and radioisotopes chromium-51 Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (51 Cr-EDTA) and technetium-99-labeled diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (99 Tc-DTPA) are used to assess GFR.

Determination of inulin clearance is considered the reference method for estimating GFR. Being exogenous (not the normal constituent of plasma), inulin has to be infused into the blood stream until its plasma levels become stable. After its equilibration with body fluids, timed urine specimen is collected (as accurately as possible) and a plasma sample is obtained halfway through the urine collection. Plasma and urinary inulin concentrations are determined and the clearance is calculated. Although these exogenous markers provide the most accurate estimation of GFR, the procedure involved is laborious, time consuming, expensive, and is not routinely available in most primary care centres,. The requirement to undergo these tests in specialized facilities may render these tests impractical in general practice. As such, an endogenous marker that can circumvent these limitations becomes desirable. Hence the use of creatinine clearance as an indicator of GFR.

Creatinine is a breakdown product of muscle protein creatine, and is usually produced at a fairly constant rate by the body depending on muscle mass. Though not perfect, creatinine is the most commonly used endogenous marker for assessing glomerular function and its clearance value indicates the GFR. Creatinine clearance is calculated using the following formula:

CCr = (UCr × V) / PCr

Where CCr = creatinine clearance, UCr =urinary concentration of creatinine (mg/dL), V=urine flow rate (volume/time in mL/min), and PCr = plasma concentration of creatinine (mg/dL).

The procedure involves collecting urine over 24 hours or over another accurately timed period of 5 to 8 hours. Since some creatinine is secreted by the tubules, creatinine clearance overestimates GFR by around 10% to 20%. However, when a widely available and relatively inexpensive alkaline picrate method is used to determine concentration of creatinine, its clearance values agree quite well with the GFR values measured with inulin. Although the value for (UCr × V) is high due to tubular secretion of creatinine, the value for PCr is also high because the alkaline picrate method is not very specific and measures small amounts of other plasma constituents, and the errors tend to cancel each other. However, when precise measurements of GFR are needed, it seems unwise to rely on a method that owes what accuracy it has to compensating errors.

1.3. Tubular functions

The renal tubules play a crucial role in reabsorbing glucose, amino acids, water and electrolytes such as sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, magnesium, and phosphate ions and maintaining water, electrolyte and acid-base balance.

The bulk of the tubular work is done by the proximal tubule, while the distal nephron (the distal convoluted tubule and the collecting duct), under the influence of hormones such as vasopressin, and mineralocorticoids, handles water and electrolytes according to the needs of the body. The proximal tubule reabsorbs all of the filtered glucose and potassium and about two thirds of the filtered sodium and water. The long loops of Henle of some of the nephrons (juxtamedullary nephrons) create medullary osmotic pressure gradient which is utilized by the collecting ducts for water reabsorption by osmosis under the influence of hypothalamo-adenohypophyseal hormone vasopressin. Loss of nephrons leads to reduction in the magnitude of the medullary osmotic pressure gradient with subsequent decline in urine concentrating power of the kidneys.

Proteins, because of their size and electric charge, do not readily pass through the glomerular filter. Most of the small fraction of filtered proteins are completely reabsorbed and metabolized by the proximal tubule cells. Thus, proteins are normally present in urine in trace amounts.

Glucose, amino acids, and bicarbonate ions are reabsorbed along with sodium (Na+) in the early portion of the proximal tubule. Essentially all of the glucose is reabsorbed, and no more than a few milligrams appear in the urine per 24 h. Normally about 99% of the filtered Na+ is reabsorbed along the tubule.

Much of the filtered potassium (K+) is removed from the tubular fluid by active reabsorption in the proximal tubules, and then secreted into the fluid by the distal tubular cells. Adrenal mineralocorticoids such as aldosterone increase tubular reabsorption of Na+ in association with secretion of K+ and H+ and also Na+ reabsorption with Cl−.

The tubular and collecting duct cells secrete H ions even against the concentration gradient. There is, however, a limit to this gradient which is equivalent to tubular fluid pH of 4.4. This means even in conditions of acidosis, despite increased H ion secretion by the tubules, the urine pH could not be lower than 4.4. Titratable acidity of urine represents the H+ which is buffered mostly by phosphate which is present in significant concentration in the distal tubular lumen (titratable acid is the amount of strong base needed to titrate the urine pH back to 7.4.)..

About 98–99% of the filtered calcium Ca2+ is reabsorbed, 60% in the proximal tubules and the remainder in the ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the distal tubule where the reabsorption is stimulated by parathyroid hormone. About 85–90% of the filtered phosphate (Pi) is reabsorbed; active transport in the proximal tubule accounts for most of the reabsorption, and this is inhibited by parathyroid hormone.

Derivatives of hippuric acid in addition to paraaminohippuric acid (PAH), phenol red and other sulfonphthalein dyes, penicillin, and a variety of iodinated dyes are actively secreted into the tubular lumen. Because extraction of PAH from the incoming blood is almost complete, clearance of PAH is used to estimate renal plasma flow (and renal blood flow is calculated from the haematocrit value). This estimation, however, is mainly done for research purposes.

As the kidneys play a central role in the regulation of body fluids, electrolytes and acid-base balance, renal failure predictably results in multiple derangements including hyperkalemia, dysnatraemia, metabolic acidosis and hyperphosphatemia.

Tubular function tests involve evaluation of functions of the proximal tubule (i.e. tubular handling of sodium, glucose, phosphate, calcium, bicarbonate and amino acids) and distal tubule (urinary acidification and concentration).

Urea and electrolyte (U&E) panel is commonly used to assess renal function and fluid and electrolyte status.

Qualitative or quantitative estimation of excreted substances in the urine and evaluation of urine characteristics through physical observation, chemical, and microscopic examination (urine analysis) are useful in the assessment of tubular functions.

1.4. Endocrine functions

Erythropoietin (EPO), a glycoprotein hormone which facilitates red blood cell maturation and mediates erythropoiesis, is produced by the peritubular capillary endothelium of the kidney in response to reduced oxygen tension (hypoxia). Erythropoietin is also produced by the fetal liver, but after birth the production shifts to the kidneys. The liver maintains a production capacity of 10% of the total EPO-production, but can be up-regulated.

Renin is a protease that cleaves circulating plasma protein Angiotensinogen to form Angiotensin I. the first step in the activation of the renin angiotensin system (RAS). Angiotensin I is converted to Angiotensin II by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in pulmonary circulation. The primary source of renin in the circulation is the juxtaglomerular (JG) cells of the kidney where its expression and secretion are tightly regulated by two mechanisms: a renal baroreceptor and sodium chloride delivery to the macula densa. Through these sensing mechanisms, plasma renin levels can be incrementally titrated in response to changes in blood pressure and salt balance. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is a critical regulator of blood volume, electrolyte balance, and systemic vascular resistance.

The 25-hydroxycholecalciferol formed in the liver is further converted in the proximal tubules to the active metabolite 1, 25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (calcitriol). This hormone raises plasma calcium and phosphate levels by promoting their intestinal absorption and by causing bone resorption. Calcitriol and parathormone from the parathyroid glands are key hormones maintaining calcium ion homeostasis.

Plasma levels of EPO, plasma renin activity (PRA) and calcitriol are measured as part of the diagnosis and treatment of anaemia, hypertension and hypocalcemia rather than as primary tests for renal function.

2. Renal function tests

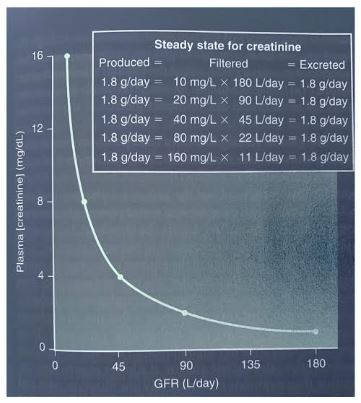

Assessing the many functions of the kidneys individually can be difficult and expensive. In clinical practice, evaluation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is central to the assessment of kidney function. The GFR is the gold standard marker of kidney health. Accuracy in GFR measurements demands complex methods using exogenous filtration markers (e.g. inulin, 51Cr-EDTA). For clinical purposes, accuracy has to be sacrificed for practicality, using instead creatinine, a versatile marker of this filtration function (whose plasma concentration has an inverse relationship to GFR) (See Figure 3). Application of creatinine-based GFR-estimating equations facilitates the detection and management of chronic kidney disease and allows disease to be categorized according to an international staging system (see Table 1). In addition to using GFR, the detection and classification of kidney disease involves measurement of urinary albumin (or protein) concentration. The use of urinary albumin:creatinine ratios obviates the need for 24-hour urine collections.

Fig 3. The inverse relationship between plasma creatinine concentration and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). If GFR is decreased by half, plasma creatinine concentration is doubled when the production and excretion of creatinine are in balance in a new steady state.

2.1. Measured GFR (mGFR) and estimated GFR (eGFR)

The GFR determined from the measured values of plasma and urinary concentrations of a substance, and timed urine collection, is referred to as measured GFR (mGFR). Improper or incomplete urine collection is a major issue affecting the accuracy of these tests. Incomplete or variable bladder emptying and spillage of urine during the collection period are the common sources of error. The inconvenience of undergoing the test procedure, particularly if there is a need to travel to specialized centres, is another drawback.

To circumvent the issue of timed urine collection, GFR has been estimated from the plasma concentration of creatinine alone, and is referred to as estimated GFR (eGFR) or calculated GFR (cGFR). Although the plasma concentration of creatinine is not particularly accurate when used to establish the absolute level of GFR, it is very useful when used to follow changes in an individual patient’s renal function, especially when the GFR is significantly reduced.

Measured GFR (mGFR) remains the gold standard, but the past 20 years have seen major advances in estimated GFR (eGFR). Although both eGFR and mGFR are not free from technical errors in estimating the true GFR, eGFR is now recommended for the initial evaluation of GFR, with measured GFR (mGFR) considered an important confirmatory test.

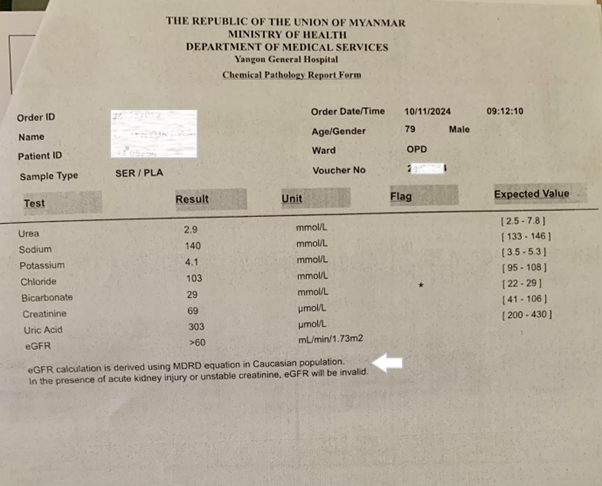

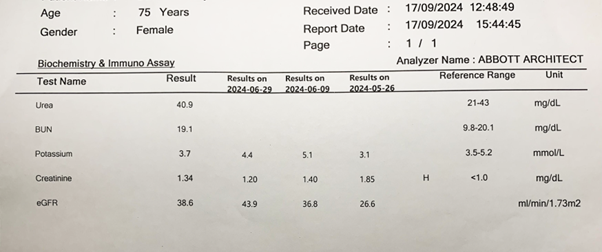

Creatinine is a breakdown product of muscle protein creatine. People produce varying amounts of creatinine, depending on their size, diet, and activity levels. To calculate eGFR, the serum creatinine levels and other information, such as the patient’s age, weight, height and sex are put into a mathematical formula, called a GFR calculator. Historically, the Cockcroft-Gault equation was used to assess renal function, but its use has been superseded in the laboratory by equations derived from studies linking creatinine concentration, along with gender and age, to eGFR, corrected for body surface area. The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula (MDRD) was recommended for use in laboratories until 2012, when guidelines suggested switching to the CKD-EPI formula which is now adopted by most major laboratories for estimated GFR (Note: The Yangon General Hospital still uses the MDRD formula (Fig. 4).

The CKD-EPI equation requires 3 variables: serum creatinine level, age and sex of the patient:

eGFR = 142 × min(SCr/κ,1)α × max(SCr/κ,1)−1.200 × 0.9938Age × 1.012 (if female)

where SCr is serum creatinine in mg/dL, κ=0.7 for females and 0.9 for males, α=−0.329 for females and −0.411 for males, min=the minimum of S/κ or 1, and max=the maximum of S/κ or 1.

Limitations of these formulas in estimating GFR include that their use is limited to adults older than 18 years and racial differences may exist. They are least reliable in extremes of body composition (malnutrition). As creatinine levels must be stable over days, eGFR is not valid in assessing acute renal failure. Since the eGFR equation uses a binary definition of gender, being a transgender or gender-diverse person could be a disadvantage. The eGFR values are consistent in individuals, and changes mean more than absolute values (see Figure 5).

Fig 4. A laboratory report on serum urea and electrolytes. Note the statement indicated by the white arrow: eGFR calculation is derived using MDRD equation in Caucasian population. In the presence of acute kidney injury or unstable creatinine, eGFR will be invalid.

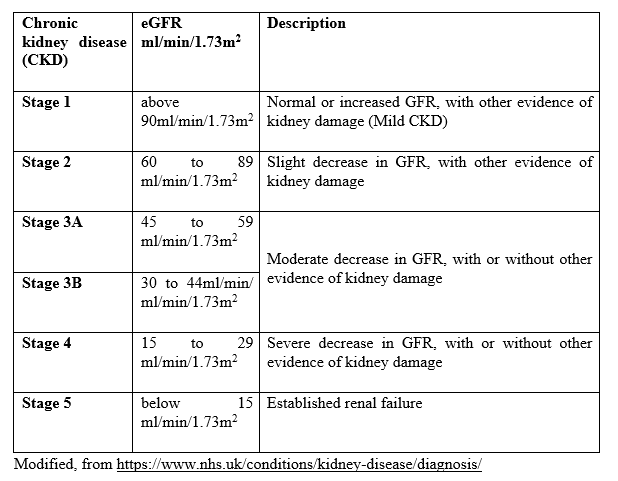

Table 1. Staging of kidney dysfunction in chronic kidney disease (CKD) according to eGFR

Serum creatinine has many limitations as a kidney function test, being affected by a variety of non-renal and analytical factors. Serum cystatin C measurement has been proposed as an alternative marker to calculate eGFR. Cystatin C is a low-molecular-weight protein that functions as a protease inhibitor produced by all nucleated cells in the body. Since cystatin C levels are not affected by muscle size, age, or diet, cystatin C could provide a more accurate estimate of GFR than creatinine. In certain cases, creatinine and cystatin levels are both used to calculate eGFR in adults. The cost of serum cystatin C analysis limits its use in general practice.

Figure 5. A laboratory report on serum urea, blood (serum) urea nitrogen, potassium and creatinine concentrations and the estimated glomerular filtration rates (eGFR). Note the reporting of serial changes in creatinine concentration and the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

2.2. Serum levels of creatinine, urea, uric acid and electrolytes

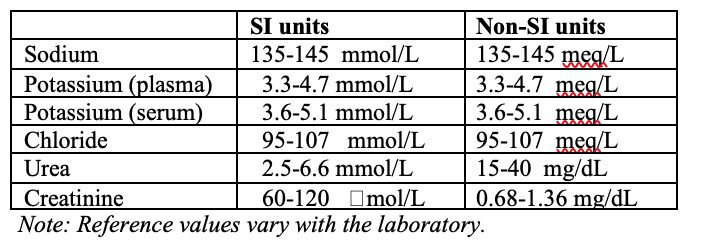

Reference values for serum urea and electrolytes are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Urea, creatinine and electrolytes in venous blood: Reference ranges for adult male are shown in SI and non SI units.

Since metabolic breakdown products are disposed of from the body principally by the kidney, deterioration of this excretory function should predictably result in the rise in the plasma levels of creatinine, urea and uric acid.

When there is slow progressive decline in the number of functioning nephrons, such as in chronic kidney disease (CKD), the only early abnormality may be an increase in the plasma levels of urea and creatinine. However, the rise in the plasma levels of urea and creatinine will not occur until 50-70 % of the nephrons are destroyed. This may be attributed to compensatory hypertrophy and increased workload of remaining (surviving) nephrons. With further destruction of the nephrons, there is a progressive increase in plasma levels of potassium, hydrogen ions (manifested as metabolic acidosis and low plasma bicarbonate), phosphate and uric acid.

Urea is the primary nitrogen-containing metabolite formed in the liver as the end product of protein metabolism and the urea cycle; amino acids absorbed from the gut are deaminated and transaminated in the liver cells and the resulting excess nitrogen feeds into the urea cycle to be incorporated into urea. Urea reaching the kidneys is freely filtered and partially reabsorbed in the tubules. Urea clearance is a poor indicator of glomerular filtration rate as its overproduction rate depends on several non-renal factors. The amount of urea produced varies with substrate delivery to the liver and the adequacy of liver function. It is increased by a high-protein diet, by gastrointestinal bleeding (whole blood is a good source of protein), by catabolic processes such as fever or infection. It is decreased by low-protein diet, malnutrition or starvation, and by parenchymal liver disease.

The serum creatinine level is less influenced by extrarenal factors than is the serum urea nitrogen level, and is the more accurate test. However, urea is increased earlier in renal disease.

In Europe, the whole urea molecule is assayed, whereas in the United States only the nitrogen component of urea (the blood or serum urea nitrogen, i.e., BUN or SUN) is measured. Even though the test is now performed mostly on serum, the term BUN is still retained by convention.

When BUN levels are increased, the BUN-to-creatinine ratio can be useful to differentiate pre-renal from renal causes. In pre-renal disease, the ratio is close to 20:1, whereas in intrinsic renal disease, it is closer to 10:1. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding can be associated with a very high BUN to creatinine ratio (sometimes >30:1).

Preanalytical issues such as high-protein intake and increased muscle mass may lead to elevated creatinine levels, but they are not representative of an individual’s renal function. Likewise, serum creatinine as a marker of renal function is often unreliable in those with decreased muscle mass, such as older people, amputees, and individuals affected by muscular dystrophy. Reference intervals for serum creatinine and urea are dependent on age and gender.

The BUN and serum creatinine are screening tests of renal function. Unfortunately, their relation to GRF is not a straight line but rather a parabolic curve. Their values remain within the normal range until more than 50% of renal function is lost. Within that range, however, a doubling of the values (e.g., BUN rising from 8 to 16 mg/dl or serum creatinine from 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dl) may mean a 50% fall in the GFR. Therefore, in the early stages of renal disease, these tests could create a false sense of security. Serum creatinine, though a useful surrogate of GFR, is a late marker of acute kidney injury. This limitation is why other substances that may be elevated earlier in the disease process are being studied as markers for kidney disease.

Uric acid is filtered, reabsorbed and secreted in the kidneys. Plasma uric acid levels rise in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and may lead to tubular injury and intra-renal inflammation. Uric acid is an independent risk factor for kidney failure in earlier stages of CKD. Further research is needed to see whether urate lowering may prove to be an effective approach to prevent complications and progression of CKD.

A sample of current report by a local laboratory on serum urea and electrolytes is shown in Fig.4.

2.3. Proteinuria, Albuminuria

Approximately one-third of the total urinary proteins is albumin, another third is a glycoprotein secreted by the tubular cells and the rest is made up of plasma proteins such as globulins. Qualitative assessment of minimal amounts of proteinuria serves as a marker for glomerular injury and risk of progression of renal disease. Debate still exists over whether to test albumin or protein levels in urine. Persistent proteinuria occurs when there is defect in glomerular membrane or in tubular reabsorption of filtered proteins, or when the tubule’s absorptive capacity is overwhelmed by excessive filtration of small proteins such as myoglobin. Looking just for albumin risks missing the presence of the two latter conditions (tubular or overflow proteinuria). Nevertheless, albumin has been found to correlate more closely with kidney disease progression in diabetes, as well as glomerular disease in hypertension.

Normally protein in urine over 24 hrs in most healthy adults is between 20-150 mg (typically albuminuria less than 30 mg/day) or 10 mg/dL The use of the urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (uACR ) has been recommended as an index of quantitative proteinuria in 24 hour urine collection. According to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, albuminuria can be classified into three stages: A1 (less than 30 mg/g creatinine; normal to mildly increased), A2 (30 mg/g to 300 mg/g creatinine; moderately increased, formerly termed as “microalbuminuria“), and A3 (greater than 300 mg/g creatinine; sternly increased). An eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and/or an uACR >30 for ≥3 months is a sign of a kidney defect.

Semi-quantitative dipstick urinalysis is a common investigation for proteinuria as this method is relatively low cost and easily performed. The finding of dipstick proteinuria should be confirmed by either a 24 hour urine collection or a protein-creatinine ratio.

2.4. Urinalysis: normal and abnormal urine

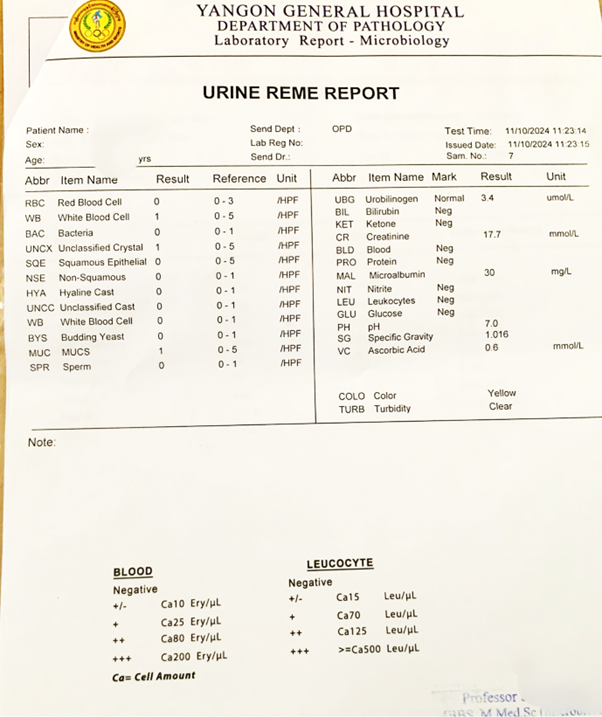

Urine analysis (urine routine examination and microscopic examination, RE, ME) involves evaluating urine characteristics to aid in disease diagnosis, through physical observation, chemical analysis, and microscopic examination. Knowledge of normal characteristics of urine is a prerequisite for this evaluation. A sample of current report by a local laboratory on urinalysis is shown in Figure 6.

Physical examination describes the volume, color, appearance, odor, and specific gravity.

Chemical examination identifies pH, red blood cells, white blood cells, proteins, glucose, urobilinogen, bilirubin, ketone bodies, leukocyte esterase, and nitrites.

Microscopic examination of the urinary deposit encompasses the detection of casts, cells, crystals, and microorganisms.

Urine samples collected from the first void or “morning urine” are considered the best representative for testing. The urine accumulated overnight in the bladder is more concentrated, and provides an insight into the kidneys’ concentrating capacities and allows for the detection of trace amounts of substances that may not be present in more diluted samples.

Volume and concentration (specific gravity, osmolality): Normally, 180 L of fluid is filtered through the glomeruli each day, while the average daily urine volume is about 1 L (typically 1,000– 1,600 mL/day). The minimal volume of 0.5 L is required to effectively excrete the metabolic wastes produced daily. The same load of solute can be excreted per 24 h in a urine volume of 500 mL with a concentration (osmolality) of 1400 mOsm/kg or in a volume of 23.3L with a concentration of 30 mOsm/kg. In terms of specific gravity, the urine concentration may vary between 1.001 and 1.040. In kidney disease, the ability to form a dilute urine is often retained, but in advanced kidney disease, the osmolality of the urine becomes fixed at about that of plasma (300 mOsm/kg or specific gravity of 1.010)(‘isosthenuria’) indicating that the diluting and concentrating functions of the kidney have both been lost.

Normally the urine is straw-colored (light/pale to dark/deep amber depending on how dilute or concentrated is the voided urine). This yellow tinge is attributed to urochrome and uroerythrin pigments. Bile pigment bilirubin is not normally present in the urine while urobilinogen, which is normally present, is colorless until oxidized to orange brown pigment urobilin on exposure to air. Red urine may indicate hematuria or porphyria or could represent the dietary intake of food such as beets.

The normal urine appeared clear or translucent; Cloudy urine may be observed in pyuria due to urinary tract infection. Foamy (bubbly or frothy) condition of urine is not routinely reported. Though foam that forms upon agitation and dissipates readily on standing is normal, more persistent foam may be associated with proteinuria, bile pigments (yellowish green froth on shaking), bile salts (due to their detergent action), retrograde ejaculation, some medications or may be non-specific or unexplained.

Odor is normally “urinoid” but not routinely reported. Some associations: fruity/sweet (diabetic ketoacidosis); fecal smell (gastrointestinal-bladder fistula); ammoniacal (prolonged bladder retention); pungent or fetid (urinary tract infection).

Normally, urine is slightly acidic, usually pH 5.5 to 6.5. The tubules secrete H ions in response to continuous production of metabolic acids in the body; normal pH range: 4.5 to 8. Urinary pH greater than 5.5 in the presence of systemic acidemia (serum pH less than 7.35) suggests renal dysfunction related to an inability to secrete hydrogen ions. On the other hand, the most common cause of alkaline urine is a stale urine sample due to the growth of bacteria and the breakdown of urea releasing ammonia. Determination of urinary pH is helpful for the diagnosis and management of urinary tract infections and crystals/calculi formation.

Test strip urinalysis, the most common technique used in routine urinalysis, exposes urine to strips that react if the urine contains certain cells or molecules. The color changes following the urine’s interaction with the chemical reagents impregnated on the dipstick paper are compared to a color chart guide to interpret the results. The urine dipstick uses dry chemistry methods to detect protein, glucose, blood, ketones, bilirubin, urobilinogen, nitrite, and leukocyte esterase and can be performed as a point-of-care test.

In healthy urine specimens, urine protein is negative; bilirubin and glucose are not detected. When blood is present, the urine dipstick detects the globin portion of hemoglobin and thus cannot detect the difference between myoglobin and hemoglobin in the urine.

In normal urine, the number of red blood cells (RBC) per high-power field is between 0 and 3, and white blood cells (WBCs) between 0 and 5. Nitrite and leucocyte esterase are indicators of urinary tract infection. Some bacteria convert nitrates to nitrites.

Urine Microscopy: The number and type of cells and/or material, such as urinary casts, crystals (calcium phosphate, calcium oxalate, uric acid), can yield a great deal of information and may suggest a specific diagnosis. Red blood cells and white blood cells: normal: 0-5 cells/high-power field. Casts, a coagulum composed of the trapped distal tubular contents (red blood cells, white blood cells, epithelial cells, bacteria) and Tamm-Horsfall mucoprotein are formed when there is alteration in pH or stasis in tubular fluid flow. Granular casts probably represent degenerate cellular casts. Hyaline casts contain no element or debris. Only a few hyaline or finely granular casts may be seen under normal physiological conditions.

Fig 6. A report on urine routine examination and microscopic examination (REME).

3. Conclusions

Evaluation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is central to the assessment of kidney function. Creatinine serves as a versatile marker of this filtration function and its serum level and the GFR calculated from it, called the estimated GFR (eGFR), are currently recommended as an initial evaluation of GFR. Measured GFR (mGFR) is considered an important confirmatory test. Comparing the serial values of eGFR is more informative than the individual absolute values. Urea and electrolyte panel, quantification of albuminuria and urinalysis are tests that supplement eGFR while many new markers of glomerular function such as Cystatin C have been emerging over the years.

References

- Tanner GA. Kidney Function. In: Rhoades RA, Bell DR (Eds.) Medical Physiology. Principles for Clinical Medicine. Baltimore; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014: 399-421.

- Barrett KE, Barman SM, Brooks HL, Yuan JX.-J. Ganong’s Review of Medical Physiology. Lange, McGraw Hill Education. (PDF format). Access Medicine, 2019: 1/39 -35/39.

- Koay ESC and Walmsley RN. Handbook of Chemical Pathology. Singapore; PG Medical Books, 1989: 90-118

- Gaddan J, Turner AN, Stewart LH. Kidney and Urinary Tract Disease. In: Colledge NR, Walker BR, and Ralston SH (Eds). Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2010: 452-468.

- Thuraisingham R. Kidneys and Urinary Tract. In: Glynn M, Drake W (Eds). Hutchison’s Clinical Methods. Edinburgh: Saunders Elsevier; 2012: 384-388.

- Sparks MA, Crowley SD, Gurley SB, Mirotsou M, Coffman TM. Classical Renin-Angiotensin system in Kidney Physiology. Compr Physiol. 2014; 4(3):1201-28. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130040. PMID: 24944035; PMCID: PMC4137912.

- Rosner MH, Bolton WK. Renal Function Testing. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 2006; 47 (1): 174 – 183.

- Gounden V, Bhatt H, Jialal I. Renal Function Tests. [Updated 2024 Jul 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507821/

- Gowda S, Desai PB, Kulkarni SS, Hull VV, Math AA, Vernekar SN. Markers of Renal Function Tests. N Am J Med Sci. 2010; 2(4):170-3. PMID: 22624135; PMCID: PMC3354405.

- Lamb E. Assessment of Kidney Function in Adults. Medicine 47(8); 2019: 482-488

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2019.05.002Get rights and content - Levey AS, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Greene T, Inker LA. Measured and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate: Current Status and Future Directions. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(1):51-64. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0191-y. Epub 2019 Sep 16. PMID: 31527790.

- Lyman JL. Blood Urea Nitrogen and Creatinine. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 1986; 4(2): 223-233.

- Srivastava A, Kaze AD, McMullan CJ, Isakova T, Waikar SS. Uric Acid and the Risks of Kidney Failure and Death in Individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018; 71(3):362-370. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.08.017. Epub 2017 Nov 11. PMID: 29132945; PMCID: PMC5828916.

- Queremel Milani DA, Jialal I. Urinalysis. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557685/

Author Information

Nyunt Wai,

MBBS MMedSc(Ygn), PhD (London)

Retired Professor and Head, Physiology Department,

University of Medicine 1, Yangon