A. Why so important?

The prevalence of seizures and epilepsy in the elderly is generally underestimated. The general impression is experiencing an epileptic seizure in the elderly represents a less important problem than in a young person.

Most of the diagnostic and therapeutic solutions are directly achieved from studies performed in a younger population, rather than from trials specifically designed for old age.

Actually, epileptic seizures are not a rare occurrence in the elderly and their prevalence increases with age.

The clinical manifestations of seizures, the etiology, the treatment, the psychosocial impact as well as differential diagnosis is often difficult in the elderly.

The presence of comorbidities, the polypharmatherapy and the age-related pharmacokinetic changes can represent a problem for the treatment of epilepsy in the elderly, with a higher risk of adverse effects and potentially inappropriate drug interactions.

Epileptic older people have mortality rates 2 or 3 times higher than non-epileptic population of their own age group.

For all these reasons, the management of the elderly with epilepsy should concerns not only to neurologists, but also general practitioners, geriatricians, and cardiologists.

With the worldwide-distributed increase of the elderly population, the problem has also assumed a considerable economic importance, with a growing weight for health care expenditure, and burden to the families.

B. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy in the elderly

The incidence of epilepsy, substantially stable between the second and fifth decades of life with 30-40 cases/100,000 persons/ year, starts to grow up from the age of 60’s, reaching an incidence of around 150 cases/100,000 persons/ year in the 80 years old subjects.

The main contribution to increasing epilepsy incidence is given by focal seizures (over 100 cases/ 100,000 persons/ year at 80 years), in relation to the typical etiology from injury rather than the generalized attacks (around 40 cases/100,000 persons/ year at the same age).

The incidence of acute symptomatic seizures is also higher with increasing age. Seizures occur in approximately 10% of patients with stroke.

The elderly are more prone to developing a first unprovoked seizure.

The incidence of this complication was 52-59 per 100,000 in individuals aged 40-59-years and increased to 127 per 100,000 in people aged 60 years or older.

The recurrence rate after the first seizure was also higher in the older population: 79% in the first year after the first seizure and 83% in the 3 years after the first seizure.

Status epilepticus (SE) is two to five times more common in the elderly than in young adults, with an annual incidence of 86 per 100,000 in individuals older than 60 years.

C. Etiology of epilepsy and seizures in the elderly

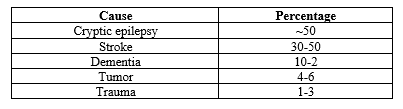

The most common cause of epilepsy in the elderly is cryptogenic or stroke-related seizure, followed by dementia and tumors (Table 1).

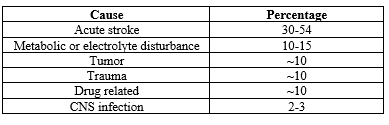

Acute stroke is also a leading cause of acute symptomatic seizures. Other common causes of acute symptomatic seizures are toxic- metabolic events and trauma (Table 2).

Table 1: Etiology of epilepsy in the elderly

Table 2: Etiology of acute seizures in the elderly

Small focal lesions with a vascular origin may not be detected by current neuroimaging techniques, and vascular lesions, including small strokes, may be a much more common cause of epilepsy.

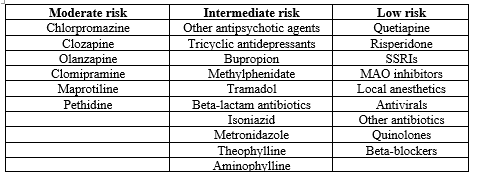

Some drugs can lower the threshold of seizures. The use of several medications in elderly individuals to treat other conditions may contribute to the occurrence of seizures. (Table 3)

D. Clinical presentation of seizures in the elderly and differential diagnosis

In the elderly, the most frequent type of seizure is focal impaired awareness seizure (not focal to bilateral tonic clonic type) (47.1%), and temporal lobe epilepsy is the most commonly diagnosed epileptic disorder (71.4%).

Table 3: Drugs and risk of seizures

Typical auras, including fear, epigastric rising sensation, and dejavu phenomena, occur at a lower rate than usually nonspecific auras such as dizziness. Postictal confusion may be longer than usual and typical symptoms, including orofacial and hand automatisms, are less common.

The diagnosis of this condition is difficult, probably because of less-specific seizure symptomology, nonspecific characteristics, more diverse and atypical, short-term symptoms, and the absence of witnesses among family members or surrounding people.

Careful history-taking and analysis of the circumstances of events that preceded the symptoms, evaluation of patient posture, presence of myoclonic jerks and confusion, duration of events, and the recurrence of episodes may lead to a correct diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis between seizures and syncope is difficult in some cases. The incidence of syncope is high in the elderly. Brief myoclonic jerks or tonic posturing is common in cases of syncope.

Table 4. Differential diagnosis of epilepsy and other seizure disorders in the elderly

Neurological

- TIA

- TGA

Endocrine/metabolic

- Hypoglycemia

- Hyponatremia

Cardiovascular

- Vasovagal syncope

Sleep disorders

- REM behavior disorder

- Parasomnia, including sleep eating disorder or sleepwalking

Other reflex syncope

- Sick sinus syndrome

- Others arrhythmia

- Postural hypotension

Psychological

- Nonepileptic psychogenic seizure

E. Critical issues in the treatment of epilepsy in the elderly

There are three relevant issues in the treatment of epilepsy for the elderly:

- changes in pharmacokinetic parameters,

- polytherapy (including non-ASMs), and

- susceptibility to adverse drug effects.

Drug absorption may be significantly delayed or decreased because of a diminished ability to absorb anti-seizure medications (ASMs) in the GI tract.

Hepatic and renal clearance is reduced with aging. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) declines by >50% between the third and eighth decades of life.

The decreased therapeutic window in the elderly may increase the vulnerability to the adverse effects of ASMs.

Changes in body composition, a reduction in total body water can lead to the lower levels of serum albumin and higher levels of free AEDs may also contribute to dose-dependent adverse effects.

There are many concomitant diseases in the elderly.

These individuals are likely to take many medications concomitantly.

Even healthy elderly subjects may take many drugs. In this aspect, the ASMs that lack pharmacokinetic interactions present an advantage.

The elderly are prone to experiencing adverse events after taking ASMs. Changes in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters can cause adverse symptoms and impair the quality of life if drug dosage remains unchanged.

The general rules are:

- avoid the occurrence of adverse effects caused by ASMs in this elderly population is to “start low and go slow. “It is better to start ASMs at a dose lower than usual and increase the dose gradually in small increments.

- monotherapy. it is a priority in the elderly

- simplify all therapies as far as possible

- know the pharmacokinetic mechanisms of the different drugs used, the possible interactions, and pay attention to their prediction.

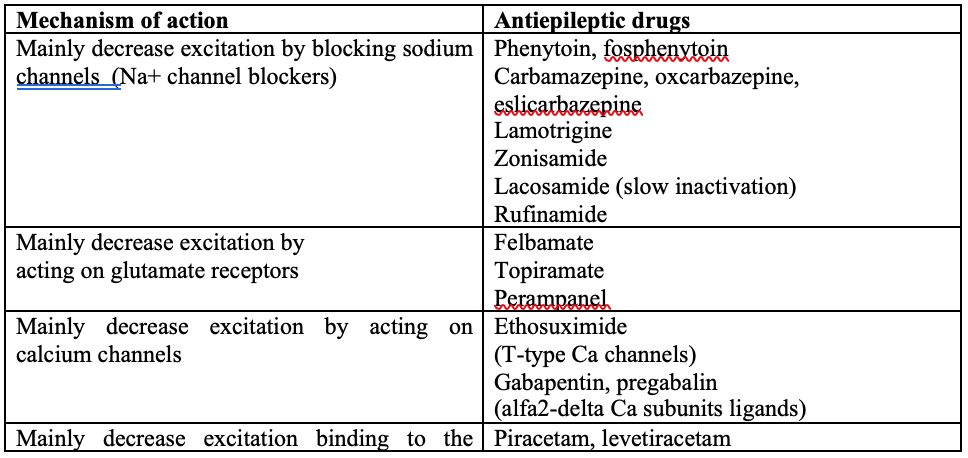

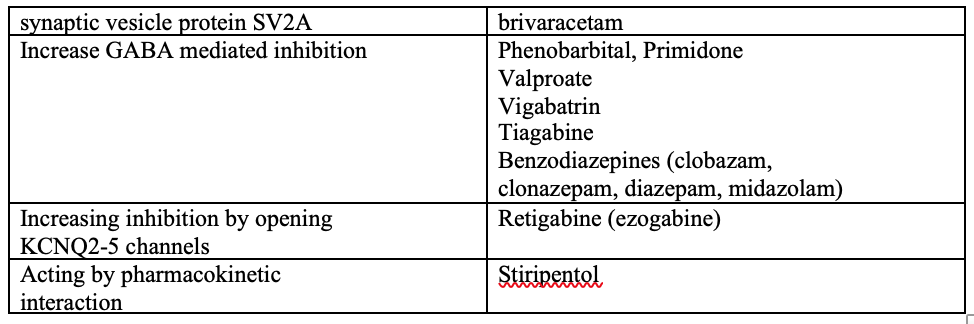

Table 5: Current antiepileptic drugs and suggested mechanism of action

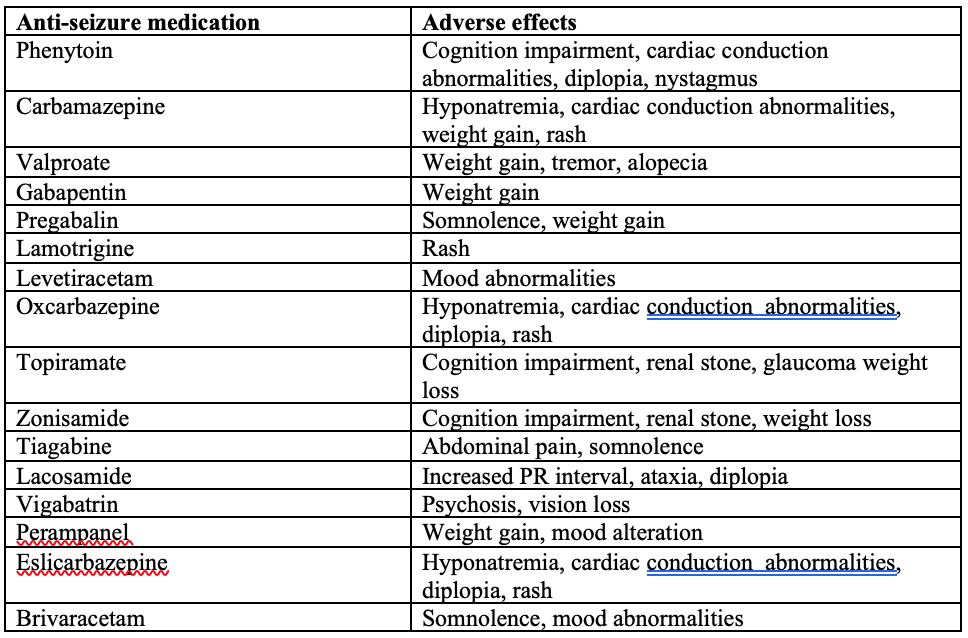

Table 6: Common ASMs and their adverse effects in the elderly

F. Choice of ASMs in elderly

The choice of the most appropriate drug in elderly epileptic patients is a complex problem, and many parameters need to be taken in consideration, including both the characteristics of epilepsy and of the patient as well.

About adverse effects on the CNS, and possibly on other organs, should be avoided.

Older ASMs

Drugs that has high pharmacokinetic interactions, and the high binding to plasma proteins are not very advisable.

Wide spectrum of effectiveness, good tolerability, modest pharmacokinetic interactions, and the possibility of rapid titration make valproate one of the possible therapeutic options.

For focal seizures in the elderly, carbamazepine is a particularly used drug, with caution and required slow titration due to possible idiosyncratic effects of skin rash

Because of more favorable kinetics, the reduced potential of enzyme induction and the better tolerability of oxcarbazepine, it is more suitable than carbamazepine in elderly.

Newer ASMs

Relatively few randomized controlled trials specifically designed for the elderly population are available, and essentially, they involve some new antiepileptic drugs. Open-label studies support the use of lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, zonisamide and lacosamide in the elderly.

The impact of epilepsy and its treatment on cognitive functions, behavior, and mood, on the elderly quality of life, considerably importance when making choices.

New ASMs brivaracetam and eslicarbazepine better advantages in terms of efficacy, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and compliance.

Eslicarbazepine has positive affect serum lipid lowering profile, in contrast to the negative impact observed with older carboxamides.

Perampanel, a non-competitive highly selective AMPA receptor antagonist is also a good ASMs in the population aged 65 or over.

Dose reduction in cases of decreased renal clearance

The dose of ASMs that are heavily metabolized or excreted through the kidney should be adjusted in elderly patients with decreased renal function to avoid the occurrence of dose-dependent adverse effects.

These drugs include ethosuximide, gabapentin, pregabalin, levetiracetam, topiramate, and vigabatrin.

The doses of these drugs may have to be reduced up to 50% in cases in which the GFR is decreased to 30-59 mL/min.

G. Stroke and epilepsy

Stroke is the most common severe neurological disorder. There is a strong association between stroke and epilepsy.

- Early post stroke seizure is defined as seizures that occur within 7 days of any stroke. This type of seizure is regarded as acute symptomatic and may be recurrent or present as status epilepticus (SE).

- Late seizures are defined as those that occur more than 7 days after stroke. This type of seizure is also known as unprovoked seizure.

- Stroke was strongly associated with a high incidence of early seizures and epilepsy.

The risk of subsequent unprovoked seizures was 33.0% among subjects with a first acute symptomatic seizure and 71.5% among individuals with a first unprovoked seizure.

Seizures may not be recognized by patients or witnesses, and the lack of awareness about this condition may be higher in older patients.

Seizures are also common after intracerebral hemorrhage and may be nonconvulsive type.

The presumed mechanism of post stroke early seizures:

- a regional metabolic dysfunction —– > the release of excitotoxic neurotransmitters —– > accumulation of calcium and sodium —– > depolarization of cellular membranes.

The causes of post stroke late-onset seizures:

- structural changes —– > gliosis, meningocerebral scarring, selective neuronal loss, deafferentiation, and collateral sprouting.

Management consideration for post stroke seizure

Prophylactic ASMs are not necessary for patients with stroke.

In the case of a single acute seizure, other metabolic causes and precipitating factors should be identified before deciding on the treatment options.

Most of these events do not usually require ASMs, except a prolonged first acute seizure, acute recurrent seizures, or SE.

If medications is required, most cases of single seizures are easily controlled using one ASM.

The early use of ASMs was not associated with a reduction in the risk of recurrent seizures after the discontinuation of these drugs.

Late seizures can be managed-

- waiting for a second late seizure that fits the definition of epilepsy or

- starting antiepileptic therapy immediately.

The decision can be made considering the patient’s general condition and the severity and impact of the seizures.

Most epilepsy events associated with stroke have a favorable outcome after treatment with ASMs.

67% of patients became seizure- free for at least 1 year, by using just a single ASM.

H. Dementia and epilepsy

The prevalence of seizures in patients with dementia is high (range, 10-22%).

The mechanism of seizures in dementia is unclear. Excessive neuronal loss, including the loss of GABA interneurons, may be responsible for the generation of seizures.

Short-term fluctuation or decrease in response and intermittent confusion can be a symptom of seizure in dementia patients.

The cognitive decline caused by seizures can be prolonged in some cases. Repetitive symptoms can be a clue leading to a correct diagnosis.

Epilepsy can aggravate the general condition of these patients and worsen memory functions. A high level of suspicion is needed.

Summary

- Epilepsy in elderly patients has quite different etiology, clinical manifestations, and choice of AMSs compare with other adult patients.

- The efficacy of ASMs, their adverse effects and drug interactions as well as comorbid diseases and economic status must be considered when choosing ASMs for treating epilepsy in elderly patients.

- ASMs that are suitable for treating epilepsy in elderly patients have:

- no interactions with other medications or AEDs,

- no or low protein binding,

- good adverse-effect profiles, and

- little effect on cognitive function

- ASM therapy simplification (monotherapy, drugs with simple kinetics) and caution (low doses, very gradual increase, attention to adverse effects and possible drug interactions, effects on cognitive performance) must be general criteria to adopt.

- The involvement of general practitioners and geriatricians, and of course the family and caregiver, is essential in the effective management of this condition.

References

- Lee SK. Epilepsy in the Elderly: Treatment and Consideration of Comorbid Diseases. J Epilepsy Res. 2019 Jun 30;9(1):27-35. doi: 10.14581/jer.19003. PMID: 31482054; PMCID: PMC6706648.

- Miller WR. Patient-centered outcomes in older adults with epilepsy. Seizure. 2014 Sep;23(8):592-7. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2014.04.010. Epub 2014 Apr 28. PMID: 24838071; PMCID: PMC4440332.

- Piccenna L, O’Dwyer R, Leppik I, Beghi E, Giussani G, Costa C, DiFrancesco JC, Dhakar MB, Akamatsu N, Cretin B, Krämer G, Faught E, Kwan P. Management of epilepsy in older adults: A critical review by the ILAE Task Force on Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia. 2023 Mar;64(3):567-585. doi: 10.1111/epi.17426. Epub 2022 Oct 20. PMID: 36266921.

- Poza JJ. Management of epilepsy in the elderly. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007 Dec;3(6):723-8. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s1026. PMID: 19300606; PMCID: PMC2656313.

- Salvatore Striano, Nicola Ferrara, Maurizio Taglialatela, Tiziano Zanoni, Graziamaria Corbi. Management of epilepsy in elderly. JGG: 2020; 68:1-9. doi: 10.36150/2499-6564-334

- Seo JG, Cho YW, Kim KT, Kim DW, Yang KI, Lee ST, Byun JI, No YJ, Kang KW, Kim D; Drug Committee of Korean Epilepsy Society. Pharmacological Treatment of Epilepsy in Elderly Patients. J Clin Neurol. 2020 Oct;16(4):556-561. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2020.16.4.556. PMID: 33029960; PMCID: PMC7542002.

- Theitler J, Brik A, Shaniv D, Berkovitch M, Gandelman-Marton R. Antiepileptic Drug Treatment in Community-Dwelling Older Patients with Epilepsy: A Retrospective Observational Study of Old- Versus New-Generation Antiepileptic Drugs. Drugs Aging. 2017 Jun;34(6):479-487. doi: 10.1007/s40266-017-0465-7. PMID: 28478592.

Author Information

Thar Thar Oo

MBBS, MD, MPH, FAAN

Senior Consultant Neurologist