Management of Hypertension in Neurology

Introduction

Hypertension is common in Neurology practice. Elevated blood pressure (BP) may be the cause or effect of Neurological disorders. The management of hypertension in Neurology is not straight forward. Even in the same clinical condition, management differs depending on underlying aetiology and general condition of patients. The timing to introduce antihypertensive medications, BP target and choice of antihypertensive agent are important issues in the management of hypertension in Neurology.

This article will focus on when to start antihypertensive medications, how to monitor BP, target blood pressure and choice of antihypertensive agent in different neurological conditions.

Neurological conditions associated with hypertension are;

- Hypertensive encephalopathy

- Acute stroke, Ischaemic or Haemorrhaegic

- Subarachnoid Haemorrhage

- Stroke prevention

Case Vignette – 1

A 35 year old right handed lady presented to the emergency department with altered mental state. She was previously well and no significant past medical history. On examination, patient was sleepy but arousable, able to answer only “Yes” or “No”, not co-operative on examination . Pupils were round and equal with good light reaction. She could move all 4 extremities symmetrically but did not follow commands. Blood pressure was 240/130 mmHg, pulse rate was100/min, she was a febrile.

Her investigations revealed;

- ECG and CXR, Blood for CBC, Creatinine and Electrolytes – normal

- CT (head) – small 4th ventricle and evidence of cerebral edema

Question: How would you manage her BP?

Discussion: This is a case of hypertensive encephalopathy. Patient should be immediately admitted to ICU and immediately have their BP lowered. Initial goal is to reduce MAP by 25% within the first few hours. Intravenous treatment with a drug with short half life is ideal. Patient need close haemodynamic monitoring and should avoid pronounced fluctuation of blood pressure.

1st line drugs are Nicardipine (or) Labetalol.

Nitropresside can be used as 2nd line drug. However, it has disadvantages of venodilatation associated with increased intracranial pressure and possible toxic effect.

Hydralazine is less desirable than other drugs because of unpredictable effect and variable effect on intracranial pressure and circulation.

Case vignette – 2

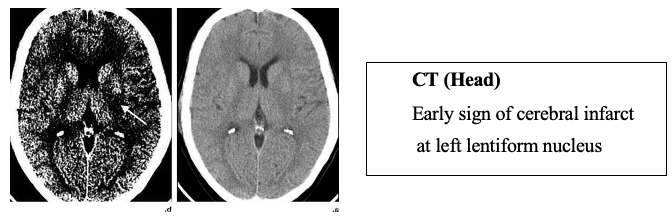

A 54 year old right handed lady presented with sudden onset of right hemiparesis and slurred speech 1 hour ago. She did not have any medical checkup previously. On examination, GCS was 15/15, right facial palsy (UMN), slurred speech, right hemiparesis (power 3/5), up going planter response on right side. NIHSS score was 12. Blood pressure was 180/110 mmHg, pulse was 84/min, heart and lungs were unremarkable. Complete blood picture, urea and electrolytes, creatinine and coagulation profiles were normal.

- ECG and CXR – Normal

Question: How would you manage her blood pressure?

Discussion: To treat or not to treat high BP in acute ischaemic stroke has been debated for more than 30 years ago and there was no definitive answer till 2018. Based on dysfunctional cerebral auto-regulation during acute stroke, there is concern about lowering BP due to:

- Reduce tissue perfusion

- Increase lesion size

- Worsen outcome

In addition, causes of high BP in acute stroke include:

- Prior hypertension

- Acute neuroendocrine stimulation (via RAA System, sympathetic autonomic nervous, and corticotrophin-cortisol systems, Cushing reflex

- Stress associated with admission to hospital

- Concurrent pain (eg. due to urinary retention)

All these factors offer multiple targets for treatment during acute ischaemic stroke.

There were studies on blood pressure management and outcomes of acute ischaemic stroke. Most of these studies showed negative effect on stroke outcome in blood pressure lowering group. On the other hand, studies about effect of hypertension on thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke revealed hypertension is one of independent risk factors for symptomatic intracerebral haemorrhage and substantial blood pressure decrease before, during and 24 hour post thrombolysis was associated with favorable outcome in acute ischaemic stroke. Based on these different results, blood pressure level should be maintained in patients with acute ischaemic stroke to ensure best outcome is not known.

Recent guidelines stated that management of hypertension depends on –

- Whether patient is eligible for acute reperfusion therapy or not

- Presence of co morbid condition

- Neurological status

For patients with elevated BP and eligible for treatment with IV alteplase

Blood pressure should be carefully lowered to systolic BP <185 mm Hg and diastolic BP

<110 mm Hg before intravenous fibrinolytic therapy. Options of treatment in this situation are;

- Labetalol – 10–20 mg intravenously over 1–2 min

- May repeat 1 time

OR - Nicardipine 5 mg/hour intravenously, titrate up by 2.5 mg/hour every 5–15 minute, maximum 15 mg/hour

OR - Clevidipine 1–2 mg/hour intravenously, titrate by doubling the dose every 2–5 minute , maximum 21 mg/hour

Other agents that can be used are Hydralazine and Enalaprilat.

If BP is not maintained ≤185/110 mm Hg, alteplase should not be administered. Blood pressure should be maintained at ≤180/105 mmHg during thrombolysis and 24 hours after thrombolysis.

For patients with co morbid conditions

Early treatment of hypertension is indicated in patients with concomitant

- Acute coronary event

- Acute heart failure

- Aortic dissection

- Post-thrombolysis spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage

- Preeclampsia/eclampsia

It should be kept in mind that excessive BP lowering can sometimes worsen cerebral ischemia. Lowering blood pressure initially by 15% is probably safe in these patients.

For patients with no comorbid condition and did not receive reperfusion therapy

In patients with blood pressure > 220/120 mmHg, it might be reasonable to lower BP by 15% during the first 24 hours after onset of stroke.

If patient’s neurological status becomes stable and blood pressure is >140/90 mmHg, starting or restarting antihypertensive therapy is safe and reasonable to improve long-term BP control.

Case vignette – 3

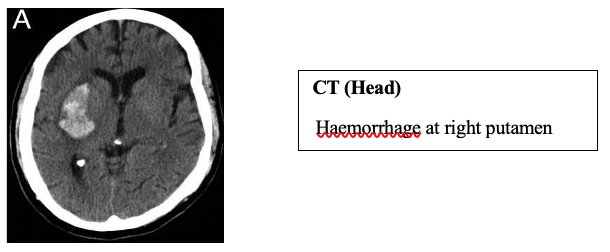

A 60 year old right handed man came to emergency department for sudden onset of left hemiparesis. His weakness was preceded by bi-temporal headache and he experienced vomiting once in home. He denied any head injury. He had history of hypertension since 5 years ago and took Amlodipine as prescribed by GP, only when he had high BP and stopped by himself if BP was normal.

On examination, GCS was 15/15, pupil was 2 mm, equal with good light response. There was left facial palsy (UMN) and left hemiparesis.

BP was 180/110 mmHg, pulse rate was 88/min. Heart and lungs were unremarkable. Investigation results showed normal haematological and biochemical parameters, left ventricular hypertrophy in ECG and mild cardiomegaly in CXR.

Question: How would you manage BP in this patient?

Discussion: This is a case of primary ICH. Patients with ICH very often present with significantly elevated blood pressure.

Elevated systolic BP is associated with

- Haematoma expansion

- Neurological deterioration

- Poor outcome after ICH

In the past, there was concern about peri-haematomal ischaemia from aggressive early BP reduction. However, studies with advanced neuroimaging confirmed that there was no significant ischaemic penumbra in ICH and peri-hematomal rim of low attenuation on CT being related to extravasated plasma.

Meta analysis of 4 eligible studies confirmed that intensive BP management in patients with acute ICH is safe and associated with greater attenuation of absolute haematoma growth at

24 hours.

According to 2015, AHA/ASA Guidelines for ICH,

In patients with SBP between 150 and 220 mmHg, without contraindication, acute lowering of SBP to 140 mmHg is safe and effective for improving functional outcome.

In patients with SBP >220 mmHg, it is reasonable to consider aggressive reduction of BP with continuous IV infusion and frequent BP monitoring. In these patients, IV Calcium Channel Blockers (Nicardipine) and β- blockersz (Labetalol) are preferable antihypertensive agents because of their short half life and ease of titration. Nitrates should be avoided because of cerebral vasodilatation and elevated ICP effect. Oral antihypertensive agents need to be started as soon as possible to control resistant hypertension.

Case vignette – 4

A 47-year-old lady was admitted to emergency department with headache and vomiting. Her urgent CT scan revealed subarachnoid hemorrhage. Her BP was 180/110 mmHg.

Question: How would you manage her BP?

Discussion: According to 2012 AHA/ASA guideline, between the time of symptom onset and aneurysm obliteration, blood pressure should be controlled to balance the risk of stroke and hypertension-related re-bleeding and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure.

Magnitude of blood pressure control to reduce the risk of re-bleeding has not been established but decrease in systolic blood pressure to <160 mm Hg is reasonable. Regarding antihypertensive agent, Nicardipine has smoother control than labetalol and sodium nitroprusside.

Management of blood pressure in stroke prevention

Hypertension is strongly linked to small vessel cerebrovascular disease; lipohyalinosis- related lacunar infarction and also a major cause of atherosclerotic stroke. Antihypertensive therapy gives consistent benefit of stroke prevention and it has been observed in all large RCTs using different drug regimen. Both systolic BP and diastolic BP reduction are linearly related to the lower risk of recurrent stroke. For primary prevention of stroke, strict BP control is important.

According to 2017 ACC guideline, BP ranging from 130/80 to 140/90 mmHg is considered as stage 1 hypertension and should be treated in all individuals with symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and asymptomatic individuals with 10-year ASCVD risk over 10%.

For secondary stroke prevention, patients with BP higher than 140/90 mmHg should be initiated or restarted antihypertensive agents immediately after TIA and 72 hours after stroke. BP target should be generally 130/80 mmHg and lower systolic BP target of less than 130 mmHg is recommended after lacunar stroke.

Choice of antihypertensive agents for stroke prevention

Primary prevention of stroke

Evidence with Renin Agiotesin Aldosterone (RAA) system blockage

HOPE, LIFE and ON TARGET studies confirmed that angiotensin receptor blockers are effective in primary stroke prevention.

Evidence with calcium channel blockers (CCB)

ACTION Study and ASCOT –BPLA Study showed that CCB can prevent fatal and non fatal stroke.

Evidence with Diuretics

SHEP Study showed that Chlorthalidone caused 36% reduction in the incidence of stroke. However, because of their lower tolerance and efficacy on regression of target organ damage compared with ARB, ACEI and CCB, it is rarely use alone as 1st line therapy for primary stroke prevention.

Secondary prevention of stroke

Evidence with Renin Agiotesin Aldosterone (RAA) system blockage

According to PROGRESS Study, PRoFESS Study and TRANSCEND Study, ACEI

and ARB are effective in prevention of further stroke.

Evidence with calcium channel blockers (CCB)

According to Canadian Stroke Network, there was no change in 6 month mortality between groups of patients treated with CCB and non-CCB. However after 6 months, CCB group had improved stroke Impact Scale-16 compared with others.

In conclusion, control of high blood pressure is important for both primary and secondary stroke prevention. Those acting on RAS blockage, CCB and Thiazide diuretics represent three classes with strongest effect in primary stroke prevention. For secondary stroke prevention, there is evidence with medicines acting on RAA system blockage and CCB. However, reduction in BP is more important than choice of specific agents and it should be considered based on patient’s co morbidities such as presence of intracranial artery stenosis, renal impairment and diabetes mellitus.

Key Points

- Immediate BP lowering is indicated in hypertensive encephalopathy

- I.V treatment with short half life is ideal

- In acute ischaemic stroke, BP reduction may depend on

– Whether patient will undergo reperfusion therapy

– Presence of co morbid condition

– BP Level in acute setting - Target BP in case of IV Thrombolysis- <180/105 mmHg and maintain for 24 hours • In acute ICH, rapid reduction of BP should be considered if SBP >220 mmHg

- Target BP – SBP<140 mmHg

- In case of SAH, BP should be controlled to balance risk of stroke, hypertension related re- bleeding and maintenance of cerebral perfusion pressure

- Target BP – SBP <160 mmHg

- For primary stroke prevention, individuals with symptomatic ASCVD or 10 year

ASCVD risk over 10% should receive BP lowering treatment when BP is 130/80 –

140/90 - For secondary stroke prevention, BP lowering therapy should be initiated;

– Several days after stroke

– Immediately after TIA

– Cut off BP for treatment initiation – 140/90 mmHg

– BP Goal – generally 130/80

– Patients with lacunar stroke – SBP <130 mmHg

– Patients with intracranial artery stenosis – SBP <140 mmHg

Choice of Antihypertensive for stroke prevention includes

– ACEI or ARB

– CCB

– Thiazide diuretics

References

Bath. PM, Appleton. JP, Krishnan. K, Sprigg. N (2018). Blood Pressure in Acute Stroke To Treat or Not to Treat: That Is Still the Question. Stroke

Becske. T, Lutsep. HL (2018). Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1164341assessed on 5ht Feb 2019

Bonovish. DC, Hypertension and hypertensive encephalopathy. https://books.google.com.mm>booksassessed on 10th February 2019

Brown. M, Demaerschalk. BM, Hoh. B, Jauch. EC, Kidwell. CS, Mazwi. TML, Ovbiagele. B, Scott. PA, Sheth. KN, Southerland. AM, Summers. DV, Tirschwell. DL (2018). Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke. American Heart Association, Inc

Connolly. ES, Rabinstein. AA, Carhuapoma. JR, Derdeyn. CP, Dion. J, Higashida. RT, Hoh. BL, Kirkness. CJ, Naidech. AM, Ogilvy. CS, Patel. AB, Thompson. BG, Vespa. P (2012). AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Dastur. CK, Yu. W (2017). Current management of spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Stroke and Vascular Neurology; 2:e000047. doi:10.1136/svn-2016-000047.

Hemphill. JC, Greenberg. SM, Anderson. CS, Becker. K, Bendok. BR, Cushman. M, Fung. GL, Goldstein. JN, Macdonald. RL, Mitchell. PH, Scott. PA, Selim. MH, Woo. D (2015). AHA/ASA Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage Journal of

stroke

Powers. WJ, Rabinstein. AA, Ackerson. T, Adeoye.OM, Bambakidis. NC, Becker. K, Biller. J, Ravenni. R, Jabre. JF, Casiglia. E, Mazza. A (2011). Primary stroke prevention and hypertension treatment: which is the first-line strategy? Neurology International ; 3:12- 45

Tsivgoulis. G, Safouris. A, Kim. DE, Alexandrovb. AV (2018). Recent Advances in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Atherosclerotic Stroke. Journal of Stroke ;20(2):145-166.

Whelton. PK, Carey. CRM, Aronow. WS, Casey. DE, Collins. KJ, Himmelfarb. CD, Palma. SMD, Gidding. S, Jamerson. KA, Jones. DA, Laughlin. FJM, Muntner. P, Ovbiagele. B, Smith. SC, Spencer. CC, Stafford. RS, Taler. SJ, Thomas. RJ, Williams. KA, Williamson. JD, Wright. JT (2017). 2017 Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in adults. Journal of American College of Cardiology; 2397

Williams. B, Mancia. G, Spiering. W, Rosei. EA, Azizi. M, Burnier. M, Clement. DL, Coca. A, Simone. G, Dominiczak. A, Kahan. T, Mahfoud. F, Redon. J, Ruilope. L, Zanchetti. A, Kerins. M, Kjeldsen. SE, Kreutz. R, Laurent. S, Lip. GYH, Manus. RM, Narkiewicz. K, Ruschitzka. F, Schmieder. RE, Shlyakhto. E, Tsioufis. C, Aboyans. V, Desormais. I (2018). 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal; 39, 3021–

3104.

Abbreviation

ACEI Angio-tensin converting Enzyme Inhibitor

ARB Angiotensin receptor blocker CCB Calcium channel blocker

GCS Glasgow Coma Scale

ICH Intra cerebral Haemorrhage

MAP Mean Arterial Pressure

NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

RAA Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone

RCTs Randomized Controlled Trial

Aye Aye Sann 1, Aye Myat Nyein 2, Swe Kyinn3

1Professor, Department of Neurology, University of Medicine-2

2Consultant neurologist, Department of Neurology, University of Medicine-2

3Lecturer, Department of Neurology, University of Medicine-2