For clinicians- general practitioners or specialists- are we facing many trial and errors during insomnia treatment? For patients living with insomnia, are they trapped inside a whirlpool of sleeping pills and symptom recurrences? Insomnia disorders are becoming an increasing component during the practice of both general and specialty medicine.

Insomnia is a major sleep disorder in modern world, effecting both adult and children. In recent rural primary health care survey in USA reported 32% of patients were observed symptoms of insomnia and worldwide prevalence of 10 to 30% 1. Compared with men, women face approximately 60% increase risks for insomnia 2.

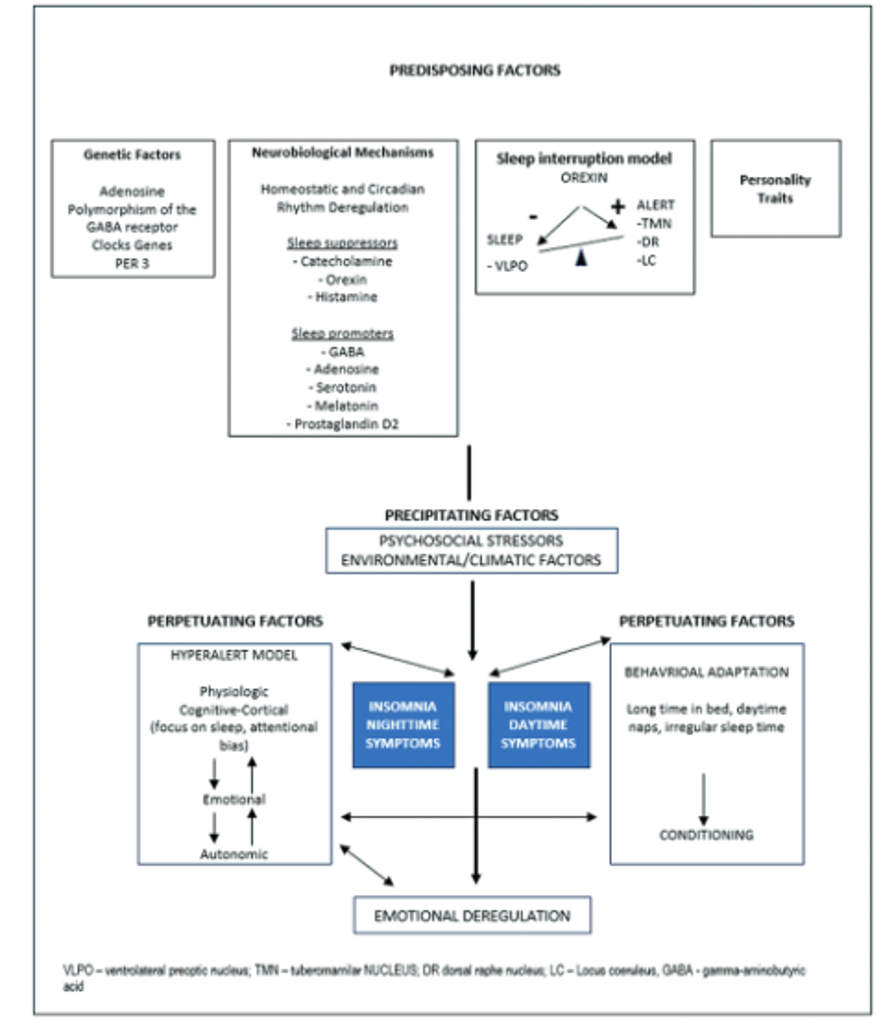

We need to be aware that chronic insomnia patients have “very complex underlying a etiology” (fig. 1) where patients have night time sleeplessness despite a good opportunity to sleep and day time functional impairment including sleep-related quality of life.

Fig.1 Adapted from pathophysiological model of insomnia, Bollu and Kaur and Riemann and colleagues, sleep science, Brazilian sleep association, 2023.

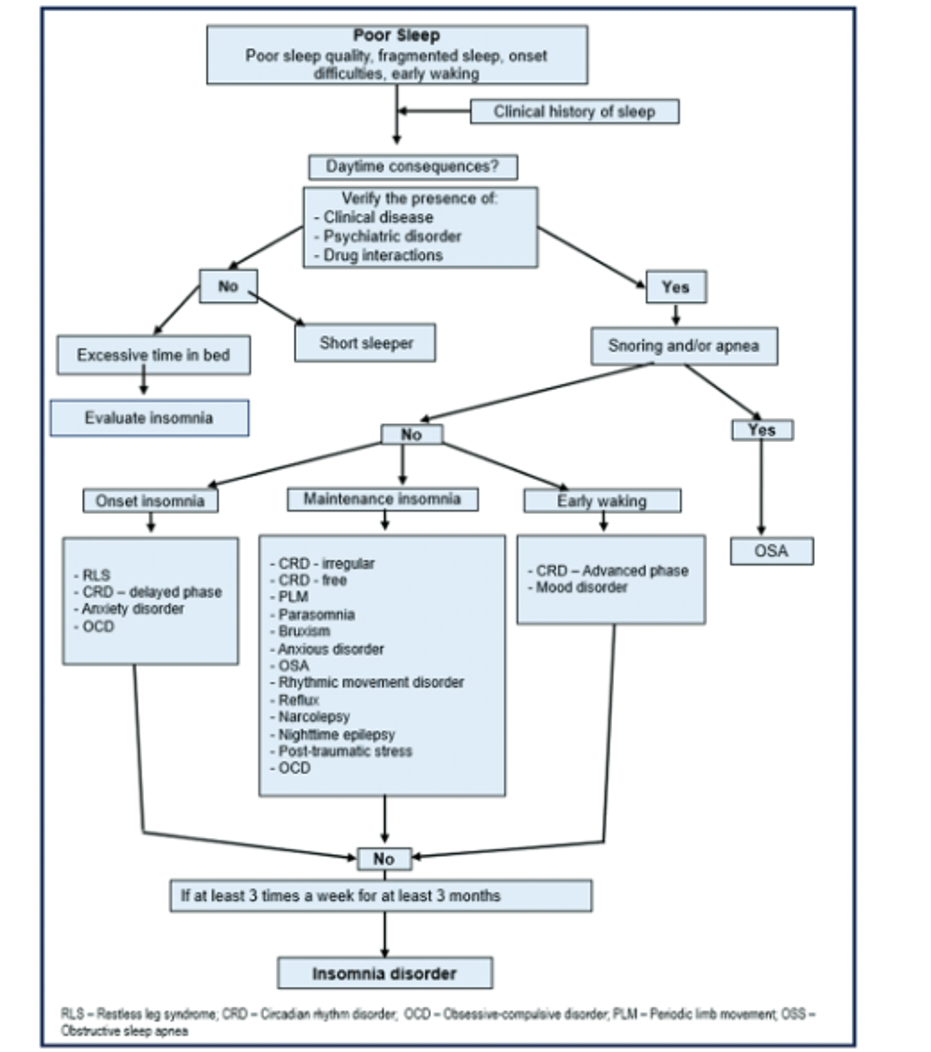

We are talking about chronic insomnia when patient’s symptomatology met with 3 or more times per week and more than 3 months in chronology according to updated ICSD3 (TR)2 or DSM5(TR)3 diagnostic criteria. Insomnia is a clinical diagnosis and no additional diagnostic modalities are required apart from needing to exclude secondary causes when treatment becomes resistant to standard therapy 4. A proposed algorithm for diagnosis and differential diagnosis of chronic insomnia is shown in fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Adapted form differential diagnosis of insomnia, ferre”-Maso and colleagues, sleep science, Brazilian sleep association, 2023.

This disorder has the potential for significant adverse impact on mental and physical health, functioning and quality of life.

To assess insomnia severity and treatment responses, many check lists and question tools are currently in use such as ISI (Insomnia Severity Index), PSQI( Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), CGI(Clinical Global Impression scale), SQOL (Sleep related Quality Of Life) score etc.

For practical management reasons, some organizations define sleep onset insomnia (sleep latency > 20min) and sleep maintenance insomnia (prolong waking after sleep onset), AASM.

What is the first line treatment for chronic insomnia?

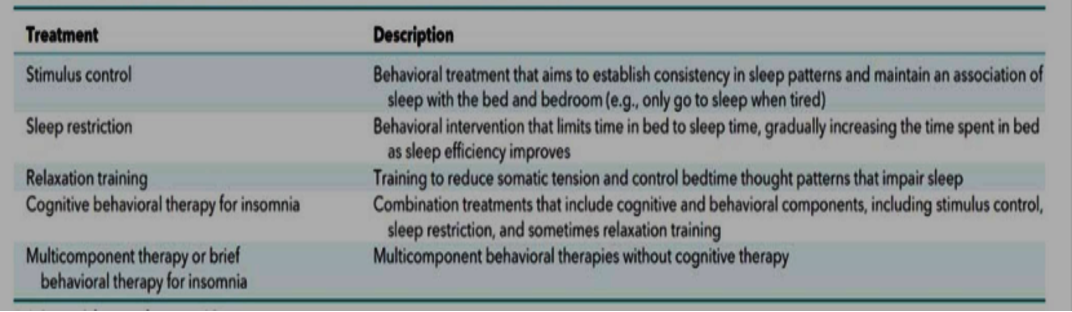

The CBTI (Cognitive and Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia) recommended by AASM 4, ACP 5 and European Insomnia Guidelines is usually used by clinical psychologists and behavioural therapists trained in sleep medicine. Even in developed countries this specialty has resource constraint with uneven ratio of patients to specialists. CBTI has different components for therapy including sleep restriction, stimulus control, cognitive, behavioral, relaxation and sleep hygiene therapies.

The treatment schedules go section by section and takes about 8 to 9 months based on patient compliance. It has now become a group therapy and also practiced online as telemedicine. During the course of treatment, short course of pharmacotherapy is sometime required.

Fig.3 Components of CBTI adapted from annals of internal medicine, ACP journal vol 165, Nov2, 2016

CBTI is considered to have better outcomes than stand-alone pharmacotherapy in terms of patient safety and remission 4. But there is a limitation in numbers of practicing certified therapists and has an effect on worldwide implementation of this intervention. Some experts also raise questions about long-term outcomes after completing the full therapy.

Data on CBTI success rate; showed up to 50-60% of patients attain clinically significant improvement in sleep latency, total sleep time, duration of wakefulness and sleep quality7.

Combined therapy with both CBTI and pharmacotherapy produced higher remission rate than CBTI alone during the 6 months extended follow up trial period (56% vs. 43%)6.

Pharmacotherapy for chronic insomnia

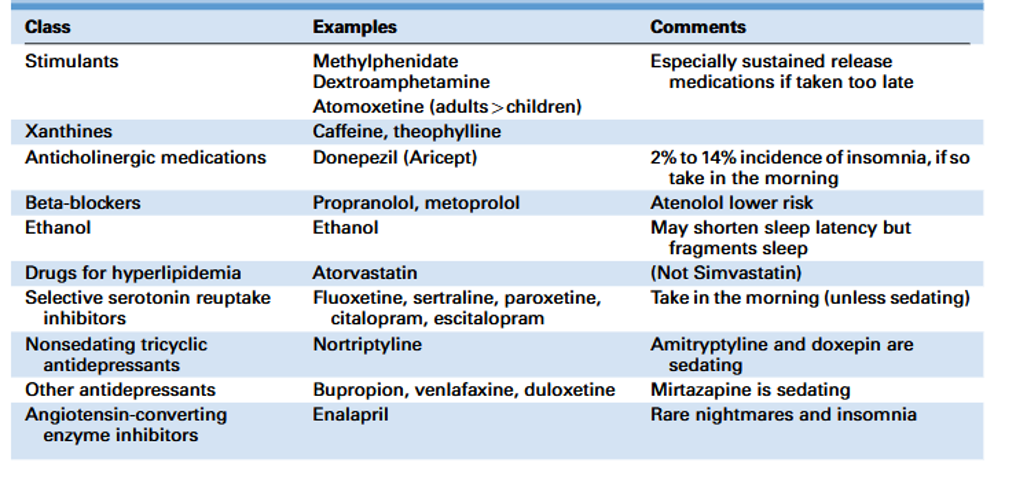

Before recommending that patients continue use of insomnia medications, clinicians should consider treatable secondary causes of insomnia such as depression, pain, BPH, substance abuse, medications including hormones, other comorbid sleep disorders like OSA and restless leg syndrome5. It should also be kept in mind that some medications have effects on sleep architectures and potential for disrupted sleep pattern, (Fig.4)

Fig. 4 adapted from effect of sleep disorders and medication on sleep architectures by Richard B. Berry MD, Mary H. Wagner MD, sleep medicine pearls third edition, 2015.

“Pharmacologic options are considered when CBTI is not available, not effective or not prefer by the patient 4”.

AASM recommendations ; clinical practice guideline for pharmacological treatment of chronic insomnia in adults (2017).

Recommended for treating sleep onset insomnia (difficulty in initiating sleep) (weak recommendation).

1 – Eszopiclone, ramelteon, temazepam, triazolam, zaleplon and zolpidem.

2 – Eszopiclone, zaleplon and zolpidem are BZRA (Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonist, but non benzodiazepine drugs). Studies have indicated BZRA groups can have long term efficacy for 6-12 months without development of tolerance.

3 – Remelteon is synthetic melatonin receptor agonist with 8-10 times more potent then melatonin.

Recommended for treating sleep maintenance insomnia (difficulty in continuity of sleep after sleep onset) (weak recommendation)

1 – Doxepin, eszoclopine, temazepam, suvorexant, zolpedem.

2 – Suvorexant is an orexin (hypocretin) receptor antagonist, a new drug approved for treatment insomnia.

Recommended for sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia (weak recommendation)

1 – doxepin, eszopiclone, temazepam, suvorexant, zolpedem

Not recommended for treating either sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia.

1 – diphenhydramine, melatonin, tiagabine, trazodone, tryptophan, valerian (herbal product).

2 – This is due to small or no improvement of insomnia symptoms compare to placebo and concern of side effects (AASM).

What is the aim of pharmacotherapy for chronic insomnia? (AASM)

1 – Adjunct to CBTI.

2 – To improve sleep quality such as to lower down sleep onset latency (<20 min), to reduce WASO duration (to improve sleep maintenance) and to gain sleep efficiency >86 % (sleep efficiency%= Total Sleep Duration/Total Time in Bed X %).

3 – To improve related day time impairment.

General precautions for using pharmacologic options 7

1 – Start at a low dose and maintain at a lowest effective dose.

2 – Continue nightly use should be avoided, patients should exercise to use only when truly necessary.

3 – Use for >2 -4 weeks should be avoided if possible.

4 – Impairment from hypnotics /sedative can be present despite fully awake.

5 – If the patient has mental depression, anti-depressant may be preferable to a hypnotic.

6 – Hypnotic should be never use with alcohol.

7 – In general pregnancy is a contraindication.

8 – Lower dose should be used in elderly patients.

9 – Benzodiazepines should be avoided in patient with known or suspected OSA.

10 – Rebound insomnia may develop when a hypnotic is abruptly withdrawn.

11 – Rebound insomnia is likely when larger dose with short acting agents.

12 – BZRA drugs should be used with caution in patient with insufficient sleep syndrome (if use together with alcohol) can predispose to parasomnia such as sleep walking and sleep related eating disorders.

13 – Using smaller dosage and tapering the drug gradually can avoid rebound insomnia.

14 – Regular and long term follow up is required to patients with long term pharmacotherapy to check symptom improvement, side effect and dosage adjustment.

Treatment of insomnia in elderly patients7

1 – Multiple factors effect sleep in elderly patients including nocturia, pain syndrome and other comorbidities like CHP, PD, COPD, dementia, stroke, anxiety and depression.

2 – Psychological behavioral intervention are effective in elderly (2008, AASM guidelines).

3 – Drugs tend to have longer duration of effect in elderly patients as a result of changes in metabolism and elimination.

4 – Increased incident of falls and resulting bone fracture when not fully awake or ataxic.

5 – Decrement in day time alertness and performance including increased incidence of motor vehicle accident.

Alternative therapy 7

1 – Accupressure for insomnia (trial)

This is not acupuncture technique but a method of applying pressure to specific body points.

2 – Devices,

Forehead cooling device during sleep said to shorten the sleep stage N1 and N2 (not in standard care).

3 – Diet and exercise

Patients need to avoid alcohol and caffeine at evening. Do not eat heavy meal near bed time.

We have difficulties to practice CBTI due to rarity of this specialty. But, we noted there is no magic pill to treat chronic insomnia and all recommendations are based on individual needs, availability of drugs, safety concern and local regulations. We also need to comply with the current clinical guidelines.

References

1. Clinical practice guidelines for switching or de prescribing hypnotic medications for chronic insomnia, Results of European neuropsychopharmacology and sleep expert consensus group, Sleep Medicine vol.128, April 2024, page 117-126, https;//www. sciencedirect.com/science/articles/pii/s1389v5125000.

2. New England Journal evid, 2024;3(10) published September24,2024.

3. Chronic Insomnia Disorder, page -21 from ICSD3, International Classification of Sleep Disorders and Diagnostic Manual 3 rd edition by American Academy of Sleep Medicine, published in year 2014.

4. Insomnia Disorders, page -409 from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (Text Revision), DSM5 TR, published in year 2022.

5. Management of chronic insomnia in adult, A Clinical Practice Guideline, https://acp journals. org/doi/10.7326/M15-217

6. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the treatment of chronic insomnia in adults, Journal of clinical sleep medicine, vol, 13, No.2, 2017, http://dx.org/10.5664/jcsm6470.

7. Management of Insomnia, Medscape.com, updated on Feb 25, 2025.

Author Information

Zay Ya Aye

MBBS, MMed, Sc. Internal Medicine