Management Of Adult Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes is a complex, chronic illness requiring continuous medical care with multifactorial risk-reduction strategies beyond glycemic control. The aims of management of diabetes are to improve symptoms of hyperglycaemia and minimise the risks of long-term microvascular and macrovascular complications.

Screening for Diabetes (3)

Universal screening program is not recommended. Testing for prediabetes and/or type 2 diabetes in asymptomatic people should be considered in adults of any age with overweight or obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 or ≥ 23 kg/m2 in Asian-Americans) and who have one or more additional risk factors for diabetes as follow:

- First degree relative with diabetes

- Women who were diagnosed with gestational diabetes

- African-American, Native American, Latino, Asian American, Pacific Islander

- Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance: severe obesity, acanthosis nigricans

- History of cardiovascular disease

- Polycystic Ovarian Disease

- HDL cholesterol level <35 mg/dL (0.90 mmol/L) and/or a triglyceride level >250 mg/dL (2.82 mmol/L)

- Hypertension > 140/90 mmHg or on therapy

- Physical inactivity

- A1C >5.7%, Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) or Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG) on previous testing

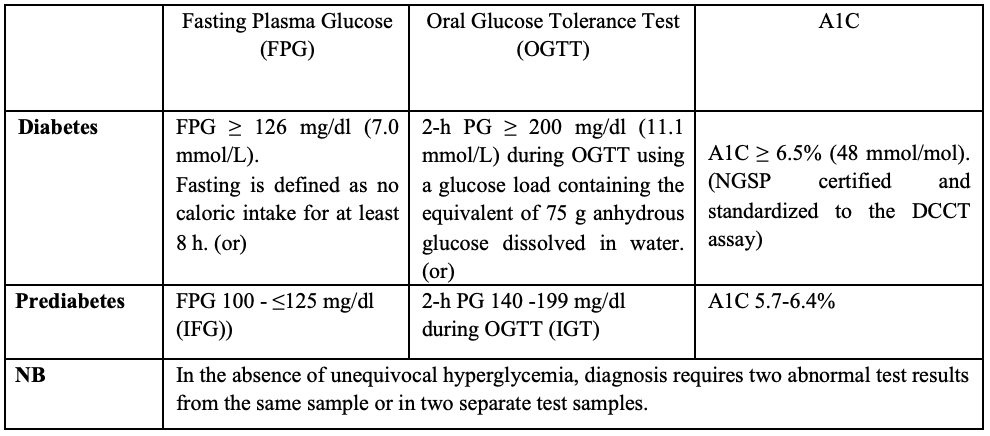

Diagnostic criteria for Diabetes and Prediabetes (4)

Classification of diabetes

Following the identification of hyperglycaemia and subsequent diagnosis of diabetes, etiology of diabetes should be evaluated for determination of subsequent diabetes treatment.

- Type 1 diabetes

- Type 2 diabetes

- Other specific types of diabetes (due to other causes, e.g. genetic defects in B-cell function, genetic defects in insulin action, disease of the exocrine pancreas (pancreatitis, pancreatectomy), drug or chemically induced (such as with glucocorticoid use in the treatment of HIV or after organ transplantation).

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not clearly overt diabetes prior to gestation)

Type 1 diabetes should be considered in a non-overweight patient with no family history of diabetes, positive GAD/IA-2 antibody and low C-peptide. On the other hand, type 2 diabetes patients are usually obese or overweight, aged over 40, presence of family history of diabetes, and high diabetes risk of ethnicity. The causes of other specific types of diabetes should also be sought out (13).

History taking and physical examination

At the initial visit, history taking should be emphasized in detailed history of diabetes if previously known, family history of diabetes, personal history of complications (microvascular and macrovascular, hypoglycaemia, infections) and common comorbidities, lifestyle factors, medications and vaccinations, behavioral and diabetes self-management skills.

Regarding physical examination at initial visit, all patients should be performed recording of BMI (waist circumference, optional) and BP (orthostatic BP when indicated), thyroid examination, diabetic retinal screening (refer to ophthalmologist), comprehensive foot examination (10-g monofilament test and ankle reflex, vibration test, pedal pulses palpation, and ABI when indicated)(4).

Laboratory evaluation

The following investigations should be done at the initial visit:

- If not performed within past 3 months – A1C

- If not performed within the past year

– lipid profile (preferably fasting)

– Serum creatinine and eGFR

– Spot urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR)

– Serum potassium

– Liver function test (optional)

– TSH (optional) (3)

– Resting ECG (2).

Glycaemic targets and monitoring

A1C: Glycemic management is primarily assessed with the A1C test, performed at least twice a year in patients who are meeting treatment goals and quarterly in patients whose therapy has changed or who are not meeting glycemic goals. The A1C goal for patients in general is <7% without significant hypoglycemia. The A1C goal should be individualized based on numerous factors, such as age, life expectancy, comorbid conditions, duration of diabetes, risk of hypoglycemia or adverse consequences from hypoglycemia, patient motivation, and adherence (6). There are some limitations in measuring A1C such as haemoglobinopathies, severe anaemia of any cause.

Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG): Postprandial glucose should be targeted if A1C goals are not met despite reaching pre-prandial glucose goals. SMBG may help with self-management and medication adjustment, particularly in individuals taking insulin.

Pre-prandial plasma glucose = 80–130 mg/dl (4.4–7.2 mmol/l)

2-h Postprandial plasma glucose = <180 mg/dl (<10.0 mmol/l)

Continuous Glucose Monitoring (CGM): CGM has emerged as a complementary method for the assessment of glucose levels with the advent of new technology and are suggested to provide for a much more personalized diabetes management plan.

Management of diabetes

After exclusion of diabetic emergencies, treatment methods for diabetes include dietary/lifestyle modification, oral antidiabetic drugs and injected therapies.

(A) Dietary/ lifestyle modification

All people with diabetes need to pay special attention to their diet. There is not a “one-size-fits-all” eating pattern for individuals with diabetes, and meal planning should be individualized. Medical Nutrition Therapy (MNT) plays an integral role in overall diabetes management, and each person with diabetes should be actively engaged in education, self-management, and treatment planning with the caring doctor.

As for micronutrients and supplements, there is still no clear evidence of benefit from herbal or non-herbal (i.e., vitamin or mineral) supplementation for people with diabetes without underlying deficiencies.

Moderate alcohol intake does not have major detrimental effects on long-term blood glucose management in people with diabetes (4).

Management and reduction of weight is important for people with overweight or obese diabetes. Weight loss can be achieved through healthy diet, physical activity, pharmacotherapy for obesity and bariatric surgery (13).

All patients with diabetes should be advised to achieve a significant level of physical activity and to maintain this in the long term. People with diabetes should perform aerobic and resistance exercise regularly (Aerobic activity bouts should ideally last at least 10 min, with the goal of ~ 30 min/day or more, most days of the week for adults with type 2 diabetes). Flexibility training and balance training are recommended 2–3times/week for older adults with diabetes. Yoga and tai chi may be included based on individual preferences to increase flexibility, muscular strength, and balance (4).

(B) Glucose-lowering medications

ADA/EASD (2019) recommends a patient-centered approach to choosing appropriate pharmacologic treatment of blood glucose. This includes consideration of efficacy and key patient factors:

- important comorbidities such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and indicators of high ASCVD risk, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and heart failure (HF)

- hypoglycemia risk,

- effects on body weight,

- side effects,

- cost, and

- patients‘preferences(4).

Metformin, classically considered as an ‘insulin sensitiser’, reduces A1C by about 1.5% and it has established benefits in microvascular disease in the UKPDS. Metformin in combination with lifestyle modifications should be started at the time type 2 diabetes is diagnosed unless there are contraindications (eGFR< 30 mL/min/1.73m2, acidosis, hypoxia, dehydration, symptomatic heart failure, significantly impaired hepatic function). Once initiated, metformin shouldbe continued as long as it is tolerated and not contraindicated (caution to decline of eGFR).

Metformin is usually introduced at low dose (preferably single daily dose) with or after meals to minimize the risk of gastrointestinal side-effects and its maximum daily dose is 2g. There is a modified-release formulation of metformin, which may be better tolerated by patients with gastrointestinal side-effects(11).Side-effects of metformin include gastrointestinal upset (diarrhea, abdominal cramping, nausea), vitamin B12 deficiency (on long term treatment), risk of lactic acidosis (rare). Metformin can be used in pregnancy but there is no long term data. Metformin may be used in pre-exiting diabetes during lactation.

If the A1C target is not achieved after approximately 3 months, metformin can be combined with any one of the preferred six treatment options: sulfonylurea, thiazolidinedione, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, sodium glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA), or basal insulin. The choice of medication added to metformin is based on the presence of established ASCVD or indicators of high ASCVD risk, other comorbidities, and risk for specific adverse drug effects, as well as safety, tolerability, and cost (4).

Sulphonylureas (SUs) are ‘insulin secretagogues’ with an average A1C reduction of 0.4- 1.6% and are often used as an add-on to metformin if the cost is a major issue. Similar to metformin, the long-term benefits of SUs in lowering microvascular complications of diabetes were established in the UKPDS (13). Its main side-effects are weight gain and hypoglycaemia but second generation SUs (gliclazide, glimepiride) cause less risk of hypoglycaemia and less weight gain. SUs should be taken 30 minutes before meals and dose titration is needed if renal impairment develops.

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are also known as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR- ϒ) agonists and increase insulin sensitivity. They have relatively higher A1C efficacy by reduction of 0.5-1.4%. Pioglitazone appears more effective in insulin-resistant patients. In addition, it has a beneficial effect in reducing fatty liver and NASH (13). Pioglitazone may confer ASCVD benefits (5,9,10). They have rare hypoglycaemia but may exacerbate cardiac failure by causing fluid retention, and recent data show that it increases the risk of bone fracture and possibly bladder cancer.

The ‘gliptins’ or Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors (sitagliptin, vildagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin and alogliptin) inhibits DPP-4 activity, increasing postprandial incretins (glucagon-like peptide 1/GLP-1, GIP) concentrations which act to potentiate insulin secretion. They are very well tolerated and are weight-neutral. There are cardiovascular outcome studies pointing out mixed results with the DPP-4 inhibitors. In general, they have been shown to have neutral effects on cardiovascular outcomes. The disadvantages of DPP-4 inhibitors are nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory infections and pancreatitis (rare)(4).The DPP4 inhibitors, except linagliptin, are excreted by the kidneys; therefore, dose adjustments are advisable for patients with renal dysfunction (14).

SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin) areoral medications that reduce plasma glucose by enhancing urinary excretion of glucose, independent of insulin secretion. All SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with a reduction in weight and blood pressure. According to CVOTs and renal outcome trial (CREDENCE), SGLT2 inhibitors have cardiovascular benefit as well as renal benefit in patients with type 2 diabetes with established ASCVD. They are associated with increased risk of mycotic genital infections, necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum or Fournier’s gangrene (rare) and euglycemic DKA. They have limited efficacy in patients with an eGFR<45 mL/min/1.73 m2 (6). Patients with foot ulcers or at high risk for amputation should only be treated with SGLT2 inhibitors after careful shared decision making around risks and benefits with comprehensive education on foot care and amputation prevention(1).

GLP-1 RA have robust A1C-lowering properties, are usually associated with weight loss and lipid and BP reductions and are available in several formulations.They reduce both fasting and postprandial glucose levels by stimulating glucose-dependent insulin secretion and suppressing glucagon secretion. The CVOTs with GLP-1 RA have shown cardiovascular disease benefits of these agents. The risk of hypoglycemia is low and no dose adjustment is required for liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide in CKD. They should be used cautiously in patients with a history of pancreatitis and discontinued if pancreatitis develops (14).

Meglitinides are short acting insulin secretagogues and reduces A1C by 1.0 – 1.2%. They are primarily used to control post prandial hyperglycemia and can be added to other OADs except SUs. Hypoglycemia & weight gain are less risk compared to SUs. Their dose should be reduced in renal impairment with eGFR< 30mL/min/1.73m2. They should be taken within 10 minutes before main meals (4).

α-Glucosidase Inhibitors (AGIs) delay carbohydrate absorption inthe gut by inhibiting disaccharidases and reduce postprandial glucose excursions. In general, AGIs have modest A1C-lowering effects and low risk for hypoglycemia. They are taken with each meal. The main side-effects are flatulence, abdominal bloating and diarrhea (4). Avoid if eGFR< 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

The quick-release sympatholytic dopamine receptor agonist bromocriptine mesylate has modest glucose-lowering property (10). It can cause nausea and orthostasis, but no hypoglycaemia. Bromocriptine mesylate may be associated with reduced cardiovascular event rates (7,8).

Insulin is the most potent anti-hyperglycemic agent. Comprehensive education regarding SMBG, diet, and the avoidance and appropriate treatment of hypoglycemia are critically important in any patient using insulin. Basal insulin alone is the most convenient initial insulin regimen and can be added to metformin and other oral agents. Starting doses can be estimated based on body weight (0.1–0.2 units/kg/day) with individualized titration over days to weeks as needed. In clinical trials, long-acting basal analogs (U-100 glargine or detemir) have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of symptomatic and nocturnal hypoglycemia compared with NPH insulin (11). Intensification of insulin treatment can be done by adding doses of prandial tobasal insulin. Alternatively, in a patient on basal insulin in whom additional prandial coverage isdesired, the regimen can be converted to two doses of a premixed insulin (4).

Concentrated Insulin (U-200,U-300, U-500 insulin) are invented and have more prolonged and stable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics than U-100 insulin. This may be more convenient for patients in those with insulin resistance who require large doses of insulin (4).

(C) Other Treatment Modalities

In parallel with treatment of diabetes, other risk factors and complications of diabetes need to be addressed, including treatment of hypertension and dyslipidaemia and advice on smoking cessation (13).

(D) Continuing care

Patients with Type 2 diabetes should have an initial dilated and comprehensive eye examination shortly after the diagnosis of diabetes. Subsequent examinations should be repeated annually (13).

Consider referral to a nephrologist whenthere is uncertainty about the etiology of kidney disease, for difficult management issues (anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, metabolic bone disease, resistant hypertension, or electrolyte disturbances), or when there is advanced kidney disease (eGFR<30 mL/min/1.73 m2) requiring discussion of renal replacement therapy for ESRD (12).

The feet of people with diabetes should be screened annually guiding appropriate referral and monitoring. Educate the patients regarding risk and prevention of diabetic foot (13).

Management of diabetes under special situations (Ramadan, old age, pregnancy) are differed from usual diabetes management and all diabetes patients should be educated about hypoglycaemia and sick days rule.

References

- Buse, J. B., Wexler, D. J., Tsapas, A., Rossing, P., Mingrone, G., Mathieu, C., D’Alessio, D. A., and Davies, M. J. (2020) 2019 Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by theAmerican Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 43. pp: 487–493. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci19-0066

- Cosentino, F., Grant, P. J., Aboyans, V., Bailey, C. J., Ceriello, A., Delgado, V., Federici, M., Filippatos, G., Grobbee, D. E., Hansen, T. B., Huikuri, H. V., Johansson, I., Ju¨ni, P., Lettino, M., Marx, N., Mellbin, L. G., Östgren, C. J., Rocca, B., Roffi , M., Sattar, N., Seferovic, P. M., Sousa-Uva, M., Valensi, P., Wheeler, D. C. (2019) 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. The Task Force for diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). European Heart Journal. 00. pp: 1– 69. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486

- Defronzo, R. A. (2011) Bromocriptine: a sympatholytic, D2-dopamine agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 34. pp: 789-794.

- Diabetes Care (2020);43(Suppl. 1):S1–S2 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc20-SINT

- Dormandy, J. A., Charbonnel, B., Eckland, D. J. A., et al. (2005) Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspectivepioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet.366. pp: 1279-1289.

- Garber, A. J., Handelsman, Y., Abrahamson, M. J., Barzilay, J. I., Blonde, L., Bush, M. A., DeFronzo, R. A., Garber, J. R., Garvey, W. T., Hirsch, I. B., Jellinger, P. S., McGill, J. B., Mechanick, J. I., Perreault, L., Rosenblit, P. D. (2020) CONSENSUS STATEMENT BY THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OFENDOCRINOLOGY ON THE COMPREHENSIVE TYPE 2 DIABETES MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM – 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.Endocrine Practice. 26(No. 1). Pp: 107 – 139.

- Gaziano, J. M., Cincotta, A. H., O’Connor, C. M., et al. (2010) Randomized clinical trial of quick-release bromocriptine among patients with type 2 diabetes on overall safety and cardiovascular outcomes. Diabetes Care. 33. pp: 1503-1508.

- Gaziano, J. M., Cincotta, A. H., Vinik, A., Blonde, L., Bohannon, N., Scranton, R. (2012) Effect of bromocriptine-QR (a quick-release formulation of bromocriptinemesylate) on major adverse cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes subjects. J Am Heart Assoc. 1:e002279.

- Kernan, W. N., Viscoli, C. M., Furie, K. L., et al. (2016) Pioglitazone after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med.374. pp: 1321-1331.

- Lincoff, A. M., Wolski, K., Nicholls, S. J., Nissen, S. E. (2007) Pioglitazone and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 298. pp: 1180-1188.

- Monami, M., Marchionni, N., Mannucci, E. (2008) Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH human insulin in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res ClinPract. 81. pp: 184–189.

- National Kidney Foundation. (2013) KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int .Suppl; 3.pp: 1–150

- Pearson, E. R., and McCrimmon, R. J. (2018) Diabetes Mellitus. In: Ralston, S. H., Penman, I. D., Strachan, M. W. J., Hobson, R. P. (ed.) Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 23rd edition. China. Elsevier. pp. 719 – 762.

- Samson, S., and Umpierrez, J. E. (2020)Diabetes Management Algorithm, EndocrPract. 26(No. 1)