Summary

A 25-year-old lady was referred for the evaluation of chronic cough and breathlessness. Since childhood, her symptoms were recurrent despite repeated courses of antibiotics, cough remedies and bronchodilator medications. During recent years, she became more breathless, cough was troublesome with copious sputum. On clinical examination, she has finger clubbing, normal breath sound with crepitations over both lower chest, apex beat and heart sounds on the right side. She is confirmed to have bronchiectasis after radiological investigations. She also found to have chronic rhinosinusitis and situs inversus when further examinations are conducted, fulfilling the triad of Kartagener syndrome. The defective airway mucociliary function is proven by delayed saccharin transit time. Bronchiectasis, a chronic lung disease due to a rare congenital cause with many clinical consequences is described to heighten awareness, to get early diagnosis and better understanding of its management aspect.

Background

Bronchiectasis is one of the commonly encountered chronic lung diseases that can cause significant morbidities and health care burden, especially in severe diseases. The definitive diagnosis can be delayed, unrecognized, and mistaken with other chronic lung diseases. One of the studies has shown an average delay period between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of 17 years and these patients are often initially labelled as having COPD or asthma before bronchiectasis is suspected. Bronchiectasis should be considered where respiratory tract infections are severe, persistent, unusual, or recurrent. Early suspicion, timely recognition, and subsequent appropriate management can modify the disease progression, reduce its severity, morbidity, and mortality of the patients1. When considering the etiologies behind it, post infectious causes like pulmonary tuberculosis, severe pneumonia and repeated severe childhood respiratory infection are the commonly recognized causes but rare congenital conditions such as primary ciliary dyskinesia or immune deficiency should not be missed.

Case presentation

A 25- year- old woman was referred to the Department of Respiratory Medicine for further evaluation of chronic productive cough. On further questioning, she had repeated episodes of productive cough throughout her childhood and teenage years. During the last five years, she felt breathless more pronounced on exertion as well as chest tightness associated with wheezing on some of the days. She also noticed recurrent episodes of stuffy nose, nose block and nasal discharge, dipping along the throat when lying down. She had no fever, allergies, or skin rash. She had stable body weight with normal appetite. One month prior to recent admission, she coughed up mucopurulent sputum of large volume, about 50 to 100 ml per day (Figure 1). She became more breathless than usual and had hemoptysis one week before admission.

She was seen as an outpatient in the clinics many times and was given repeated courses of antibiotics, cough remedies, bronchodilators but her symptoms were not much improved. She needed hospitalization for more severe episodes and the last admission was due to Klebsiella pneumoniae infection three months ago. According to her mother, she was delivered uneventfully in full term. She has no other medical conditions and is not aware of having infections like measles, whooping cough, tuberculosis in the past. She is a single without menstrual problem. She had struggled to pass the high school education because of her ill health. She lives with her mother and an elder brother who are well without respiratory symptoms. There is no consanguinity marriage in her family. Her home environment is not crowded and there is no pet at home. The whole family does not smoke and drink.

On clinical examination, she was rather thin with BMI 18.5 kg/m2. She was tachypneic and tachycardiac but had no wheezing or fever. BP was normal with SpO2 of 92% on room air. She had finger clubbing, but no lymphadenopathy and pedal oedema. There was vesicular breath sound equal on both lungs with coarse crackles over both lower zones. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. Her apex beat was on the right 5th intercostal space and heart sounds were best heard on the right side of chest.

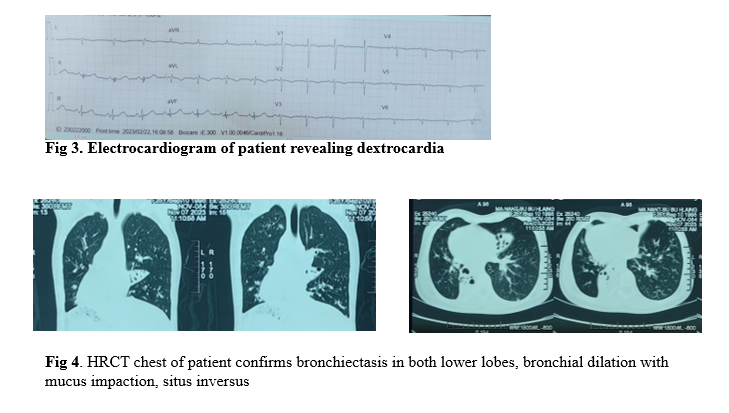

Chest X-ray revealed cardiac apex and aortic arch on right side, right-sided stomach air, with consolidation in left para-cardiac area and thickened bronchial walls in both lower zones (Figure 2). Her blood tests showed an increased total white cell count with neutrophilia, raised CRP and ESR. Liver and renal function were normal. Connective tissue screening test and serology for hepatitis B, C and retroviral infection were non- reactive.

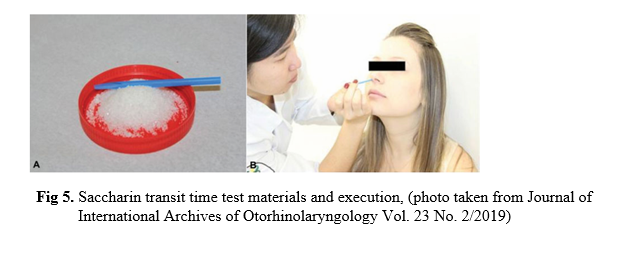

Her initial diagnosis was bronchiectasis exacerbated by lower respiratory tract infection. She was given treatment with empirical IV antibiotics, oxygen therapy, nebulized bronchodilators and mucolytics. Electrocardiogram showed inverted P waves in lead I, right axis deviation and QRS com¬plexes get progressively smaller in leads V 1–V 6 (Figure 3). Ultrasound examination of the abdomen had a normal liver and gall bladder on the left side and a normal spleen on the right side. On further investigations, HRCT chest confirmed bronchiectasis in both lower lobes and situs inversus totalis. There was atelectasis with mucus plugging in lingular segment of right upper lobe and left middle lobe. (figure 4). On reviewing the previous available records, findings of dextrocardia and situs inversus were not noted down.

Flexible bronchoscopy was proceeded to expel mucus plug impaction, to exclude other causes of endobronchial obstruction and to get the lower respiratory samples for microbiology investigations. Mycobacteria infection was excluded by negative results of sputum and bronchial washing samples for AFB stain and Xpert MTB/Rif test. There was heavy growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa on Sputum culture, so antibiotic treatment was tailored according to sensitivity results. Her sinus Xray had opacified both maxillary sinuses and on nasoscope, there was copious mucopus in both nasal passages and postnasal space. She was advised to have nasal douching with nanocare/hypertonic saline solution followed by fluticasone nasal spray for her chronic rhinosinusitis by ENT specialist.

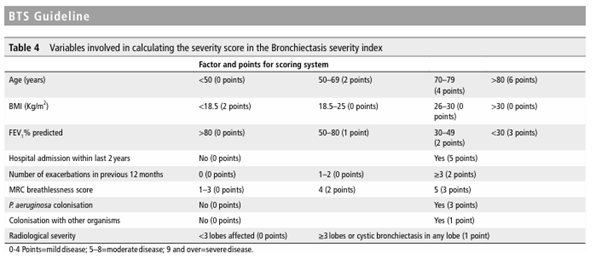

Our patient fulfills diagnostic triad of Kartagener syndrome: chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis, and situs inversus. The nasal mucociliary clearance transit time (MCCTT) was tested at her bed side using saccharin test. The transit time was more than 30 minutes indicating that she had significant mucociliary dysfunction. Spirometry was also performed to find coexisting bronchial asthma and for severity assessment. It showed an obstructive pattern with FEV1 of only 30% predicted which was increase to 12% after post bronchodilator. She also had bilateral conduction defects, on audiometry. She was found to have severe disease on severity assessment by using Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI), to predict the likelihood of complications, mortality, and exacerbations (Table 1).

After completing two weeks course of IV Cefipime 1G 12 hourly, clinical improvement was noted with reduction in sputum volume and purulency. Together with daily chest physiotherapy, airway clearance pharmacotherapy, inhaled bronchodilators, and treatment for chronic sinusitis, she was no longer breathless, no more hypoxic along with improvement of laboratory parameters. Before discharge, the patient was counselled for disease nature, possible complications, and management plan. Infertility, the important aspect that could be associated with Kartagener syndrome; therefore, it was addressed properly for her marriage life. She was also advised for yearly influenza vaccination, healthy lifestyle, physical activity and self-practice of chest physiotherapy, regular follow up to specialists’ outpatient departments. She was discharged with po ciprofloxacin 500 mg BD for two weeks as an eradication treatment of Pseudomonas infection. On the subsequent follow-up visits, the patient was doing well with improved exercise tolerance, better lung function parameters and negative pathogen on sputum surveillance.

Discussion

Bronchiectasis is defined as abnormal chronic dilatation of one or more bronchi. Primary insult is sometimes unknown, but pathological changes in response to Cole’s vicious cycle hypothesis are thought to be responsible for disease progression. The major factors that contribute to the development of bronchiectasis are impaired function of airway mucociliary clearance system and infection. The accumulation of bronchial secretion leads to bacterial overgrowth and colonization in the airways, subsequently results in damage to the integrity of bronchial wall, and this vicious cycle goes on.

Post infectious aetiology is the commonly recognized cause of bronchiectasis in our health care setting but other causes, rare congenital conditions such as primary immune deficiency, primary ciliary dyskinesia, or airway obstruction by impacted foreign body, should also be considered. Investigations such as HRCT, immunoglobulin assays (IgG, IgA, IgM), IgE/precipitin specific to Aspergillus fumigatus, concentrations of nasal nitric oxide, to find out the specific aetiologies, are generally available only at specialist centers2. Referral to secondary care settings is specifically necessary when the diagnosis is doubtful, the underlying aetiology seems to be unusual, need to investigate further and correctable. In those cases, the specialist’s advice for management plan, specific treatment on top of the general treatment, can modify the disease course.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is an autosomal recessive disorder causing ultrastructural defects in the cilia. Normal ciliary function is essential for respiratory host defense, important for motility of sperm/ovum and it also ensures proper visceral orientation during embryogenesis. Kartagener syndrome is a subset of PCD, comprised of the classic triad: situs inversus, bronchiectasis and chronic sinusitis. There is gene mutation at DNAI1 and DNAH5, leads to impaired ciliary motility, which predisposes to recurrent sinopulmonary infections, infertility, and errors with left–right body orientation. Manes Kartagener first recognized this syndrome in 1933, so the syndrome is bearing his name. Its estimated incidence is approximately 1 in 30,000 live births with equal incidence in males and females5.

Diagnosis of Kartagener syndrome can be made by tests to prove impaired cilia function, defective structure, and genetic mutation. The Saccharin test can be used as a screening test at the patient’s bedside to detect abnormal mucociliary clearance in nasal passage (Figure 5). This test measures the time taken for a pellet of saccharin placed on the inferior turbinate to be tasted. In healthy individuals, saccharin transit time does not exceed 20 minutes4. Measuring exhaled nasal nitric oxide involves measurement of the expired nitric oxide from the nostril. Reduction in mucociliary transport can also be measured in situ by administering an inhalation aerosol of colloid albu¬min tagged with 99Tc. Electron microscopy of a nasal or bronchial biopsy can be performed to demonstrate the defective cilia structure. Mutations in the genes DNAI1 and DNAH5 can be done by genetic testing. However, most of the above procedures are available only at specialized centers. Therefore, the diagnosis of Kartagener syndrome is clinical and supported by imaging studies in most settings.

The commonest symptoms of bronchiectasis are chronic cough and sputum production, and the clinical course is varied with intermittent exacerbations. An exacerbation

can be recognized by the presence of three or more factors: deterioration in cough and sputum volume or purulency for at least 48 hours; worsening breathlessness or exercise intolerance; or a change in bronchiectasis treatment is needed.

The goals of treatment for bronchiectasis patients are reduction of symptoms, overall morbidity, mortality, and improvement in quality of life and preservation of lung function1. The pharmacological treatment options of bronchiectasis include antibiotics, airway pharmacotherapy, and inhaled bronchodilators. Antibiotic treatment in bronchiectasis also ranges from oral or IV antibiotics to inhaled antibiotics and long‑term antibiotic therapy depending on the pathogens, disease severity and patient factors. Vaccination against respiratory infections such as influenza and pneumococcus are also necessary as preventive aspect.

Proper chest physiotherapy including active cycle breathing techniques, postural drainage is equally important treatment option to pharmacotherapy. Pulmonary rehabilitation could improve the quality of life and exercise capacity in these patients3. Surgical excision can be considered in localized disease with the risk for repeated infection or bleeding. Patients usually need life‐long treatment, so educating the patients, providing information and psychological support is often required. Regarding the management of Kartagener syndrome, as it has no definite treatment to cure the disease, genetic counseling and fertility issues should be addressed on top of principles and management of bronchiectasis in general5. Early recognition of the disease, multidisciplinary approach in treatment and follow-up at regular intervals are also essential.

To better predict the consequences of bronchiectasis: Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI) and FACED score have been developed and validated in different cohorts of patients2 (Table 1). Approximately one third of enrolled patients to United States Bronchiectasis Research Registry was found to have sputum culture that was positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Colonization of airway with P. aeruginosa has been shown to cause poor outcome of disease: increase frequency of exacerbations, increased mortality, hospital admissions, worse quality of life, and deterioration in lung function3. With this regard, Pseudomonas infection in all bronchiectasis patients should be properly managed according to guidelines.

Take home message

Kartagener syndrome, a subset of primary ciliary dyskinesia, as a rare congenital cause of bronchiectasis is reported here to get the awareness. In primary care settings, when the lower respiratory infections are persistent, or recurrent requiring multiple courses of antibiotics, bronchiectasis should be considered. Bronchiectasis should also be kept in mind as a potential diagnosis when the clinicians are encountering patients with chronic cough, obstructive airway disease, or chronic rhinosinusitis. Early diagnosis of the disease and practice of proper management strategies are essential to modify the disease course, lung function, prognosis, and quality of life in bronchiectasis patients.

Table 1. Bronchiectasis Severity Index (BSI)

References

- European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017; 50: 1700629.

- The BTS Guideline for Bronchiectasis in Adults. Journal of the British Thoracic Society, January 2019.

- O’Donnell, A. E., (2022) Bronchiectasis -A Clinical Review. N Engl J Med. 2022; 387:533-45.

- Rodrigues, F. et al. (2019) Particularities and Clinical Applicability of Saccharin Transit Time Test. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology 2019; 23:229–240.

- Ibrahim, R. & Daood, H. (2021) Kartagener syndrome: A case report. Can J Respir Ther 2021; 57: 44–48.

Author Information

Yin Mon Thant

Professor/Senior Consultant Chest Physician, Department of Respiratory Medicine,

Thingangyun General Hospital