Hypertension in Children

The prevalence of hypertension in children appears to be increasing especially in view of the growing population of children with obesity. However, the true incidence of hypertension in the pediatric population is not known. This vagueness partly stems from the somewhat arbitrary definition of hypertension and is in part related to incomplete blood pressure screening during routine paediatric clinical visits. Recent evidence indicates that childhood blood pressure predicts blood pressure in the adult. It is therefore importance to detect hypertension in childhood.

Best Blood Pressure Measurement Practices

- Blood Pressure may vary considerably between visits and even during the same visit in both children and adults because of factors like anxiety and recent caffeine intake.

- Blood Pressure generally decreases with repeated measurements during a single visit, although the variability may not be large enough to affect blood pressure classification.

- The usual precautions for measuring blood pressure in adults should be taken, but the correct cuff size should be used. The bladder length should be 80%–100% of the circumference of the arm and the width should be at least 40%.

- Blood pressure should be measured on the right arm for consistency for comparison with standard tables and to avoid a falsely low reading from the left arm in the case of coarctation of the aorta. The arm should be at heart level, supported and uncovered above the cuff. The patient and observer should not speak while the measurement is being taken.

- On auscultation, Korotkoff I should be taken as systolic blood pressure and phase V Korotkoff as diastolic blood pressure.

- To measure blood pressure in the legs, the patient should be in the prone position, if possible. An appropriately sized cuff should be placed mid thigh and the stethoscope placed over the popliteal artery. The systolic blood pressure in the legs is usually 10%–20% higher than the brachial artery pressure.

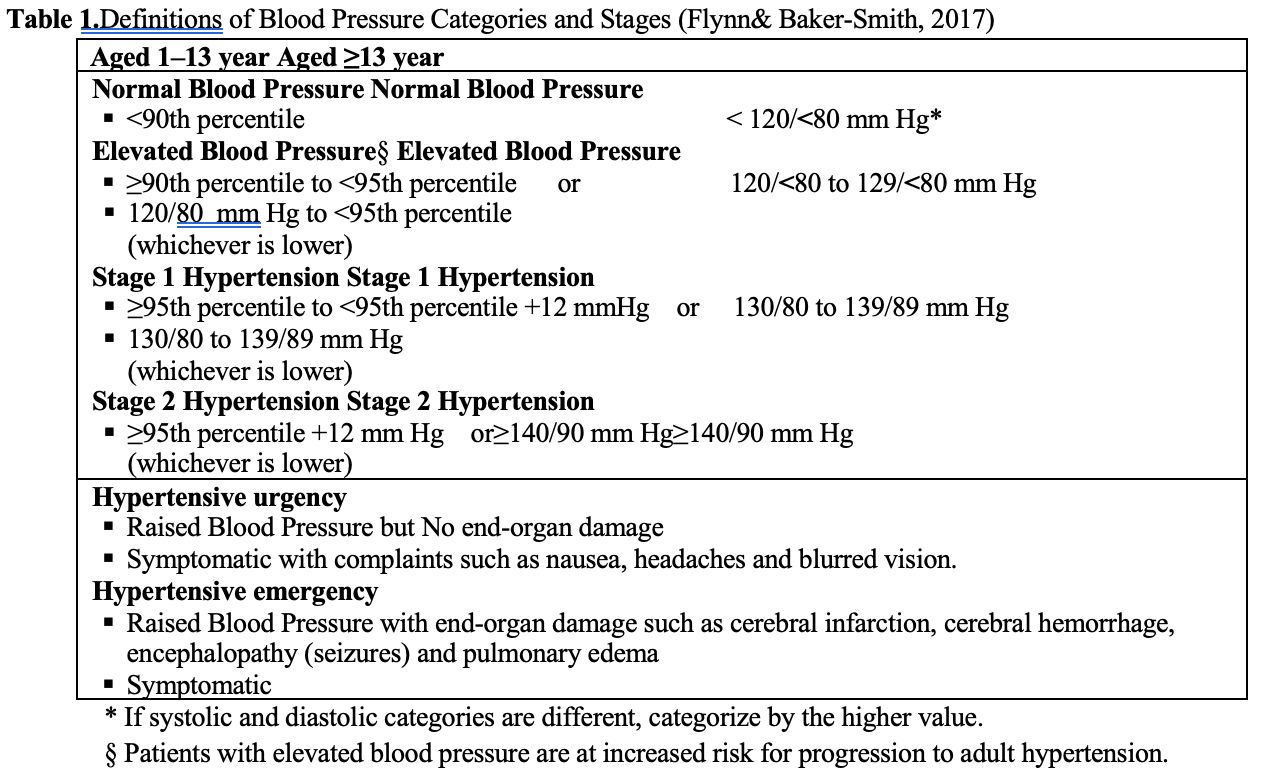

Definition of Hypertension in children

It is clinically defined as elevated blood pressure if systolic and/or diastolic pressure >_ 90th percentile and as hypertension if systolic and/or diastolic pressure >_ 95th percentile for age, sex and height percentile on >_3 separate occasions.

24-Hour Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM)

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) detects blood pressure (BP) changes throughout the 24 hours and is useful in the initial evaluation of elevated BP to recognize subjects at risk, and in evaluating response to treatment. The mean 24-hour BP (systolic and diastolic) are compared with gender and height-specific percentiles-based data. Monitoring of BP on a 24-hour basis may also help in diagnosing so-called “white coat hypertension” which is common in children because they are uncomfortable at the physicians’ office. Use of 24-hour BP monitoring should be considered first in most uncomplicated cases of paediatric stage I hypertension.

Timing of Blood Pressure Measurements

- Children >_3 years should have their blood pressure measured at least once during every health care episode.

- Children <3 years should have their blood pressure measured in the following circumstances:

o History of prematurity, very low birth weight (VLBW),other problems requiring neonatal intensive care

o Congenital heart disease (repaired or non-repaired)

o Recurrent urinary tract infection, hematuria, or proteinuria

o Known renal or urologic disorders

o Family history of congenital renal disease

o Malignancy or Solid organ transplant or bone marrow transplant

o Treatment with drugs known to raise blood pressure

o Systemic diseases associated with hypertension (neurofibromatosis, tuberoussclerosis)

o Elevated intracranial pressure

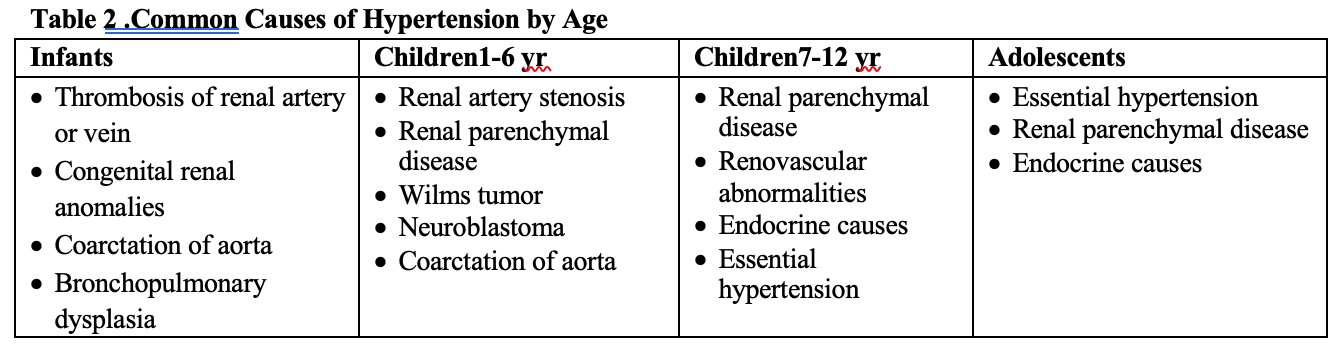

Aetiology

Hypertension can be primary (i.e, “essential”) or “secondary”. In general, the younger the child and the higher the blood pressure, the greater the likelihood that hypertension is secondary to an identifiable cause. A secondary cause of hypertension is most likely to be found before puberty. After puberty, hypertension is likely to be essential.

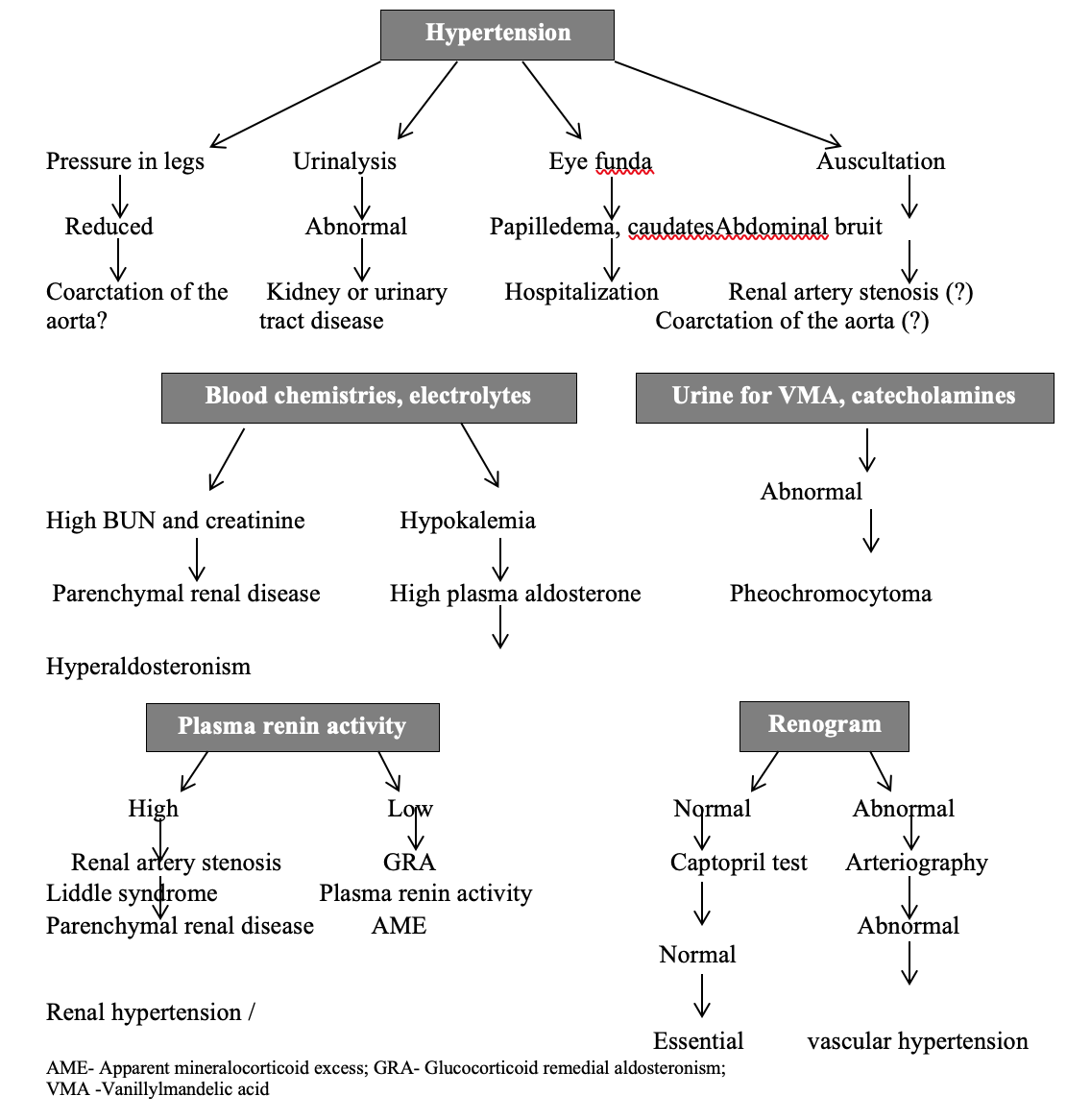

Identification of signs of secondary hypertension

Most young patients with secondary hypertension have a renal parenchymal abnormality. The following should be evaluated to assess for potential causes of hypertension.

- Body mass index may lead to an evaluation for metabolic syndrome

- Tachycardia may indicate hyperthyroidism, pheochromocytoma, and neuroblastoma

- Growth retardation may suggest chronic renal failure

- Café au lait spots may point to neurofibromatosis

- An abdominal mass may lead to an evaluation for Wilms tumor and polycystic kidney disease

- Epigastric or abdominal bruit may lead to the diagnosis of coarctation of the abdominal aorta or renal artery stenosis

- BP difference between the upper and lower extremities indicates coarctation of the thoracic aorta

- Thyromegaly may suggest hyperthyroidism

- Virilization or ambiguity may suggest adrenal hyperplasia

- Stigmata of Bardet-Biedl, von Hippel-Lindau, Williams, or Turner syndromes

- Acanthosis nigricans may indicate metabolic syndrome

Laboratory Studies

Findings from the patient’s history and physical examination dictate the appropriate choice of tests. The complete blood cell (CBC) count may indicate anaemia due to chronic renal disease. Blood chemistry studies may be helpful. An increased serum creatinine concentration indicates renal disease. Hypokalemia suggests hyperaldosteronism.. High plasma renin activity indicates renal vascular hypertension, including coarctation of the aorta, whereas low activity indicates glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism, Liddle syndrome, or apparent mineralocorticoid excess. A high plasma aldosterone concentration is diagnostic of hyperaldosteronism. High values of catecholamines (eg, epinephrine, norepinephrine, or dopamine) are diagnostic of pheochromocytoma or neuroblastoma.

On urine dipstick testing for blood or protein indicates renal disease. Urine cultures are used to evaluate the patient for chronic pyelonephritis. High urinary excretion of catecholamines and catecholamine metabolites (metanephrine) indicates pheochromocytoma or neuroblastoma. Urine sodium levels reflect dietary sodium intake and may be used as a marker to follow a patient after dietary changes are attempted. Fasting lipid panels and oral glucose-tolerance tests are performed to evaluate metabolic syndrome in obese children.

Echocardiography and Ultrasonography

The finding of LVH on echocardiography confirms the chronicity of the hypertension and is an indication to start treatment. Echocardiography is essential in the evaluation of suspected aortic coarctation. Abdominal ultrasonography may reveal tumors or structural anomalies of the kidneys or renal vasculature. Renal scarring suggests excessive renin release. Asymmetry in renal size suggests renal dysplasia or renal artery stenosis. Renal or extra renal masses suggest a Wilms tumor or neuroblastoma, respectively. On Doppler studies, asymmetry in renal artery blood flow suggests renal artery stenosis.

Angiography

Angiography may reveal differences in the structure (diameter) of the renal vessels. Sampling of blood from renal arteries, renal veins, and aorta may reveal differences in renin secretion between the kidneys. A renin activity ratio of 3:1 between the kidneys is considered diagnostic of renal vascular hypertension.

Other Tests

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography can provide further anatomic definition of aortic coarctation, renal stenosis and abdominal tumours. Radionuclide imaging may be considered, with or without captopril; asymmetry suggests renal artery stenosis. Polysomnography helps in identifying sleep disorders associated with hypertension. This test should be considered in obese children with a history of snoring, daytime sleepiness, or any sleep difficulties

Approach Considerations

To the extent possible, treatment of hypertension should address the cause and correct it. It is essential to recognize remediable causes of hypertension, especially coarctation of the aorta in a symptomatic infant. Reserve the therapeutic modalities for those children who have irremediable causes of hypertension or essential hypertension.

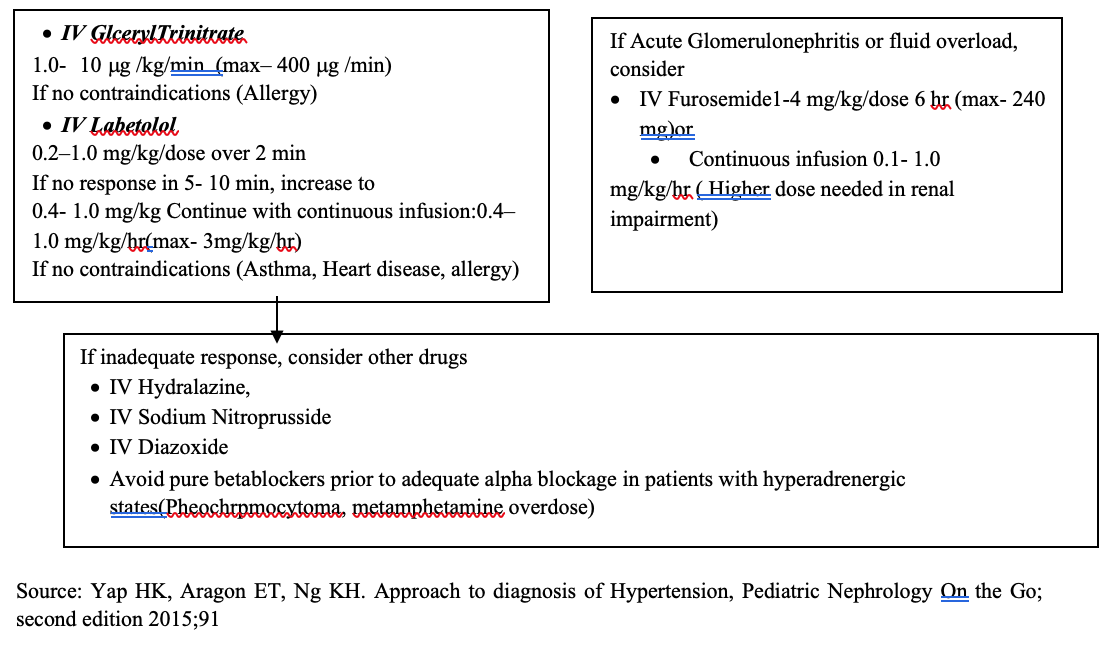

The role of GPs

The General Practitioner, being the first point of contact with the patient, needs to be aware of the extent of disease burden in children. Early diagnosis, referral and treatment are valuable in preventing progression into adult hypertension. Once in the care of specialists, management will be instituted as Nonpharmacologic Therapy including weight reduction & stress release, exercise, potassium supplementation, salt restriction and/or pharmacologic therapy, the goal of which should be a BP below the 90th percentile. If BP is not controlled, a drug from another class should be added. If control is still not achieved, reconsider the possibility of secondary hypertension before adding a third drug. Should hypertensive crises occur (cerebral edema, seizures, heart failure, pulmonary edema, or renal failure) as a result of an acute illness (e.g, post infectious glomerulonephritis or acute renal failure), excessive ingestion of drugs or psychogenic substances, or exacerbated moderate hypertension, select an agent with (a) rapid and predictable onset of action (b) minimal CNS side effects (to prevent masking of signs related to hypertensive encephalopathy). The IV route is preferred as fall in pressure can be carefully titrated. Conditions that may mimic hypertensive emergency e.g intracranial pathology, seizures must be excluded. Stepwise reduction should be planned as too rapid reduction may interfere with adequate organ perfusion. In general, blood pressure should be reduced by about 1/3 of total planned reduction during 1st 12 hours and next 1/3 over 12 hours and final 1/3 over 24 hours.

Selecting for long term use

To use drugs that preferably can be used once daily, maximizing treatment dosage before adding a further drug. The agents used will come from the following ‘ABCD’ groups:

- ACE –inhibitor and (Angiotensin-II receptor blockers)ARBs ( for high renin essential hypertension and high renin due to renal or renovascular diseases)

- Beta blocker

- Calcium channel blocker

- Diuretics (For volume dependent hypertension)

Children generally respond better to drugs that block the renin system. These include ‘A’ drugs and ‘B’ drugs. If more than one drug is required, to combine ‘A’ or ‘B’ with ‘C’ or ‘D’ .It is not logical to combine A with B or C with D. If hypertension is still not well controlled, triple therapy; A+C+D or B+C+D should be given. For infants: Use shorter acting agents for flexibility of dosage; propranolol instead of atenolol, captopril instead of enalapril. Once stable, patient may be changed to the longer acting antihypertensives.

References

- Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for Screening and Management of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171904

- Johnson WH, Moller JH; Pediatric Cardiology, The Essential Pocket Guide, 3rd edition, Wiley Blackwell, (2014).

- Mattoo, TK . Definition and diagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents, updated: May 13, 2019. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/definition-and-diagnosis-of-hypertension-in-children-and-adolescents

- Pastel NH , Romero SK, Kaelber DC. Evaluation and management of pediatric hypertensive crises: hypertensive urgency and hypertensive emergencies. Open Access Emergency Medicine 2012:4 85-92.

- Rees L, Webb NJA, Brogan PA; Paediatric Nephrology, Oxford University Press, 1stEdition ,2007; 334-341.

- Rodriguez-Cruz E. Pediatric hypertension,emedicine, Updated: Mar 09, 2017:https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/889877

- Yap HK, Ng KH Resontoc LPR. Treatment of Hypertension, Pediatric Nephrology On the Go; second edition 2015;51-91

Khin Maung Oo M.B.,B.S ,M. Med. Sc (Paed:),M.R.C.P.C.H(U.K), F.R.C.P (Edin:), F.As.C.C Paediatric Cardiologist/Interventionist, Yankin Children’s Hospital, Yangon