Nandar Min Swe

Low Bone Mass

Low bone mass (osteopenia) based on bone mineral density (BMD) criteria is defined as a T-score between -1.0 and -2.5.

In postmenopausal women with low bone mass who have not experienced a fragility fracture, absolute fracture risk is calculated using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX).

High estimated fracture risk – Patients with prior fragility fracture or high estimated fracture risk (eg, 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture ≥20 percent or 10-year probability of hip fracture ≥3 percent) are considered to have osteoporosis.

Low to moderate estimated fracture risk – For patients with low to moderate fracture risk (eg, 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture <20 percent and 10-year probability of hip fracture <3 percent), we typically do not use pharmacologic therapy to prevent bone loss or fracture1. Management decisions should be individualized based on patient preferences and the expected benefits and potential risks of drug therapy. For example, initiating pharmacotherapy may be reasonable in the following settings :

- The patient wishes to prevent or attenuate the accelerated bone loss that occurs around the time of menopause.

- The patient has low bone mass and at least one other clinical risk factor for fracture

Table 1

Options for pharmacotherapy — If a decision is made to initiate pharmacologic therapy, we typically select a bisphosphonate (table 2).

Table 2. Available FDA-approved medications for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women

Choice of bisphosphonate – The choice of bisphosphonate is largely guided by patient preference and formulary restrictions.

Oral bisphosphonates – We prefer weekly alendronate or risedronate to other oral bisphosphonates because of their efficacy, favorable cost, and the availability of long-term safety data. Limitations of oral bisphosphonates include the complex dosing regimen and poor long-term adherence to therapy.

In postmenopausal women without osteoporosis, alendronate 2-6, risedronate 7-9, and ibandronate 10, prevent bone loss, but trial data have not established a reduction in fracture risk.

Zoledronic acid – For women unable to take oral bisphosphonate therapy due to intolerance or a contraindication, intravenous (IV) zoledronic acid is a reasonable alternative. Some patients also may prefer zoledronic acid for greater convenience.

If zoledronic acid is selected, ≥2 doses should generally be administered. We reevaluate the patient two years after the initial dose to determine the timing of subsequent dosing. In the United States, zoledronic acid (administered every two years) has regulatory approval for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with low bone mass 11.

Alternative therapies

Raloxifene – We prefer raloxifene to other selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) because it has eight-year safety and efficacy data and reduces the risk of breast cancer. Raloxifene inhibits bone resorption and reduces the risk of vertebral fracture. Raloxifene also increases thromboembolic events and hot flashes and has no apparent effect on heart disease or the endometrium.

Bazedoxifene, another SERM, is available in Europe and Japan for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. In the United States, it is available in combination with conjugated estrogen for prevention of osteoporosis 12.

Menopausal hormone therapy – Although we do not consider estrogen-based hormone therapy a first-line option for fracture prevention, women who initiate treatment for menopausal symptoms will have reduced risk of bone loss and fracture 13-16. We typically start women on a transdermal estradiol preparation, which imparts beneficial skeletal effects at doses as low as 0.014 mg/day17-19.

Osteoporosis

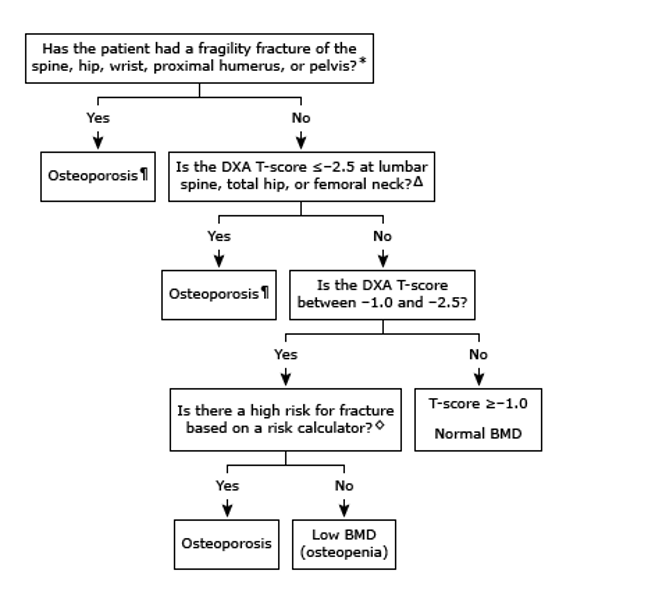

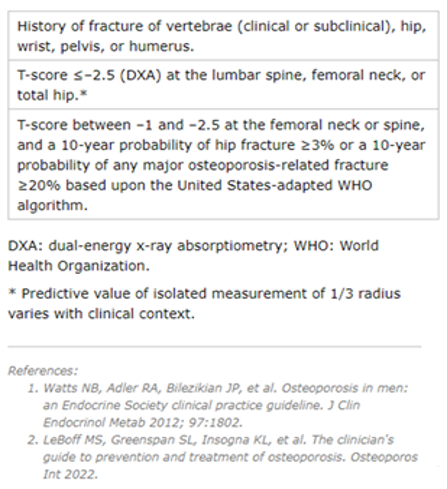

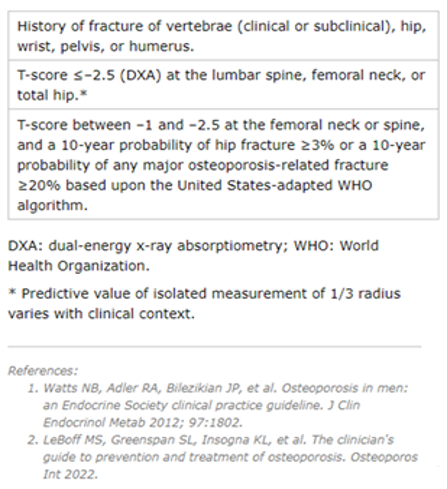

Osteoporosis may be diagnosed based on history of fragility fracture, BMD, or calculated 10-year fracture risk.

Fig.1 Diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women

https://www.fraxplus.org

Patient selection — Our approach to initial osteoporosis pharmacotherapy is largely in agreement with the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF, formerly the National Osteoporosis Foundation [NOF]) recommendations, which apply to postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years (table 3) 20

These recommendations are widely accepted and supported by clinical trial data on fracture prevention.

Table 3. Guidelines for pharmacologic intervention in postmenopausal females and males > 50 years of age

We recommend pharmacologic therapy for postmenopausal women with a history of fragility fracture or with osteoporosis based upon bone mineral density (BMD) measurement (T-score ≤-2.5). Particular attention should be paid to treating women with a recent fracture, including hip fracture, because they are at high risk for a second fracture 21-22

We also suggest pharmacologic therapy for high-risk postmenopausal women with T-scores between -1.0 and -2.5. We calculate fracture risk using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (https://www.fraxplus.org). In the United States, a reasonable threshold to define high risk is a 10-year probability of hip fracture or combined major osteoporotic fracture of ≥3 or ≥20 percent, respectively.

Choice of initial therapy

Most women with osteoporosis — For most postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, we suggest oral bisphosphonates as first-line therapy (algorithm 2). We prefer oral bisphosphonates as initial therapy because of their efficacy, favorable cost, and the availability of long-term safety data.

Selection of oral bisphosphonate (usually preferred) — We typically prefer alendronate as our choice of oral bisphosphonate due to efficacy in reducing vertebral and hip fracture and evidence showing residual fracture benefit after a five-year course of therapy is completed 23. Risedronate is a reasonable alternative. Generic alendronate and risedronate are available in many countries, including the United States. Most patients prefer the convenience of the once-weekly regimen.

Contraindications and precautions — Oral bisphosphonates should not be used as initial therapy in patients with esophageal disorders (achalasia, scleroderma involving the esophagus, esophageal strictures), an inability to follow the dosing requirements (eg, stay upright for at least 30 to 60 minutes), or advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD; estimated glomerular filtration [eGFR] rate <30 mL/min/1.73 m2) (algorithm 2).

Oral bisphosphonates also should be avoided after certain types of bariatric surgery in which surgical anastomoses are present in the gastrointestinal tract (eg, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass).

All patients should have normal serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels prior to starting pharmacotherapy, and they should receive supplemental calcium and vitamin D if dietary intake is inadequate

Gastrointestinal malabsorption or difficulty with dosing requirements — For patients with esophageal disorders, gastrointestinal intolerance, history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or an inability to follow the dosing requirements of oral bisphosphonates, we suggest intravenous (IV) bisphosphonates.

- Zoledronic acid – For patients unable to take oral bisphosphonates, we prefer IV zoledronic acid, which reduces vertebral and hip fractures. IV ibandronate is also available; however, no direct fracture prevention data exist for IV ibandronate.

- Denosumab – Denosumab is an alternative to IV zoledronic acid for women at high risk for fracture who have difficulty with the dosing requirements of oral bisphosphonates or who prefer to avoid IV bisphosphonates due to side effects (eg, acute phase reaction). It may be used as initial therapy in certain patients at high risk for fracture, such as older patients who have difficulty with the dosing requirements of oral bisphosphonates.

Denosumab – Denosumab is an alternative to IV zoledronic acid for women at high risk for fracture who have difficulty with the dosing requirements of oral bisphosphonates or who prefer to avoid IV bisphosphonates due to side effects (eg, acute phase reaction). It may be used as initial therapy in certain patients at high risk for fracture, such as older patients who have difficulty with the dosing requirements of oral bisphosphonates.

In several trials in postmenopausal women, denosumab improved BMD and reduced the incidence of new vertebral, hip, and nonvertebral fractures. If denosumab is discontinued, administering an alternative therapy (typically a bisphosphonate) is advised to prevent rapid bone loss and vertebral fracture.

Contraindications or intolerance to any bisphosphonates — Patients who are allergic to bisphosphonates or who develop severe bone pain with them require an alternative treatment. For patients who cannot take oral or IV bisphosphonates, the choice of agent depends on risk of fracture (eg, history of prior fragility fractures, T-score, comorbidities), drug efficacy and adverse effect profile, and patient preferences.

Very high fracture risk — For patients with very high fracture risk (eg, T-score of ≤-2.5 plus a fragility fracture, T-score of ≤-3.0 in the absence of fragility fracture[s], history of severe or multiple fractures), we suggest initial treatment with an anabolic agent (teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab).

Patients most likely to benefit from anabolic therapy are those with the highest risk of fracture (eg, T-score ≤-3.5 with fragility fracture[s], T-score ≤-4.0, recent major osteoporotic fracture, or multiple recent fractures).

For patients with very high fracture risk who cannot be treated with an anabolic agent due to cost, inconvenience, contraindications, or personal preference, a bisphosphonate or denosumab may be appropriate (algorithm 2). Patients should be under the care of a provider with expertise in treating osteoporosis to facilitate shared decision-making.

Fig. 2 Algorithm for choice of biphosphate

In contrast to antiresorptive agents, the anabolic agents teriparatide and abaloparatide stimulate bone formation and activate bone remodeling.

The anabolic agent romosozumab uniquely stimulates bone formation and inhibits bone resorption. In postmenopausal women with very high fracture risk, trial data demonstrate greater fracture prevention with anabolic therapies compared with oral bisphosphonates 24,25.

For postmenopausal women with very high fracture risk (eg, T-score of ≤-2.5 plus a fragility fracture, T-score of ≤-3.0 in the absence of fragility fracture(s), history of severe or multiple fractures) who were not treated initially with anabolic therapy, we suggest switching to an anabolic agent (teriparatide, abaloparatide, romosozumab).

Denosumab is an alternative.

After initial therapy with an anabolic agent is discontinued, patients should be treated with an antiresorptive agent (typically a bisphosphonate) to preserve the gains in BMD from anabolic therapy. For individuals who are unable to tolerate oral or intravenous bisphosphonates, alternatives may include denosumab or raloxifene.

For women without very high fracture risk, treatment options include the following :

- Denosumab – Denosumab is not considered initial therapy for most patients with osteoporosis but is an option for patients who are intolerant of or unresponsive to any bisphosphonate, those with impaired kidney function, or those in whom desired increases in BMD exceed typical gains achieved with oral bisphosphonate therapy.

- Raloxifene – We reserve the use of the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) raloxifene for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis and without history of fragility fractures who are not candidates for any bisphosphonate or denosumab. Raloxifene is also a reasonable choice in women with increased risk of invasive breast cancer. Among SERMs, we prefer raloxifene because it has eight-year safety and efficacy data and also reduces the risk of breast cancer. Raloxifene inhibits bone resorption and reduces the risk of vertebral fracture. However, the antiresorptive effects of SERMs are less potent than those of bisphosphonates. Raloxifene increases thromboembolic events and possibly hot flashes and has no apparent effect on heart disease or the endometrium.Tamoxifen is another SERM used primarily for the prevention and management of breast cancer. In postmenopausal women, tamoxifen therapy used to prevent or treat breast cancer likely confers protective effects on bone.Bazedoxifene, another SERM, is available in Europe and Japan for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Although it has similar efficacy as raloxifene in preventing and treating postmenopausal osteoporosis, bazedoxifene has few long-term safety data, and it has not been adequately studied for breast cancer prevention. It is not available as a standalone drug in the United States

- Estrogen/progestogen therapy — Combined therapy with an estrogen and progestogen (either natural or synthetic [ie, progestin]) is not a first-line approach for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women due to potential risks of therapy 26.

In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, estrogen-progestogen therapy (or estrogen-only therapy for those with prior hysterectomy) may be used if also indicated to treat persistent menopausal symptoms. Menopausal hormone therapy is also an option for women who are unable to tolerate any other antiresorptive therapy. In the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), both combined estrogen-progestin and estrogen-only treatment reduced hip and vertebral fracture risk.

- Anabolic therapy – While use of anabolic agents is generally reserved for individuals with very high risk of fracture, these agents may be used in patients with less severe osteoporosis (eg, T-score ≤-2.5 without a fragility fracture) who are unable to tolerate oral or IV bisphosphonates.

After initial therapy with an anabolic agent is discontinued, patients should be treated with an antiresorptive agent (typically a bisphosphonate) to preserve the gains in BMD from anabolic therapy. For individuals who are unable to tolerate oral or intravenous bisphosphonates, alternatives may include denosumab or raloxifene.

Selection of anabolic agent — Anabolic agents are not considered initial therapy for most patients. Possible candidates for anabolic agents include postmenopausal women with any of the following :

- Very high risk of fracture.

- Prior fragility fracture and contraindications or intolerance to any bisphosphonates.

- Fragility fracture and/or decline in BMD on other osteoporosis agent(s) despite treatment adherence.

If the decision is made to treat with an anabolic agent, options include teriparatide, abaloparatide, or romosozumab 27. Teriparatide has a long track record of safety, whereas fewer data exist for long-term use of abaloparatide.

Romosozumab induces a greater BMD response than either abaloparatide or teriparatide, but clinical experience is limited and long-term side effects are uncertain. Teriparatide and abaloparatide are administered as a daily subcutaneous injection. Romosozumab is administered by a health care professional once monthly as two subcutaneous injections.

Treatment with teriparatide/abaloparatide is generally limited to 18 to 24 months and with romosozumab to 12 monthly doses. However, treatment with teriparatide (brand name only) may be continued past 24 months in selected individuals if fracture risk remains high.

After initial therapy with an anabolic agent is discontinued, patients should be treated with an antiresorptive agent (preferably a bisphosphonate) to preserve the gains in BMD from anabolic therapy. For women who are unable to tolerate oral or IV bisphosphonates, denosumab or raloxifene are alternatives. Increased risk of vertebral fracture develops soon after discontinuation of denosumab, so the need for indefinite administration should be discussed with patients prior to its initiation.

Therapies not recommended — Numerous therapies have been evaluated for the treatment of osteoporosis with disappointing or conflicting results. We typically do not recommend the following therapies :

Combination therapy — We suggest not using combination therapy. Combination therapy has not been shown to provide additional benefit for fracture prevention compared with monotherapy. Combination osteoporosis therapies are discussed separately.

Calcitonin — We prefer other drugs to calcitonin because of its relatively weak effect on BMD and poor antifracture efficacy compared with bisphosphonates and parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein analogs 28. Concern exists about the long-term use of calcitonin for osteoporosis due its association with an increase in cancer rates.

Other — In postmenopausal women with osteoporosis or low BMD with high fracture risk, we do not routinely use any of the pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic therapies below.

Pharmacologic therapies

- Calcitriol

- Strontium

- Androgens

Supplemental therapies and vibration platforms

- Vitamin K

- Folate/vitamin B12

- Fluoride

- Vibration

References

- LeBoff MS, Greenspan SL, Insogna KL, Lewiecki EM, Saag KG, Singer AJ, Siris ES; 2022. The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int.;33(10):2049. Epub 2022 Apr 28.

- McClung M, Clemmesen B, Daifotis A, Gilchrist NL, Eisman J, Weinstein RS, Fuleihan G el-H, Reda C, Yates AJ, Ravn P (1998) Alendronate prevents postmenopausal bone loss in women without osteoporosis. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Alendronate Osteoporosis Prevention Study Group. Ann Intern Med.;128(4):253.

- Ravn P, Weiss SR, Rodriguez-Portales JA, McClung MR, Wasnich RD, Gilchrist NL, Sambrook P, Fogelman I, Krupa D, Yates AJ, Daifotis A, Fuleihan GE; (2000) Alendronate in early postmenopausal women: effects on bone mass during long-term treatment and after withdrawal. Alendronate Osteoporosis Prevention Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.;85(4):1492.

- Hosking D, Chilvers CE, Christiansen C, Ravn P, Wasnich R, Ross P, McClung M, Balske A, Thompson D, Daley M, Yates AJ; (1998) Prevention of bone loss with alendronate in postmenopausal women under 60 years of age. Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort Study Group. N Engl J Med;338(8):485.

- McClung MR, Wasnich RD, Hosking DJ, Christiansen C, Ravn P, Wu M, Mantz AM, Yates J, Ross PD, Santora AC 2nd (2004) Prevention of postmenopausal bone loss: six-year results from the Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort Study. Early Postmenopausal Intervention Cohort Study; J Clin Endocrinol Metab ;89(10):4879.

- Ravn P, Bidstrup M, Wasnich RD, Davis JW, McClung MR, Balske A, Coupland C, Sahota O, Kaur A, Daley M, Cizza G; (1999) Alendronate and estrogen-progestin in the long-term prevention of bone loss: four-year results from the early postmenopausal intervention cohort study. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med;131(12):935.

- Cranney A, Tugwell P, Adachi J, Weaver B, Zytaruk N, Papaioannou A, Robinson V, Shea B, Wells G, Guyatt G (2002) Meta-analyses of therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. III. Meta-analysis of risedronate for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Methodology Group and The Osteoporosis Research Advisory Group; Endocr Rev;23(4):517.

- Mortensen L, Charles P, Bekker PJ, Digennaro J, Johnston CC Jr; (1998) Risedronate increases bone mass in an early postmenopausal population: two years of treatment plus one year of follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.;83(2):396.

- Fogelman I, Ribot C, Smith R, Ethgen D, Sod E, Reginster JY; (2000) vRisedronate reverses bone loss in postmenopausal women with low bone mass: results from a multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMD-MN Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab;85(5):1895.

- McClung MR, Wasnich RD, Recker R, Cauley JA, Chesnut CH 3rd, Ensrud KE, Burdeska A, Mills T, (2004) Oral daily ibandronate prevents bone loss in early postmenopausal women without osteoporosis.Oral Ibandronate Study Group; J Bone Miner Res;19(1):11.

- Biennial (2009) IV zoledronic acid (Reclast) for prevention of osteoporosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther.;51(1315):49.

- http://www.fda.gov/drugs/newsevents/ucm370679.htm (Accessed on October 10, 2013).

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, Aragaki AK, Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Anderson G, Howard BV, Thomson CA, LaCroix AZ, Wactawski-Wende J, Jackson RD, Limacher M, Margolis KL, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Beresford SA, Cauley JA, Eaton CB, Gass M, Hsia J, Johnson KC, Kooperberg C, Kuller LH, Lewis CE, Liu S, Martin LW, Ockene JK, O’Sullivan MJ, Powell LH, Simon MS, Van Horn L, Vitolins MZ, Wallace RB; JAMA. (2013) Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. Oct;310(13):1353-68.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J, (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators; JAMA;288(3):321.

- Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, Bonds D, Brunner R, Brzyski R, Caan B, Chlebowski R, Curb D, Gass M, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix S, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell A, Jackson R, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller L, LaCroix AZ, Lane D, Langer RD, Lasser N, Lewis CE, Manson J, Margolis K, Ockene J, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Ritenbaugh C, Robbins J, Rossouw JE, Sarto G, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Wallace R, Wassertheil-Smoller S, (2004) Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Women’s Health Initiative Steering Committee; JAMA.;291(14):1701.

- Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, Cummings SR, Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, LeBoff M, Lewis CE, McGowan J, Neuner J, Pettinger M, Stefanick ML, Wactawski-Wende J, Watts NB, (2003) Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. Women’s Health Initiative Investigators; JAMA.;290(13):1729.

- Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kleerekoper M, Pickar JH; (2002) Effect of lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens with and without medroxyprogesterone acetate on bone in early postmenopausal women. JAMA;287(20):2668.

- Prestwood KM, Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Kulldorff M; (2003) Ultralow-dose micronized 17beta-estradiol and bone density and bone metabolism in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA.;290(8):1042.

- Ettinger B, Ensrud KE, Wallace R, Johnson KC, Cummings SR, Yankov V, Vittinghoff E, Grady D; (2004) Effects of ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol on bone mineral density: a randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol;104(3):443.

- LeBoff MS, Greenspan SL, Insogna KL, Lewiecki EM, Saag KG, Singer AJ, Siris ES; (2022) The clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis Osteoporos Int;33(10):2049. Epub 2022 Apr 28.

- Conley RB, Adib G, Adler RA,Åkesson KE, Alexander IM, Amenta KC, Blank RD, Brox WT, Carmody EE, Chapman-Novakofski K, Clarke BL, Cody KM, Cooper C, Crandall CJ, Dirschl DR, Eagen TJ, Elderkin AL, Fujita M, Greenspan SL, Halbout P, Hochberg MC, Javaid M, Jeray KJ, Kearns AE, King T, Koinis TF, Koontz JS, Kužma M, Lindsey C, Lorentzon M, Lyritis GP, Michaud LB, Miciano A, Morin SN, Mujahid N, Napoli N, Olenginski TP, Puzas JE, Rizou S, Rosen CJ, Saag K, Thompson E, Tosi LL, Tracer H, Khosla S, Kiel DP; J Bone Miner Res. (2020) Secondary Fracture Prevention: Consensus Clinical Recommendations from a Multistakeholder Coalition. ;35(1):36. Epub 2019 Dec 1.

- Wong RMY, Wong PY, Liu C, Wong HW, Chung YL, Chow SKH, Law SW, Cheung WH; (2022) The imminent risk of a fracture-existing worldwide data: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int.;33(12):2453. Epub 2022 Jul 1.

- Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, Cauley JA, Levis S, Quandt SA, Satterfield S, Wallace RB, Bauer DC, Palermo L, Wehren LE, Lombardi A, Santora AC, Cummings SR, (2006) Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. FLEX Research Group; JAMA;296(24):2927.

- Kendler DL, Marin F, Zerbini CAF, Russo LA, Greenspan SL, Zikan V, Bagur A, Malouf-Sierra J, Lakatos P, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Lespessailles E, Minisola S, Body JJ, Geusens P, Möricke R, López-Romero P; (2018) Effects of teriparatide and risedronate on new fractures in post-menopausal women with severe osteoporosis (VERO): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet;391(10117):230. Epub 2017 Nov 9.

- Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, Karaplis AC, Lorentzon M, Thomas T, Maddox J, Fan M, Meisner PD, Grauer A; (2017) Romosozumab or Alendronate for Fracture Prevention in Women with Osteoporosis. N Engl J Med.;377(15):1417. Epub 2017 Sep 11.

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J, (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators; JAMA.288(3):321

- Shoback D, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Eastell R; (2020) Pharmacological Management of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society Guideline Update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab;105(3)

- Downs RW Jr, Bell NH, Ettinger MP, Walsh BW, Favus MJ, Mako B, Wang L, Smith ME, Gormley GJ, Melton ME; (2000) Comparison of alendronate and intranasal calcitonin for treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab;85(5):1783.

Author Information

Nandar Min Swe, MD

Endocrinologist

Optum Medical Group, CA, USA