Schistosomiasis (Bilharzia, snail fever )

1. Clinical features: An adult blood fluke (trematode) infection with adult worms living within the mesentery vein or the venous plexus of the bladder of the host over a life span of many years. Mated female worms release eggs into the circulation and depending on the species (Schistosoma mansoni Schistosoma japonican or Schistosoma haematobium), eggs make their way to the bowel or the bladder and shed the eggs in phases. Eggsthat fail to pass out of the body develop into granulomata or fibrosis in the organ they lodge.

Symptoms are related to the host immune response to the schistosoma eggs and may vary due to the number and location of the eggs. Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonican primarily give rise to hepatic or intestinal pathology.Signs andsymptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain and hepatosplenomegaly. Long duration and high intensity of infection leads to liver fibrosis and portal hypertension and Schistosoma haematobium gives rise to urinary manifestations. Signs and symptoms include dysuria, urinary frequency and haematuria at the end of urination.Chronic infection can cause hydronephrosis, changes in the female genital tract and associated with increased risk of bladder cancer in both sexes. Neuroschistosomiasis, the lodging of eggs in the spinal cord, is rare but can develop. Eggs lodging in the brain are more common with eggs Schistosoma japonicum .Larvae of schistosomes of birds and mammals can penetrate human skin and cause dermatitis sometimes known as swimmers itch: those schistosomes do not mature in humans.

Acute infection can cause systematic manifestation such as Katamaya fever) which has been reported in travellers to endemic areas. Signs and symptoms of acute schistomiasis include: fever, headache, rash myalgia, diarrhea and respiratory symptoms.

Genital manifestations of schistosomiasis

Human schistosomiasis (bilharzia) is a parasitic disease prevalent in tropical areas. Although the clinical manifestations in the urinary1 or gastrointestinal2 tracts are widely known, many clinical health-care professionals are unaware of the genital manifestations which are often ignored or underestimated. Schistosoma haematobium is the main species causing genital manifestations but other species of schistosomiasis have been implicated. The number of people suffering from genital manifestations is not precisely known. The biological plausibility of a causal association between genital schistosomiasis and HIV has been described, and may be an important factor in increasing the risk of contracting HIV in areas or communities where both infections are co-endemic.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical manifestations of genital schistosomiasis occur both in women and in men.

In men, the symptoms include epididymitis (an inflammation of the epididymis at the back of the testicle) which can simulate tuberculosis and associated funiculitis, indolence and possible fistulization, hemospermia, pain during urination and prostatitis.

In women, the symptomatology is unspecific because urogenital schistosomiasis can provoke gynaecological ailments. The most frequently observed signs and symptoms are abdominal and pelvic pain presenting in forms such as dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, leucorrhoea, menstrual disorders, post-coital bleeding or simple contact bleeding (during an examination), cervicitis, Endometritis and salpingitis. The disease evolves into a chronic condition. These genital lesions can cause complications such as early abortion, ectopic pregnancy and infertility. The clinical appearance of genital lesions is variable. Traditionally, the only specific lesions in women were considered to be granulomatous lesions the size of a pinhead and visible to the naked eye that looks like sand grains. They are rough to the touch and have a sandy consistency (“sandy patches”). Several field studies and researchers have described other lesions such as papilloma, polyps and neovascularization.

Diagnosis

Genital schistosomiasis may be associated with the presence of schistosome eggs (ova) in the genitals in both men and women. However, ova are not always concurrently present, and current laboratory methods have a low sensitivity to confirm their presence. Lesions associated with genital schistosomiasis may mimic a host of infections and premalignant or malignant conditions. It is therefore crucial to identify alterations that are pathognomic. Differential diagnosis must be done systematically to screen for cancers (of the vulva, vagina, cervix, and endometrium), sexually transmitted infections and urogenital tuberculosis.

Clinical diagnosis of female genital schistosomiasis is mainly done by visual inspection and histological methods.

2. Causative agents: S.mansoni S.haematobium and S.japonican are the major species causing human disease. S. mekongi and intercalatum are only important in limited areas

3. Diagnosis: I made through presence of eggs in the stools by direct smear or using Kato Kart technique. S. haematobium and S. japonicum by examination of urine precipitate (Neuclepore filtration). Serologic testing is useful for the diagnosis of the travellers infections but current available methods do not distinguish between and current infections. Useful immunologic test includes the immunoblot test, the circumoval precipitin, immunofluorescene assay, enzyme linked immunosorbant assay with egg or adult antigen positive results of serological antibody detection test could be indicative of prior infection and are not the proof of current infection

4. Occurrence: S. mansoni is found in Africa, Arabian Peninsula, Brazil, Suriname and Venezuela in South America and Caribbean islands, S.haematobium is found in Africa and Middle East.

S.japonicum is found in China,Philippines and Sulawesi of Indonesia. S.mekongi was found in Mekong River basin of Cambodia and Laos People Republic. S.intercalanus was found in parts of central and western Africa.

5. Human are the principle reservoir of S. mansoni, S.intercalanus and S.haematobium. Human cats, dogs, pigs, cattle and water buffalo and wild rodents are potential reservoirs of S.japonicum; there relative epidemiological importance varies from different regions. Epidemiological persistence of the parasites depends on the presence of the appropriate snail, intermediate host (species of the genus Blomphalaria for S.mansoni, Bulinus for S.haematobium and S.intercalatum, Oncomelania for S.japonicum and Tricula for S.mekongi)

6. Incubation period: The incubation period for patients with acute schistosomiasis is usually 14-84 days; however, many people are asymptomatic and have subclinical disease during both acute and chronic stages of infection. Persons with acute systemic manifestations (Katayama fever) may occur in primary infections 2-6 weeks after exposure immediately preceding and during initial egg deposition.

7. Transmission: Infections occur when cercariaeor free living larval form penetrate the skin. In the human host cercariae become schistosomula migrate through various tissue before developing into adults worms Adult worms of S.maspni, S.japonicum, S.mekongi and S.intercalatum remain in the mesenteric vein those of S.haematobium migrate to the venous plexus of urinary bladder. Eggs are deposited and escaped into the lumen of bowel or urinary bladder or end up lodging in other organs including the liver and the lungs. The eggs of S.haematobium leave the body mainly in the urine. In other species, eggs leave through the faeces and hatch and liberated larvae (miracidia) penetrate into suitable freshwater snail intermediate host. After several weeks of amplification through asexual reproduction, cercariae emerge from the snail: infected snails continue release cercariae as long as they live.

Schistosomiasis is not communicable directly from person to person. Infected persons who are shedding eggs maintain in areas with appropriate snail host and poor sanitation. S.mansoni and S.haematobium worms can survive for more than 10 years in an infected human.

8. Risk group: Susceptibility is universal. Risk is higher in groups with greatest exposure to water containing cercariae. Any immunity developing as a result of infection is variable and not yet fully understood.

9. Prevention:

- In endemic areas, regular mass drug treatment with praziquantel is recommended for: population at risk including school age children, woman of child bearing age and certain groups who have occupational water exposure.

- The disposal of feces and urine is important so that viable eggs will not reach bodies of fresh water containing intermediate snail host. The control of animals infected with S.japonicum is desirable but difficult.

- Improve irrigation and agriculture practices to reduce snail habitat by reducing, draining and filling marshy areas or lining canals with concrete.

- Where appropriate, treat snail breeding sites with molluscicides. The cost and environmental impact will limit the utility of these agents.

- Minimize the exposure to contaminated water (e.g by wearing rubber boots). The application of topical water resistant preparations containing N-N-diethyl-meta-torluamidemay can prevent cercarial penetration but total coverage is difficult. Immediate vigorous towel drying has been suggested to reduce cercarial penetration after accidental water contact for all but the briefest of exposure.

- Provide water for drinking, bathing and washing clothes from sources free from cercaria or treated to kill them. Effective measures for inactivating cercariae include water treatment with iodine or chlorine although these agents may not activate other pathogens present in contaminated water. Allowing water to stand 18 – 72 hours before use is effective.

- Travellers visiting the endemic areas should be advised of the risks and informed about preventive measures. Local tourist information suggesting fresh water bodies are free from schistosomiasis not always reliable.

10. Management of cases

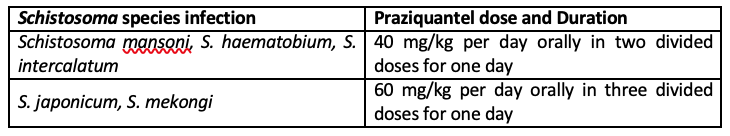

Infections with all major Schistosoma species can be treated with praziquantel. The timing of treatment is important since praziquantel is most effective against the adult wormand requires the presence of a mature antibody response to the parasite. For travelers, treatment should be at least 6-8 weeks after last exposure to potentially contaminate freshwater. One study has suggested an effect of praziquantel on schistosome eggs lodged in tissues. Limited evidence of parasite resistance to praziquantel has been reported based on low cure rates in recently exposed or heavily infected populations; however, widespread clinical resistance has not occurred. Thus, praziquantel remains the drug of choice for treatment of schistosomiasis. Host immune response differences may impact individual response to treatment with praziquantel. Although a single course of treatment is usually curative, the immune response in lightly infected patients may be less robust, and repeat treatment may be needed after 2 to 4 weeks to increase effectiveness. If the pre-treatment stool or urine examination was positive for schistosome eggs, follow up examination at 1 to 2 months post-treatment is suggested to help confirm successful cure.

11. Management of contacts and the immediate environment

Investigate contacts for infection from common source

12. Special considerations

(1) Reporting requirement

(2) Surveillance case definition for endemic areas: screening for the urinary schistosomiasis is based on the detection of visible hematuria, positive reagent strip or S.haematobium egg in the urine screening for the intestinal schistosomiasis is based on the detection of eggs in the stool.

(3) Epidemic measures: examine for schistosomiasis and treat all who are infected, especially with those with disease and/or moderate or heavy intensity of infection: pay particular attention to children. Provide clean water and warn people against contact with water, possibly contain incercariae and prohibit contamination of water by urine and feces. Treat areas containing high snail densities with molluscicides as appropriate

Country situation

Recent outbreak of schistosomiasis was reported by pediatrician Dr. San Mu of Sittwe General Hospital of Rakhine State that out of (574)suspected cases, 302 cases were positive for IgM of Schistosoma mansoni by ELISA examination.

Abstract of Research Study: Htin Zaw Soe1, Cho Cho Oo2, Tin Ohn Myat3 and Nay Soe Maung4

Detection of Schistosoma Antibodies and exploration of associated factors among local residents around Inlay Lake, Southern Shan State, Myanmar

Abstract

Background: Schistosomiasis is a chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes (trematode worms) of the genus Schistosoma. Its transmission has been reported in 78 countries affecting at least 258 million people world-wide. It was documented that S. japonicum species was prevalent in Shan State, Myanmar, but the serological study was not conducted yet. General objective of the present study was to detect schistosoma antibodies and explore associated factors among local residents living around Inlay Lake, NyaungShwe Township, and Southern Shan State, Myanmar.

Methods: An exploratory and cross-sectional analytic study was conducted among local residents (n = 315) in selected rural health center (RHC) areas from December 2012 through June 2013. The participants were interviewed with pretested semi-structured questionnaires and their blood samples (serum) were tested using Schistosomiasis Serology Microwell ELISA test kits (sensitivity 100% and specificity 85%) which detected IgG antibodies but could not distinguish between a new and past infection. Data collected were analysed by SPSS software 16.0 and associations of variables were determined by Chi-squared test with a significant level set at 0.05.

Results: Schistosomasero prevalence (IgG) in study area was found to be 23.8% (95% CI: 18.8–28.8%). The present study is the first and foremost study producing serological evidence of schistosoma infection—one of theneglected tropical diseases—in local people of Myanmar. The factors significantly associated with seropositivitywere being male [OR = 2.6 (95% CI: 1.5–4.49), P < 0.001], residence [OR = 3.41 (95% CI: 1.6-7.3), P < 0.05 for KhaungDaing vs. Min Chaung] and education levels [OR = 4.5 (95% CI: 1.18–17.16), P< 0.05 for illiterate/3Rs level vs. high/graduate and OR = 3.16 (95% CI: 1.26 – 7.93), P< 0.05 for primary/middle level vs. high/graduate] all factors classically associated with risk of schistosomainfection. None of the behavioural factors tested were significantly associated with seropositivity.

Conclusion: Schistosoma infection serologically detected was most probably present at some time in this locationof Myanmar, and this should be further confirmed parasitologically and kept under surveillance. Proper trainings ondiagnosis, treatment, prevention and control of schistosomiasis should be provided to the healthcare providers.

Keywords: Schistosomiasis, Associated factors, Inlay Lake, Myanmar, Seroprevalence, Elisa

Schistosomiasis: Myanmar Country situations and actions

Schistosomiasis is an acute and chronic parasitic disease caused by blood flukes (worms). The disease has been reported from 78 countries in the world. People become infected when larval forms of parasites penetrate the skin of human after being released by freshwater snails. Human to human transmission is not possible. Recently, schistosomiasis is reported also from Myanmar, viz. Rakhine State, Southern Shan State (near Lake Inle) and Bago Region. Between October 2016 and 30 November 2018, a total of 1,734 suspected cases tested and 947 were found serologically positive (IgG positive).

To support the prevention and control efforts by the national health authorities, WHO provided technical guidelines, partook in field investigation and mobilized essential commodities for diagnosis and treatment. An expert mission comprised of expert from WHO and MOHS fielded in Myanmar to assess the situation and to advice on the future course of action. The expert mission visited some parts of Rakhine region and concluded the feasibility of transmission. The mission recommended to provide efforts to confirm diagnosis of schistosomiasis by confirmatory tests as well as intermediate host – the snail. The mission also recommended to map the disease prevalence and prevalence of snails in the country as per WHO standard Operating Procedure (SOPs).

The control of schistosomiasis is based on large-scale treatment of at-risk population groups (depending on the endemicity of the disease), access to safe water, improved sanitation, hygiene education, and snail control.