Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is now recognised as one of the most common chronic respiratory and sleep disorders. It is a conditioncharacterized by repetitive episodes of complete or partial obstruction of the upper airway during sleep.

Epidemiology

Most epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that OSA is two to three times more prevalent among men than women1 and the prevalence of OSA increases with age through midlife. The prevalence of OSA varies somewhat based on ethnicity, recruitment methods, technology used to record airflow, definitions of apnea and hypopneaand cut-off point of AHI2.

Pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea

The pathogenesis of OSA involves a complex interaction of factor including: altered upper airway anatomy, tissue characteristics and neuromuscular function, sleep-related decrements in upper airway dilator muscle activity, attenuated protective dilator reflexes, altered ventilator, arousal responses to chemical and other respiratory stimuli. Different factors may predominate in different individuals, yielding different OSA phenotypes. The upper airway in OSA closes only during sleep, indicating that sleep-dependent changes in output to the dilator muscles of the upper airway are clearly a fundamental mechanism. Airway collapse ensues when dilator muscle activity and compensatory reflexes are no longer sufficient to maintain patency of the compromised airway2.

Clinical factors predisposing to obstructive sleep apnea

Factors that predispose to OSA are obesity, upper airway anatomic abnormalities, body position, genetic factors, endocrine disturbances, smoking, alcohol and drugs2.

Clinical features of obstructive sleep apnea

The patient complaints include daytime sleepiness, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, or insomnia. The patient may also waken with breath-holding, gasping, or choking and symptoms may present for years without being noticed by patients. The bed partner reports loud snoring, breathing interruptions or both during the patient’s sleep2.

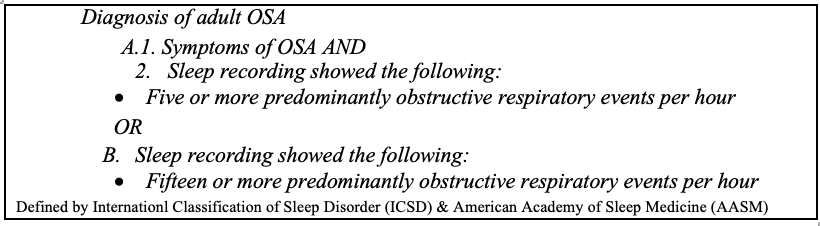

Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea

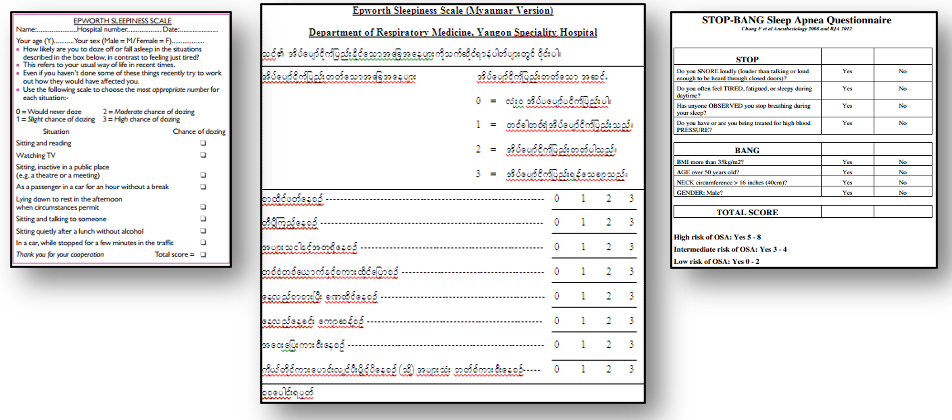

Several questionnaires such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), STOP-BANG or Berlin questionnaires are used for subjective assessment of patients. However, the gold standard for the diagnosis of OSA is full overnight polysomnography (PSG), performed in an attended sleep laboratory setting1.

According to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine manual vesion 2.33, apnea and hypopnea are defined as follows. Apnea is defined as an event lasting ≥10 secondcharacterized by ≥90% reduction from pre-event baseline in oronasal thermistor airflow.Hypopnea is defined as an event lasting ≥10 sec characterized by a ≥30% reduction from pre-event baseline in peak nasal pressure inspiratory airflow that is associated with either of the following: either a ≥3% reduction in oxygen saturation (SpO2) pre-event baseline or a microarousal. Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) is calculated as numbers of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep.

Consequences of untreated obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiac and cerebrovascular events. The meta-analysis indicates that moderate and severe OSA are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes 4. OSA is also shown to be associated with insulin resistance independent of obesity and has negative impact on glycemic control 5.

OSA increases 24-hour mean blood pressure and the increase is greater in those with recurrent nocturnal hypoxemia5. All types of cardiac arrhythmia are reported in patients with OSA and its prevalence is increased with increased severity of hypoxemia 6. OSA is also found to be prevalent in patients with coronary artery disease7 and cerebrovascular disease 8.

Patients with OSA are reported to be at increased risk perioperatively because of difficulty in intubation and upper airway obstruction during the recovery period5. Untreated OSA is associated with increased mortality and it is related to cardiovascular deaths that occur largely in individuals with severe OSA with or without sleepiness 1.

Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea

Generally, treatment options for OSA are continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral appliances such as mandibular advancement device and surgery. Behavioral strategies such as weight reduction, physical exercise, avoidance of sedatives and alcohol are important treatment options for sucessful outcomes.

CPAP delivers a preset level of pressurized air to the upper airway that prevents airway closure by acting as a “pneumatic splint” and is administered at a constant level throughout both inspiration and expiration 1. Mandibular advancement devices (MADs) are recommended for patients with mild to moderate OSA or for those unable or unwilling to use CPAP. Tongue-retaining devices are less effective 2.Positional therapy is suggested in purely positional apnea. Hypoglossal nerve stimulation devices are currently being evaluated for effectiveness in OSA2.

More invasive surgical procedures such as maxillomandibular advancement or multilevel surgery are recommended only after other alternative treatments have failed. The most commonly applied techniques are surgical reduction of palatal region (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty), laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty and radiofrequency-based procedures. Tracheostomy is recommended only when all other options have been exhausted2.

Current situation of OSA and health care facilities for OSA patients in Myanmar

OSA is not an uncommon disorder in Myanmar 1 although the epidemiological data is not available at this time. In the past five year hospital-based analytical9 and descriptive10 studies done in the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Yangon Specialty Hospital the prevalence of suspected OSA patients seeking medical advice was approximately 5% of total admissions. More than 90% of these patients were found to have sleep disorder breathing, mainly of obstructive sleep apnea with varying disease severity. This data regarding OSA reflects only the tip of the iceberg of the disorder among the general population.

Awareness of OSA is expected to increase in future.We now have a better understanding of the consequences of sleep disorder breathing, particularly its significant adverse effects on cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and metabolic diseases and have seen the positive effects of treatment in OSA patients. When OSA patients receive proper treatment, they not only normalize the disease indicator but also have remarkable improvement on health related quality of life (HRQoL); functional activities, vigilance, sexual activity, general productivity and social outcome. Therefore, the recognition of the sleep disorder breathing and providing better guidance to get the correct diagnosis and treatment in OSA patients is of great importance for primary care providers.

As mentioned earlier, although OSA is not uncommon in our country but has been under diagnosed until recently. OSA can be screened and triaged according to their symptomatology and questionnaires using two well-known screening questionnaires such as Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) for assessing sleepiness and the STOP-BANG questionnaire to screen the likelihood of OSA. When combined with the risk factors of OSA, effected individuals can readily be diagnosed and referred for further evaluation at the specialist center.

We are now well equipped with efficient sleep medicine facilitiesto diagnose and treat our patients in own country. These patients are initailly seen byspecailistsat theoutpatient setting focusing on comprehensive sleep history and evaluation and sleep studysubsequently performed in a sleep laboratory.The gold standarddiagnostic test for sleep disorder, technically termed as fully attended overnight (level 1) in-laboratory polysmnographyand limited sleep study (level 3) polygraphy, recording respiratory and oxygenation without neurology parameters,are being carried out to diagnose sleep disorders in theDepartments of Respiratory Medicine, both in Upper and Lower Myanmar.

The patients confirmedto have OSA are then allowed to get proper treatment depending upon disease severity, patient’s perference and socioeconomic background. The most widely used and preferred treatment option by our OSA patients is found to be CPAP therapy. The patients on CPAP treatment are also offered follow up care by specialists in Respiratory Medicine outpatient clinics for better compliance and successful treatment outcome.

Our standard of carefor OSA patients has been fruitful with expertise and institutional facilities which are in line with international sleep centers.

References

- Pien, G. and Pack, I. (2010) Disorders in the control of breathing. In: Mason, R., Broaddus, C., Martin, T., Schraufnagel, D., Murray, J., Nadel, J. and King, T. Sleep Disordered Breathing. 5th edition. Philadelphia. Saunders. pp. 1881-1900.

- Kimoff, R. (2016) Disorders of Sleep and Control of Breathing. In: Mason, R., Broaddus, C., Martin, T., Ernst, J., King, T., Lazarus, S., Murray, J., Nadel, J., Slutsky, A. and Gotway, M. (eds) Obstructive Sleep Apnea. 6th edition. Philadelphia. Saunders. pp.1552-1568.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events version 2.3. (2016) Darien, U.S.A, 1-123.

- Wang, X., Bi Y., Zhang, Q. & Pan, F. (2013) Obstructive sleep apnoea and the riskof type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies.Respirology.18, 140–146.

- Douglas, N. (2008) Diseases of the Respiratory System. In: Fauci, A., Brawunwald, E., Kasper, D., Hauser, S., longo, D., Jameson, J. and Loscalzo, J. (eds) Sleep Apnea. 17th edition, U.S.A. McGraw-Hill. pp.1547.

- Hersi, A. S. (2010) Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiac arrhythmias. Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 5(1),11-17.

- Peker, Y., Kraiczi, H., Hedner, J., Loth, S., Johansson, A. & Bende, M. (1999) An independent association between obstructive sleep apnoea and coronary artery disease. EurRespir J. 14, 179 –184.

- Johnson, K. G. & Johnson, D. C. (2010) Frequency of sleep apnea in stroke and TIA patients: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 6(2), 131–137.

- Win WinMyint (2017)The outcome of nasal stent versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Dr.Med.Thesis, University of Medicine (1) Yangon, 1, 54.

- Khaing-Pwint-Wai (2015) Study of metabolic syndrome in patients with obstructive sleep apnea in Yangon General Hospital and Yangon Specialty Hospital. M.Med.Sc. (Internal Medicine)Dissertation, University of Medicine (1), Yangon, 21-22, 27.