Over-view Of Haemorrhoidal Disease and Options of Treatment

Introduction

Haemorrhoids are the fibrovascular anal cushions situated inside the anal canal, playing an important role in the closure mechanism of the canal ring.

Haemorrhoidal disease arises from the haemorrhoids, which are the normal components of the anorectal anatomy.

We have known haemorrhoidal disease since ancient times. It has been mentioned in texts of ancient Greeks and Egyptians. It is one of the commonest diseases that surgeons treat in daily surgical practice. Therefore, a large number of options have been developed for the treatment of haemorrhoidal disease, each of them having certain indications and applications.

Hospital-based proctoscopy studies reported the presence of haemorrhoids in up to 86% of patients, even though many of them were asymptomatic1.

The need for treatment is influenced by the severity of symptoms.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

Haemorrhoidal tissue is a normal component of the human anorectal anatomy contributing to anal continence and preventing damage to the sphincter mechanism during defaecation. Normally, when there is an increase in abdominal pressure (eg. sneezing, coughing or straining) the anal cushions engorge and maintain closure of the anal canal to prevent leakage of faeces and flatus. At the time of a bowel movement, the fibrovascular anal cushions protect the anal canal and allow it to dilate without tearing2,3.

Haemorrhoidal disease is seen only in adults and almost never in young children and adolescents. The main reason for this is the normally functioning haemorrhoids in young age, protecting haemorrhoidal disease. Haemorrhoidal disease usually appear only when pathological changes of the haemorrhoidal tissue take place (degenerative changes due to aging).

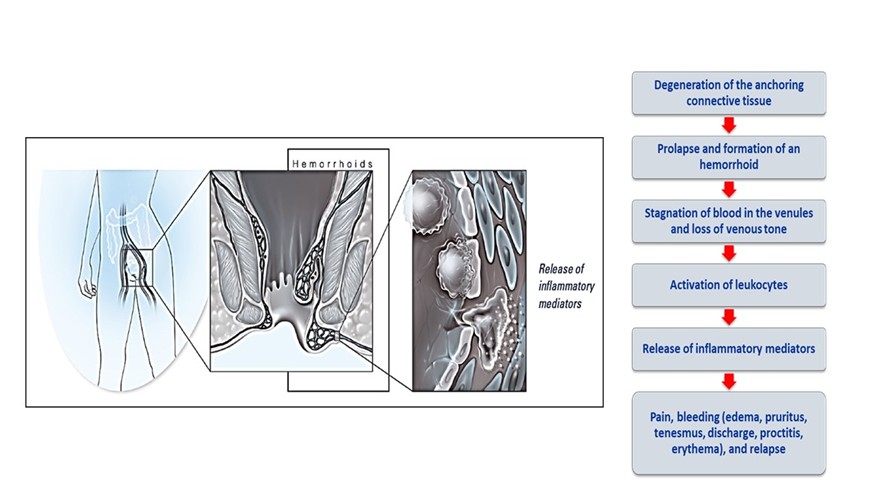

The degenerative changes (Figure 2) of supporting tissue of the haemorrhoids (Treitz muscle and Park’s ligaments) usually start during the third decade of life. This leads to the relaxation of the supporting mechanism of the haemorrhoids, which makes them more mobile, whenever intrarectal pressure increases. Due to that increase, the suspensory ligament and the ligament of Parks rupture, resulting in prolapse of the internal haemorrhoids through the anal verge4. Haemorrhoidal disease is the consequence of this pathological change. Although the causes are still unclear, certain predisposing and associated factors are identified.

Figure 1: Pathophysiology of Haemorroids

Repeated straining during constipation, diarrhoea or tenesmus, as well as spending long periods on the commode during defaecation may induce the freely mobile haemorrhoids to slide down into the anal canal. This may lead to trauma of the internal haemorrhoidal masses resulting in bleeding and later prolapse5 (protruding out of the anal verge). If the prolapse persists overtime, the continence function maybe impaired, resulting in mucoid discharge, pruritus, and fecal soiling. Other factors implicated in the causation of haemorrhoidal disease are heredity, absence of valves in the haemorrhoidal plexus and draining veins and portal hypertension.

Classification of Haemorrhoids

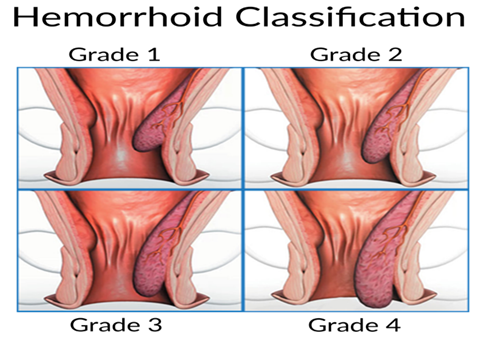

The haemorrhoids are classified according to their anatomical location as external and internal haemorrhoids.

The external haemorrhoids lie below and internal haemorrhoids above the dentate line. The external haemorrhoids are covered by squamous epithelium (very sensitive to pain sensation) and internal haemorrhoids are covered by transitional and columnar epithelium (less sensitive to pain).

Diagnosis

Haemorrhoidal disease can be diagnosed mainly from proper history taking. The commonest presentation of internal haemorrhoidal disease is bleeding (fresh blood) on defecation and protrusion of haemorrhoidal mass from anal verge.

The commonest presentation of external haemorrhoids is acute painful swelling in the perianal region. Other symptoms of haemorrhoidal disease are mucus discharge per rectum, pruritus ani, peri-anal soiling and severe anaemia (in patients with repeated bleeding episodes). Per rectal digital examination and proctoscopy is crucial in confirming the clinical diagnosis. It is vitally important to exclude colo-rectal pathology, before treating the patients as haemorrhoidal disease. Colo-rectal cancer may be missed in patients presenting with bleeding per rectum.

Grading of Internal Haemorrhoidal Disease

Grade I. Bleeding per rectum on defaecation.

Grade II. Protrusion of haemorrhoidal mass from anal verge on defaecation with spontaneous reduction.

Grade III. Protrusion of haemorrhoidal mass on defaecation and needs manual reduction.

Grade IV. Prolapse of haemorrhoidal mass which cannot be reduced.

Figure 2: Classification of Internal Hemorrhoids

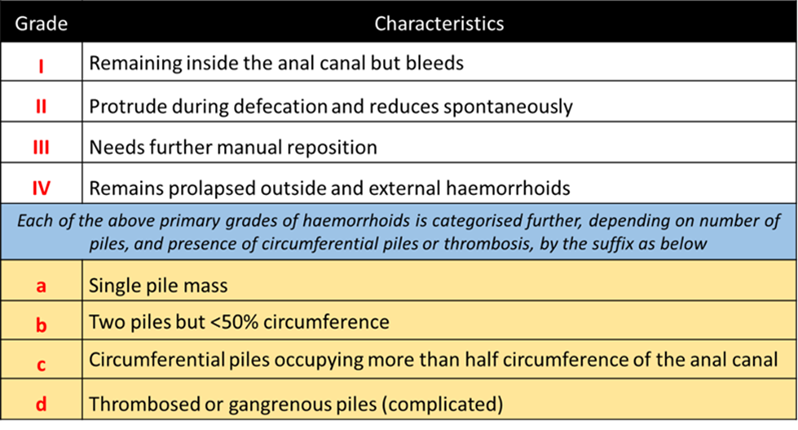

A new classification has been proposed by the Association of Surgeons of India, to further elaborate the clinical varieties of haemorrhoidal disease (Table 1).

Table 1: New classification of haemorrhoid

Treatment

Conservative treatment:

Dietary management and life-style modifications are effective in the treatment of grade I and some grade II patients6. The primary goal is to have adequate fluid and fibre intake to avoid straining at defaecation and consequently prevent bleeding. Stool softeners may also be used. Sitz baths in warm water are useful for anal hygiene and for relieving anal pain7, 8, and should be done 2 or 3 times a day.

Patients should be educated not to spend long periods of time reading on the toilet bowl. Symptoms may resolve sometimes by just simply changing the bowel habit. Many topical agents, suppositories and creams are available to alleviate pain, irritation and pruritus. Most are of marginal if any benefit. Oral venotonics, such as MPFF (micronized, purified, flavonoid, fraction) have been used in the treatment of haemorrhoidal disease. The rationale of flavornoids in haemorrhoidal disease is its unique mode of action and the mechanism of action on the sequence of changes in haemorrhoidal disease (as shown in the diagram).

1. Office Procedures

Patients not responding to conservative treatment, are candidates for minimally invasive procedures like rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, electro-coagulation, infra-red photo-coagulation, cryotherapy.

All these procedures are called office procedures, as they can be performed in a surgical out-patient department.

They are recommended for grades I, II and some grade III patients. These procedures should be offered to those not responding to conservative and medical therapy.

Rubber band ligation is the most common office procedure with acceptable outcome. It is the least expensive and cost-effective, simple technique of application of elastic band to the pedicle of haemorrhoids, using Baron’s gun and is most effective in patients with bleeding haemorrhoids. The banded haemorrhoidal mass becomes nacrotic and sloughs off within seven days. The main post-procedure problem is pain. It is usually due to technical fault. The band must be applied to the base (pedicle of haemorrhoids) above the dendate line (least sensitive area). All three haemorrhoidal masses should not be banded in one section to achieve maximum benefit with less postoperative complications.

Symptomatic relief after rubber band ligation is achieved in 65-85% of patients. Recurrence rate of 68% is seen after 4 to 5 years. These patients usually respond to repeat ligation9.

Sclero-therapy is conventional therapy practised in the olden days, but no longer practised now because of its serious complications. Injection was made into the submucosa, at the base of haemorrhoidal mass, using sclerosing agents. Ulceration, necrosis and infection may lead to severe sepsis resulting in portal pyaemia.

Monopolar (or) bipolar coagulation can be used in a form of electro-cautery., as an alternative to rubber band ligation. As the failure rate is high, it is not widely accepted.

Infrared-photocoagulation coagulates vessels and fixes the haemorrhoidal tissue. It is useful for grade I and some grade II patients. It is less painful, compared to rubber band ligation but necessitates more sessions and high recurrence rate in addition to high cost11, 12 so it is not widely used among colo-rectal surgeons.

Cryo-therapy is based on the concept that freezing at low temperature (using N2O (or) liquid nitrogen) can destroy the haemorrhoidal cushions. However, due to its high complication rate (such as irritation, pain, necrosis, delayed wound healing and risk of anal stenosis and incontinence) is no longer recommended.

2. Surgical treatment

Surgical haemorrhoidectomy is the treatment of choice for grade IV disease, strangulated haemorrhoids and grade III disease when minimal invasive procedures have failed. Only 5-10% of patients require surgery13. Surgical haemorrhoidectomy is considered the most effective treatment for haemorrhoidal disease with lower recurrences, but it is associated with more pain and postoperative disability compared to office procedures.

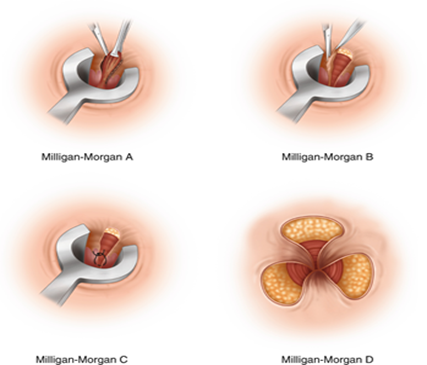

Open haemorrhoidectomy (Ligation and Excision)

L&E (Ligation and Excision) is called Milligan-Morgan Method (Figure 3). This is the gold standard up to now. The procedure is performed under general anesthesia or regional anesthesia with the patient in the lithotomy position. Each haemorrhoidal mass is excised from the underlying sphincter muscle and the pedicle is transfixed suture, tied. The wound is left open and healed by secondary union. The raw wound healed in four to eight weeks14, 15, 16.

Figure 3 : Milligan-Morgan Method

Closed haemorrhoidectomy

Closed haemorrhoidectomy is performed with the patient in the prone jack-knife position. The key to this technique is using the Fansler anal speculum (3cm in diameter and 7cm long) which allows excellent exposure of the entire haemorrhoidal tissue. The dissection of haemorrhoids is as in open operation, but the strip of excision should not be wider than 1.5 cm. The entire wound is closed with a running rapidly absorbable synthetic suture.

Both open and closed haemorrhoidectomy have been shown to be equally effective with no major differences in postoperative pain, hospital stay and complication, found in clinical trials17, 18, 19, 20. Closed method seems to promote faster wound healing.

Ligasure and Harmonic scalpel Haemorrhoidectomy

Ligasure21,22 and Harmonic scalpel23,24,25,26 have recently been evaluated for use in haemorrhoidectomy. Only Ligasure seems to offer some advantages.

However, the main limiting factor against using these instruments is their cost and lack of relevant studies.

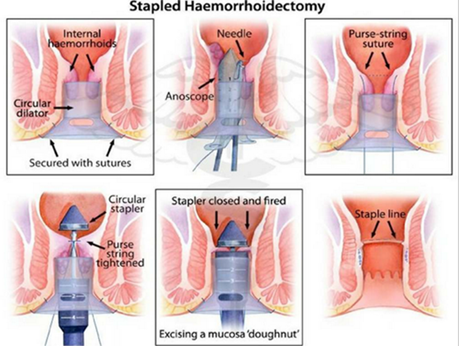

Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy

This is a relatively new technique developed to treat prolapsed haemorrhoids. It was popularized by Antonio Longo of the University of Palermo, Italy in 199827. In the literature, it is also known as: stapled haemorrhoidectomy, stapled anopexy, circumferential mucosectomy, rectal prolapsectomy, circular haemorrhoidectomy, circumferential stapled anoplasty and stapled rectal mucosectomy.

In 2001, an expert panel came up with the official term Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy28. With this procedure, prolapsing haemorrhoidal tissue is resuspended back into the anal canal. The haemorrhoids are not removed, but repositioned in their anatomic location. This is done with a 33 mm stapling gun which performs a circumferential resection of mucosa and sub-mucosa above the haemorrhoids and then, staples closed the defect13.

Stapled haemorrhoidopexy (Figure 4) is safe, effective, rapid and performed with minimal pain in most patients29, 30, 31. However, it requires proper training and experience in ano-rectal surgery and with circular stapling devices.

Severe postoperative complications have been reported in the literature including bleeding, persistent pain, anal sphincter injuries, rectal perforation, retroperitoneal sepsis, ano-vaginal fistula and pelvic sepsis. Bleeding from stapling site is quite common (usually requires additional stitches). RCT trials are necessary for establishing the cost-effectiveness and long-term efficacy of stapled haemorrhoidopexy. The technique is not universally adopted by surgeons world-wide.

Figure 4: Steps of stapled haemorrhoidopexy

Doppler-Guided Haemorrhoidal Artery Ligation (DGHAL)

This procedure is performed using a specially designed proctoscope (Moricorn) housing a Doppler transducer that can identify haemorrhoidal arteries and permit their ligation with sutures32.

DGHAL is a relatively painless method of treating haemorrhoidal disease with low morbidity and a reported success rate as high as 90% for grade III disease32,33,34,35,36.

In our surgical practice in Myanmar, we have no experience of DGHAL, so far as the instrument (device) is not available.

According to the multi-center randomized study of the liga Longo Trial on the comparison of surgical devices for grade II and III disease, the finding suggest that device type has little impact on haemorrhoidal treatment results. Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation and stapled haemorrhoidopexy were done on three hundred and seventy seven patients, allocated randomly into two groups. No statistical difference was found between the two groups in terms of recurrence or re-operation37.

Other Types of Haemorrhoidectomy

Laser haemorrhoidectomy is performed using Nd:YAG laser or CO2 laser. To date, it does not seem to offer any significant advantage compared to other approaches and the equipment is expensive38.

White head haemorrhoidectomy is performed by excision of the submucosal and subdermal haemorrhoidal plexuses circumferentially at the dentate line. The main indication of white head procedure is for extensive circumferential haemorrhoides. However, severe late complications such as stenosis and ectropion have been reported39.

Early Postoperative problems

Early post-operative problems tend to be more common after surgical haemorrhoidectomy. They can be summarized as: pain, urinary retention, postoperative bleeding, urinary tract infection and rarely, retroperitoneal sepsis.

Late Postoperative problems

Anal stricture and fecal and flatus incontinence are the most distressing problems following haemorrhoidal surgery.

The outcome of corrective treatment is very poor and options are few. The best solution to this problem is to avoid surgery as much as possible and to follow the guidelines and algorithms (Figure 5) according to the grade and stage of the disease.

Figure 5: Algorithm of treatment of hemorrhoidal disease

References

- Haas, PA; Haas, GP; Schmaltz, S; Fox, TA Jr. The prevalence of haemorrhoids. Dis.Colon Rectum

1983;26:435-9. - Thompson, WH. The nature of haemorrhoids. Br.J.Surg., 1975;62,542-52.

- Johanson, JF; Sonnenberg, A. Temporal changes in the occurrence of haemorrhoids in the United States and England. Dis. Colon Rectum, 1991; 34,585-91.

- Hass, PA; Fox, TA; Haas, GP. The pathogenesis of haemorrhoids. Dis. Colon irabayashiRectum.1984;27;442-450.

- Loder, PB; Kamm,MA; Nicholls, RJ; Phillips, RK. Haemorrhoids: pathology, pathophysiology andaetiology. Br. J. Surg., 1994;81, 946-54.

- Alonso-Coello, P; Guyatt, G; Heels-Ansdell,D; Johanson, JF;Lopez- Yarto,M;Mills, E;Zhou, Q. Laxatives for the treatment of haemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev, 2005 Oct. 19;(4): CD 004649.

- Dodi,G; Bogoni, F; Infantino,A;Pianon,P; Mortellaro, LM; Lise, M. Hot or cold in anal pain ? A study of changes of internal anal sphincter pressure profiles. Dis. Colon Rectum, 1986;29, 248-51.

- Shafik,A. Role of warm water bath in ano-rectal conditions. The “ thermo-sphincteric reflex” J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1992;16, 304-8.

- Madoff, RD; Fleshman, JW. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the diagnosis and treatment of haemorrhoids. Gastroenterology, 2004; 126, 1463-73.

- Randall, GM; Jensen, DM; Machicado, GA; irabayashi, K; Jensen,ME; You, S; Pelayo, E. Prospective randomized comparative study of bipolar versus direct current coagulation for treatment of bleeding internal haemorrhoids. Gastrointest. Endosc., 1994;40, 403-10.

- Dennison, A; Whiston, RJ; Rooney, S; Chadderton,RD; Wherry, DC; Mooris,DL. A randomized comparison of Infrared photo-coagulation with bipolar diathermy for the outpatient treatment of haemorrhoids.: Dis. Colon Rectum, 1990;33, 32-4.

- Johanson, JF; Rimm, A. Optimal non-surgical treatment of haemorrhoids: a comparative analysis of infrared coagulation, rubberband ligation and injection sclerotherapy. Am. J. Gastroenerol., 1992; 87, 1600-6.

- Morin,N. American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons ( ASCRS ) . 2008 core subjects: Haemorrhoids and Fissure in Ano. Available from : URL: http://w.w.w.facrs. Org/physicians/ education/core subjects/2008/ haemorrhoids_ fissure_ in_ ano/

- Milligan, ETC; Morgan, CN; Jones,LE; Officer, R. Surgical anatomy of the anal canal and the operative treatment of haemorrhoids. Lancet, 1937; 2, 119-24.

- Andrews, BT; Layer, GT; Jackson,BT; Nicolls, RJ. Randomized trial comparing diathermy haemorrhoidectomy with the scissor dissection Milligan- Morgan operation. Dis. Colon Rectum, 1993; 36, 580-3.

- Seow- Choen, F; Ho, withoutYH; Ang, HG; Goh, HS. Prospective, randomized trial comparing Randomized trialpain and clinical function after conventional scissor excision/ ligation versus diathermy excision without ligation for symptomatic prolapsed haemorrhoids. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1992; 35, 1165-9.

- Ho, YH; Seow- Choen, F; Tan, M; Leong, AF. Randomized controlled trial of open and closed haemorrhoidectomy. Br. J. Surg., 1997; 84, 1729- 30.

- Carapeti, EA; Kamm, MA; Mc Donald, PJ; Chadwick, SJ; Phillips, RK. Randomized trial ofopen versus closed day-case haemorrhoidectomy. Br. J. Surg., 1999; 86, 612- 3

- Arbman, G; Krook, H; Haapaniemi, S. Closed vs open haemorrhoidectomy_ is there any difference? Dis. Colon Rectum, 2000; 43, 31- 4.

- Gecomanoglu, R Sad O; Koc,D; Inceorlu,R. Haemorrhoidectomy : open or closed technique ? A prospective randomized clinical trial. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2002; 45, 70- 5.

- Palazzo, FE; Francis, DL; Clifton, MA. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasurevs open haemorrhoidectomy. Br. J. Surg., 2002; 45, 70- 5.

- Jayne, DG; Botterill, I; Ambrose, NS; Brennan, TG; Guillou, PJ; O’Riordain, DS. Randomized clinical trial of Ligasurevs conventional diathermy forday-case haemorrhoidectomy. Br. J. Surg., 2002; 89, 428- 32.

- Khan, S; Pawlak, SE; Eggenberger, JC; Lee, CS; Szilagy, EJ; Wu, JS; Margolin, MD DA. Surgical treatment ofhaemorrhoids : prospective, randomized trial comparing closed excisional haemorrhoidectomy and the Harmonic Scalpel techniqectomyue of excisional haemorrhoidectomy. Dis. Colon Rectum; 2001; 44, 845- 9.

- Tan, JJ; Seow- Choen, F. Prospective, randomized trial comparing diathermy and Harmonic scalpel haemorrhoidectomy, a prospective evaluation. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2001;44, 677- 79.

- Armstrong, DN; Ambroze, WL; Schertzer, ME; Orangio, GR. Harmonic Scalpel vsElectrocauteryhaemorrhoidectomy , a prospective evaluation. Dis. C olon Rectum, 2001; 44, 558- 64.

- Chung, CC; Ha, JP; Tai, YP; Tsang, WW; Li, MK. Double-blind, randomized trial comparing Harmonic Scalpel haemorrhoidectomy, bipolar scissors excision: ligation technique. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2002; 45, 789- 94.

- Longo, A . Treatment of haemorrhoidal disease by reduction of mucosa and haemorrhoidal prolapse with a circular suturing device : a new procedure. Proceding of the 6th World congress of endoscopic surgery, Rome, 1998, 777- 84.

- Corman, ML; Gravie, JF;i Hager, T; London, MA; Mascagni, D; Nystrom, PO; Seow- Choen, F; Abcarian, H; Marcello, P; Weiss, E; Longo, A. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy : a consensus position paper by an international working party- indication, contra-indications and technique. Colo-rectal Dis., 2003; 5, 304- 10.

- Singer, MA; Cintron, JR; Fleshman, JW; Chaudhry, V; Birnbaum, EH; Read, TE; Spitz, JS; Abcarian, H. Early experience with stapled haemorrhoidectomy in the United States. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2002; 45, 360- 7.

- Arnaud, JP; Pessaux, P; Huten, N; De Manzini, N; Tuech, JJ; Laurent, B; Simone,M. Treatment of haemorrhoids with circular staple, a new alternative to conventional methods : a prospective study of 140 patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg., 2001; 193, 161- 5

- Habr- Gama, A; e Sous, AH Jr; Rovelo, JM; Souza, JV; Benicio, F; Regadas, FS; Wainstein, C; da Cunha, TM; Marques, CF; Bonardi, R; Ramos, JR; Pandini, LC; Kiss, D. Stapled haemorrhoidectomy : initial experience of a Latin American group. J. Gastrointest. Surg., 2003; 7, 809-13.

- Morinaga, K; Hasuda, K; Ikeda,T. A novel therapy for internal haemorrhoids : ligation of the haemorrhoidal artery with a newly devised instrument ( Morico ) in conjunction with a , doppler flow-meter. Am. J. Gastroenterol., 1995; 90, 610- 3.

- Sohn, N; Aronoff, JS; Cohan, FS; Weinstein, MA. Transanalhaemorrhoidal de arterialization is an alternative to operative haemorrhoidectomy. Am. J. Surg., 2001; 182, 515- 9.

- Ramirez, JM; Aguilella, V; Elia, M; Gracia, JA; Martinez, M. Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation in the management of symptomatic haemorrhoids. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig., 2005; 97 – 103.

- Felice , G; Privitera, A; Ellul, E; Klaumann, M. Doppler guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation : An alternative to haemorrhoidectomy. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2005; 48, 2090- 3.

- Greenberg, R; Karin, E; Avital, S; Skornick, Y; Werbin, N. First 100 cases with Doppler guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation. Dis. Colon Rectum, 2006; 49, 485- 9.

- AurelienVenara, JulliettePodevin, Philippe Godeberg, Yann Redon, Marie- Line Barussand, Igor Sielezneff, Michel Queralto, Cecile Bourbao, Anna Chiffoleau, Paul A Lehur, on behalf of the Liga Longo group. A comparison of surgical device for grade II and grade III haemorrhoidal disease. Results from the Liga Longo Trial comparing trans anal Doppler guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation with mucopexy and circular stapled haemorrhoidopexy. International Journ. ofColo-rectal disease, 2018; 33, 1479- 83.

- Wang, JY; Chang-Chieu, CR; Chen, JS; Lai, CR; Tang, RP. The role of lasers in haemorrhoidectomy. Dis. Colon Rectum, 1991; 34, 78- 82.

- Wolff, BG; Culp, CE. The whitehead heamorrhoidectomy. An unjustly maligned procedure. Dis. Colon Rectum , 1988; 31, 587- 90.

Author Information

Win Myint

Clinical Excellence Patron, Pun Hlaing International Hospital

Former Head of Department of Surgery, IM 2 and IMM