Oncology Emergency: Neutropenic Sepsis

Introduction

Febrile neutropenia is one of the most common complications in patients who are receiving systemic anticancer treatment; incidence being 5–10% of those with solid tumors 1, 85–95% in acute leukemia, and 20–25% of other hematologic malignancies 2,3. Different levels of neutropenia risks occur in various chemotherapy regimens20 .The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) of the UK analyzed official death statistics which demonstrates a doubling of the annual mortality rate due to neutropenic sepsis between 2001 and 2010, with a peak of 700 deaths in 20107. It is widely acknowledged that neutropenic fever can rapid level up major life-threatening complications which means that it is classified as an oncological emergency 8, 9 with an associated mortality rate ranging from 2% to 21% 4–6.

Immunocompromised conditions are related with lower sepsis survival. Therefore, it is imperative that patients with suspected neutropenic sepsis must be assessed and treated immediately with broad spectrum antibiotics within one hour of patient arrival to comply with the National Chemotherapy Advisory Group 2009 standard which is ‘door to needle time’ is less than an hour.

Definitions

Febrile neutropenia is defined as a temperature of >38®C on two separate measurements at least 1 hour apart within 12 hours or a single fever spike of >38.5®C. Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of ≤ 0.5 x 109/L or combination of ≤1.0 x 109/L with a predicted decrease to 0.5 x 109/l over next 48 hours 7, 13. There is high risk of infection and bacteremia leading to critical illness with sepsis in patients with severe neutropenia (ANC<0.5 x 109/L) and in those with prolonged neutropenia longer than 7 days.

Neutropenic sepsis is suspected for any cancer patient who present within 30 days of chemotherapy with:

- Febrile neutropenia

- Hemodynamically unstable associated with sepsis regardless of temperature with SBP <90 mmHg, DBP <60 mmHg or MAP (mean arterial pressure) <65 mmHg, tachycardia – HR>100, confusion/agitation

- An acute respiratory distress syndrome with hypoxia, tachypnea and requirement of oxygen supplement or bilateral infiltrative changes diffusely on Chest X-ray

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation and/or multiple organ failure

Risks

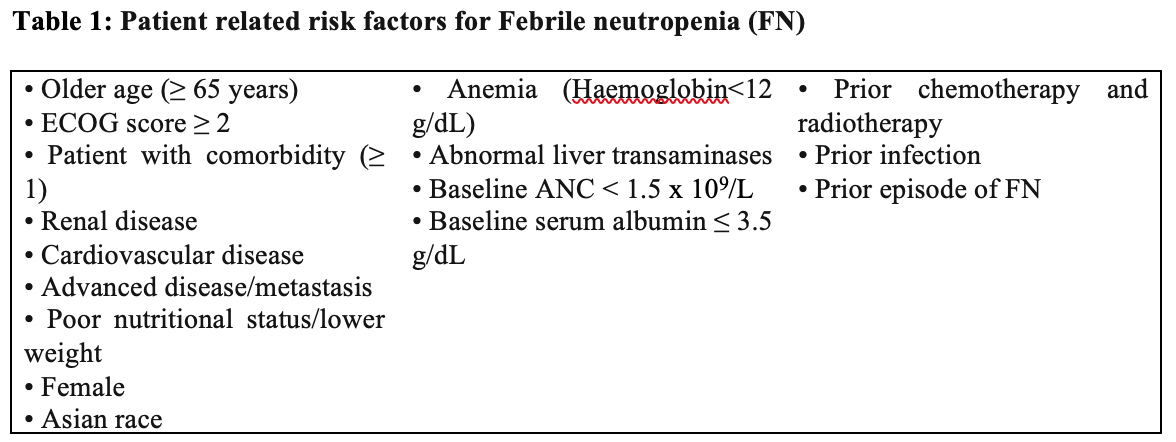

Consensuses from different areas over the world propose that the overall risk of febrile neutropenia should be taken into consideration in both chemotherapy regimens and patient characteristics 10.

In addition to patient related risks, chemotherapy regime is considered as important risk factor for neutropenic fever10. An incidence of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia more than 20% is categorized as high risk while those of 10-20% an intermediate risk, those of lower than 10% is considered as a low risk 10, 20-23.

The following chemotherapy regimens are high risk of FN (>20%)10, 20:

- Breast cancer – AC/Docetaxel (Cyclophosphamide/Adriamycin), TAC (Docetaxel/Epirubicin/Cyclophosphamide) TCH (Docetaxel/carboplatin/trastuzumab)

- Lungs cancer – ACE(Etoposide/Epirubicin/Cyclophosphamide), CAV (Vincristine/Etoposide/Epirubicin), ICE (Ifosfamide/Epirubicin/Cyclophosphamide), VICE(Ifosfamide/Carboplatin/Etoposide/Vincristine), Docetaxel/Carboplatin

- UGI/Colorectal cancer – FLOT (5FU/Leucovorin/Oxaliplatin/Docetaxel), DCF ( Docetaxel/cisplatin/5FU), TCF(Taxol/cisplatin/5FU), ECF(Epirubicin/cisplatin/5FU) EOF (Epirubicin/oxaliplatin/5FU), EOX (Epirubicin/ Oxaliplatin/Capecitabine), ECX(Cisplatin/Capecitabine/Epirubicin)

- Germ cell cancer – VIP (Etoposide/Ifosfamide/Cisplatin)

- Sarcoma – MAID (Mesner/Doxorubicin/Ifosfamide/ Dacarbazine)

- Lymphoma – DHAP (Cisplatin/Cytarabine/Dexamethasone), ESAP (Cytarabine/Etoposide/6-mercaptopurine/cisplatin), ABVD (Doxorubicin/Bleomycin/Vinblastine/Dacarbazine), BEACOPP (Etoposide/Doxorubicin/Cyclophosphamide/Vincristine/Bleomycin/Prednisone/Procarbazin), EPOCH (Etoposide/ Vincristine/Cyclophosphamide/Doxorubicin/Prednisone), StanfordV (Doxorubicin/Vincristine/ Nitrogenmustard/Vinblastine/Bleomycin/Etoposide/Prednisone), IGEV (Isophosphoramide/Gemcitabine/Vinorelbine/Prednisolone)

Mortality

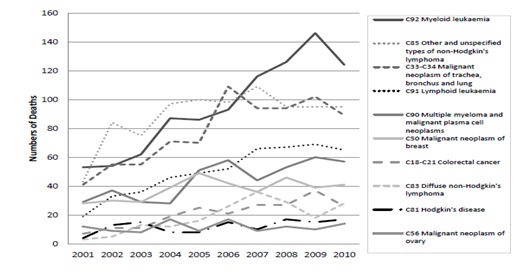

The ten commonest tumor sites where death involved neutropenic sepsis are shown in the following graph 7 over the period from 2001 to 2010.

Figure 1: Absolute numbers of cancer deaths from neutropenic sepsis by diagnosis, (pediatric and adult) England and Wales 2001-2010.

Assessment and Investigations

Patients with suspected neutropenic sepsis must be assessed promptly with thorough history taking and full physical examination on arrival at hospital. The clinical parameters including in Early Warning Scoring (EWS) must be recorded: respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, blood pressure and level of consciousness or new onset confusion. EWS and early involvement of intensive care team is highly recommended to improve mortality15.

Since patients receiving chemotherapy/immunosuppressive treatment are categorized as high risk group for sepsis, it is mandatory to complete Sepsis 6 Care Bundle in the NHS. The following actions are included in Sepsis 6 Care Bundle 13, 14:

- To maintain O2 saturation >95% or 88-92% in those with known CO2 retaining

- Blood culture before administration of antibiotics (however, antibiotics should not be delayed more than an hour)

- Lactate measurement by VBG

- Appropriate IV Antibiotics

- Fluid resuscitation

- Fluid balance chart to measure hourly urine output and consider for urinary catheterization

Other recommended blood tests are full blood count (FBC), renal function, urea and electrolytes, liver functions, bone profile and C-reactive protein (CRP). Infection screening must be done for finding the source of infection to optimize the antibiotics accordingly. Infection screen tests include blood culture as above in sepsis 6 bundle, MRSA screen (multiple sites), mid-stream urine culture, culture of any obvious source of infection (for instance, wounds or ulcers, line sites, stool culture if complained of diarrhea to look for C. diff toxin and norovirus , sputum) and respiratory viral screening. Sepsis screening has been associated with decreased mortality 14.

Risk assessment at outpatient setting for clinically stable patients

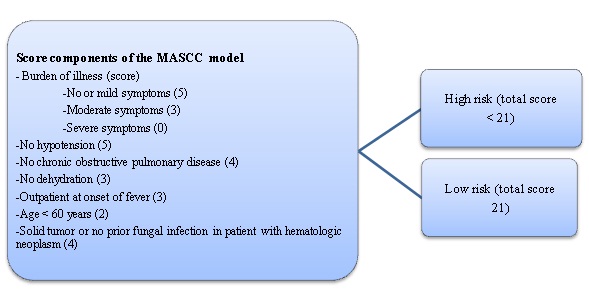

The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) score is used for risk stratification of outpatients with febrile neutropenia. A maximum score is 26 and the cutoff value for high risk is 21. Higher scores indicate lower risk. ≥ 21 score reveals that patients are at low risk from those with high risk (< 21 points) for major life threatening febrile neutropenia related complications 11, 12. Those low risk category groups may be managed with oral antibiotics as outpatient setting 16-19eg. by 5-7 day course of oral Co-amoxiclav 625mg TDS with Ciprofloxacin 500mg BD. For Penicillin allergic patients, alternative suggested antibiotics would be PO Doxycycline/Clindamycin 7, 13, 16-19. However, it is important to give advice to patients to seek urgent medical attention or presenting to hospital if unwell. Patient needs to monitor temperature for 3 days anytime or when they feel unwell at home.

MASCC risk index is calculated by using the following variables 11, 12, 13:

- Burden of illness

- Blood pressure

- Presence or absence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Solid tumor or hematological malignancy with or without a history of previous fungal infection

- Dehydration

- Inpatient or outpatient status at the time of onset of neutropenic fever

- Age

Figure 2: The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) scoring system. The components of the MASCC have a maximum score of 26 (5 + 5 + 4 + 4 + 3 + 3 +2). Patients with scores ≥ 21 are at low risk for complications, while patients with scores < 21are at high risk for complications 11.

Treatment

Since local microbiology guidelines may differ according to local microbial resistances and pattern, microbiologist advice is always recommended.

In the NHS, initial empiric intravenous antibiotics by Piperacillin/Tazobactam 4.5g TDS should be administered immediately within the national mandatory standard of one hour door-to-needle time. Intravenous Gentamicin should be considered to add if the patient is clinically unwell or hypotensive. Once Gentamicin is initiated, drug monitoring according to BNF guideline/local antimicrobial guideline is highly recommended. Gentamicin should not be used for patients with known previous hearing impairment and those who are blind. Meropenem is recommended to use in such patients as alternative instead of adding Gentamicin.

For penicillin allergic patients (with history of having only widespread rash), Meropenem can be substituted. However, those who has severe allergy (anaphylaxis, angioedema, Stevens-Johnson, syndrome), Gentamicin and Vancomycin are recommended and it should be considered to add Metronidazole if abdominal sepsis is suspected.

After 48 hours of treatment, intravenous antibiotics is considered to switch to oral antibiotic in patients whose risk of developing septic complications has been reassessed as low by using a validated risk scoring system and clinical status 7, 13.

Antibiotics should be updated if blood culture/other cultures are positive according to sensitivity or microbiologist advice.

For patients who are currently or previously MRSA positive or those with skin or soft tissue involvement, Vancomycin is recommended.

Antifungal should be considered if there is no improvement clinically with standard antibiotics or those with high risk for invasive fungal infections such as diabetes mellitus, chronic liver failure, chronic renal failure, prolonged invasive vascular devices (hemodialysis catheters, central venous catheters), total parenteral nutrition, recent major surgery (particularly abdominal), prolonged administration of broad spectrum antibiotics recently, recent prolonged hospital/ICU admission, recent fungal infection, severe skin and soft tissue infections, and multisite fungal colonization1, 7, 13.

If Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is concerned (for instance, in transplant patients),it should be considered to give co-trimoxazole and Pneumocystis PCR testing on BAL sample or induced sputum should be arranged for microbiological diagnosis.

Adding granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF) should be considered if the patient is shocked or if febrile neutropenia is complicated such as multi-organ involvement/colitis, or the duration of neutropenia is likely to be prolonged 7, 13.

Patients in the category of high FN risk (≥ 20%) should be recommended for prophylactic use of G-CSF 10, 20-23.

Lastly, in terms of prophylactic antibiotics according to NICE guideline, for patients with acute leukemia, stem cell transplants or solid tumors with significant neutropenia (neutrophil count 0.5 x 109/L or lower) anticipated due to consequence of chemotherapy, offer prophylaxis with a fluoroquinolone during the expected the period of neutropenia only 7.

Conclusion

To conclude, neutropenic sepsis is a potentially life-threatening complication requiring immediate evaluation and empirical treatment with broad spectrum antibiotics in timely manner within one hour of arrival at hospital. A EWS system and early ICU team input can improve mortality. MASCC is a useful tool for assessing risk stratification of neutropenic patients.

References

- Azoulay E, Mokart D, Pène F, Lambert J, Kouatchet A, Mayaux J, Vincent F, Nyunga M, Bruneel F, Laisne LM, Rabbat A, Lebert C, Perez P, Chaize M, Renault A, Meert AP, Benoit D, Hamidfar R, Jourdain M, Darmon M, Schlemmer B, Chevret S, Lemiale V (2013) “Outcomes of critically ill patients with hematologic malignancies: prospective” multicenter data from France and Belgium–a groupe de rechercherespiratoireenréanimationonco-hématologique study. J ClinOncol 31:2810–2818. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.47.2365

- Soares M, Bozza FA, Azevedo LCP, Silva UVA, Corrêa TD, Colombari F, Torelly AP, Varaschin P, Viana WN, Knibel MF, Damasceno M, Espinoza R, Ferez M, Silveira JG, Lobo SA, Moraes APP, Lima RA, de Carvalho AGR, do Brasil PEAA, Kahn JM, Angus DC, Salluh JIF (2016) “Effects of organizational characteristics on outcomes and resource use in patients with cancer admitted to intensive care units.” J ClinOncol 34:3315–3324. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9549

- Matthias Kochanek1,2 & E. Schalk2,3 & M. von Bergwelt-Baildon2,4 & G. Beutel2,5 & D. Buchheidt2,6 & M. Hentrich7 & L. Henze2,8 & M. Kiehl2,9 & T. Liebregts2,10 & M. von Lilienfeld-Toal11 & A. Classen1 & S. Mellinghoff1 & O. Penack12 & C. Piepel13 & B. Böll1,2 Received: 8 October 2018 / Published online: 22 February 2019, Annals of Hematology (2019) 98:1051–1069, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-019-03622-0

- Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB et al.(2009) “Prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy”. Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD007107.

- Smith TJ, Khatcheressian J, Lyman GH et al. (2006) “Update of recommendations for the use of white blood cell growth factors: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline”. J ClinOncol;24:3187–205.

- Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J et al. (2006) “Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia” in adult cancer patients. Cancer;106:2258–66.

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence and the National Collaborating Centre for Cancer. (2012) “Neutropenic sepsis: prevention and management of neutropenic sepsis in cancer patients.” Cardiff: NCC-C,www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13905/60864/60864.pdf [Accessed 28 February 2013]

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM etal.(2008) “Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock”. Crit Care Med 2008;36:296–327.

- Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA et al. .(2010) Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department.” Crit Care Med;38:1045–53.

- Committee of Neoplastic Supportive-Care (CONS), China Anti-Cancer Association, Committee of Clinical Chemotherapy, China Anti-Cancer Association (2020). “Current management of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in adults: key points and new challenges” Cancer Biol Med 2020. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-394.0069

- Klastersky J, PaesmansM, Rubenstein EB, Boyer M, Elting L, Feld R,Gallagher J, Herrstedt J, Rapoport B, Rolston K, Talcott J, for the Study Section on Infections of Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (2000) “The Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk index: a multinational scoring system for identifying low-risk febrile neutropenic cancer patients”. JCO. 18(16):3038–3051. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.16.3038

- Use of MASCC score in the inpatient management of febrile neutropenia: a single-center retrospective study Prarthna V. Bhardwaj1 & Megan Emmich2 & Alexander Knee3 & Fatima Ali4 &Ritika Walia5 & Prithwijit Roychowdhury6 & Jackson Clark4 &Arthi Sridhar7 & Tara Lagu8,&KahPoh Loh”(2021) Supportive Care in Cancer 29:5905–5914, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06154-4

13. Cambridge University NHS foundation trust local guideline for Neutropenic sepsis

14. Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, Townsend SR, Schorr CA, Beale R, Osborn T, Lemeshow S, Chiche JD, Artigas A, Dellinger RP (2014) “Surviving sepsis campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study”.

Intensive Care Med 40:1623–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3496-0

15. Bokhari SWI, Munir T, Memon S et al (2009) “Impact of critical care reconfiguration and track-and-trigger outreach team intervention on outcomes of haematology patients requiring intensive care admission.”Ann Hematol 89:505–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-009-0853-0

16. Taj M, Nadeem M, Maqsood S, Shah T, Farzana T, Shamsi TS (2017) “Validation ofMASCC score for risk stratification in patients of hematological disorders with febrile neutropenia”. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 33(3):355–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12288-016-0730-7

17. Gunderson CC, Erickson Britt K, Wilkinson-Ryan I et al (2019) “Prospective evaluation of Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer risk index score for gynecologic oncology patients with febrile neutropenia.” Am J ClinOncol 42(2):138–142.https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000498

18. Baskaran ND, Gan GG, Adeeba K (2008) “Applying the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer risk scoring in predicting outcome of febrile neutropenia patients in a cohort of patients.” Ann Hematol 87(7):563–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-008-0487-7

19. Cherif H, Johansson E, Björkholm M, Kalin M (2006) “The feasibility of early hospital discharge with oral antimicrobial therapy in low risk patients with febrile neutropenia following chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies”. Haematologica. 91(2):215–222

20. Rapoport BL, Aapro M, Paesmans M, van Eeden R, Smit T,Krendyukov A, et al.(2018) “Febrile neutropenia (FN) occurrence outsideof clinical trials: occurrence and predictive factors in adult patientstreated with chemotherapy and an expected moderate FN risk.Rationale and design of a real-world prospective, observational,multinational study”.BMC Cancer.; 18: 917.

21. Aapro MS, Bohlius J, Cameron DA, Dal Lago L, Donnelly JP,Kearney N, et al. (2010) “update of EORTC guidelines for the use ofgranulocyte-colony stimulating factor to reduce the incidence ofchemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia in adult patients withlymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumours.” Eur J Cancer.2011; 47: 8-32.

22. Lyman GH, Poniewierski MS. (2017) “A patient risk model of chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia”: lessons learned from the ANC Study Group. J Natl ComprCancNetw.2017; 15:1543-50.

23. Kosaka Y, Rai Y, Masuda N, Takano T, Saeki T, Nakamura S,et al.(2015) “Phase iii placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomizedtrial of pegfilgrastim to reduce the risk of febrile neutropeniain breast cancer patients receiving docetaxel/cyclophosphamide chemotherapy”. Support Care Cancer; 23: 1137-43.

Author Information

Su Lei Yin

M.B., B.S, MRCP (UK), M.Sc Oncology (The University of Nottingham)

Specialty Trainee Registrar in Medical Oncology at Department of Oncology,

Cambridge University Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust,

Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK